This review of Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat by Hito Steyerl appears in the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

During the second half of the 20th century the favoured metaphor for the effortless and detached exercise of power was ‘the push of a button’. It linked everyone from ordinary citizens through to the leaders of nations, for whom this same gesture could activate anything from an ice maker to nuclear war. After the millennium, the metaphor shifted, as innovation replaced many buttons with just one: the click of a mouse, which became the marker of everything from winning an online auction to raining fire on insurgents from an air-force base a thousand miles away. Now, in the incipient age of AI, a shift is underway, and the metaphor will have to shift too. ChatGPT and its siblings are intent on removing the button and the mouse to create a world in which a mere articulated thought will accomplish their work and ours – driving cars, killing enemies, making art. And so mastery shrinks from a push to a click to a wish. Which new metaphor will win is not yet clear, but I would put money on the one cited by Hito Steyerl in the opening pages of Medium Hot: fire and forget.

While Medium Hot does not trail its interest in AI on the cover (its title is a nod to Marshall McLuhan’s designation of television as a ‘cool medium’), AI is its central subject and its substance a sustained argument against both the firing and the forgetting. At its heart is the question of what lies behind the AI-generated images that seem to be taking over the visual realm and how all that relates to a world in which ‘heat’ of one kind or another is increasing continuously. They emerge at a time of heat in every sense of the word: ‘an era of widespread multi-crisis – with regular financial breakdowns […], post-pandemic recessions, accelerating climate change and increasing extreme weather events, rising right-wing and neofascist movements globally’ as well as active conflicts in ‘Yemen, Ukraine, Tigray, Gaza, Sudan and Congo’. The more ‘machine “autonomy”’ we get, ‘the more entangled and messed up the world seems to be [and] almost everything impacts everything else’. However benign the enterprise of image-generation might seem, it results in objects whose very creation involves ‘wrecking their surroundings through the extraction of labour, data and resources, rendering warfare, marketing and surveillance as variations on the same spectrum’. Each one creates ‘some kind of damage or partial destruction of reality’. What sceptics like to term ‘AI slop’ might better be termed AI toxic waste.

While Medium Hot does not trail its interest in AI on the cover (its title is a nod to Marshall McLuhan’s designation of television as a ‘cool medium’), AI is its central subject and its substance a sustained argument against both the firing and the forgetting. At its heart is the question of what lies behind the AI-generated images that seem to be taking over the visual realm and how all that relates to a world in which ‘heat’ of one kind or another is increasing continuously. They emerge at a time of heat in every sense of the word: ‘an era of widespread multi-crisis – with regular financial breakdowns […], post-pandemic recessions, accelerating climate change and increasing extreme weather events, rising right-wing and neofascist movements globally’ as well as active conflicts in ‘Yemen, Ukraine, Tigray, Gaza, Sudan and Congo’. The more ‘machine “autonomy”’ we get, ‘the more entangled and messed up the world seems to be [and] almost everything impacts everything else’. However benign the enterprise of image-generation might seem, it results in objects whose very creation involves ‘wrecking their surroundings through the extraction of labour, data and resources, rendering warfare, marketing and surveillance as variations on the same spectrum’. Each one creates ‘some kind of damage or partial destruction of reality’. What sceptics like to term ‘AI slop’ might better be termed AI toxic waste.

How and why such such waste is produced is another question, and readers familiar with Steyerl’s work as an artist, film-maker and writer will know better than to expect straightforward answers. Medium Hot steers clear of the ‘normativity and structural conformism’ of standard academic writing, in part because it is so ‘easily reproducible’ by systems such as ChatGPT and in part because that is just not how Steyerl’s brain functions. In a mode reminiscent of her work in films such as November (2004) and Liquidity Inc. (2014), the ten essays in here make use of both journalistic investigation and theory, but they are powered too by wilder modes of fantasy and juxtaposition. That they are capped off with an engagingly surreal ‘collaboration’ with the AI program GPT-3 makes total sense, in context.

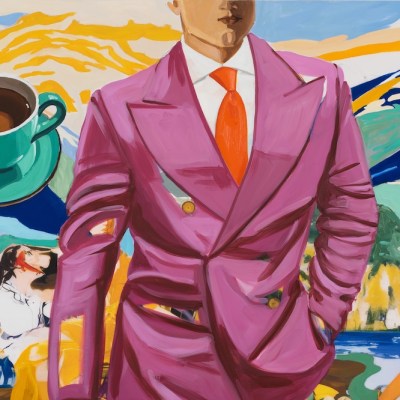

Image of Hito Steyerl (2025), a ‘portrait’ of the author generated by the AI model Stable Diffusion. Couertesy Hito Steyerl

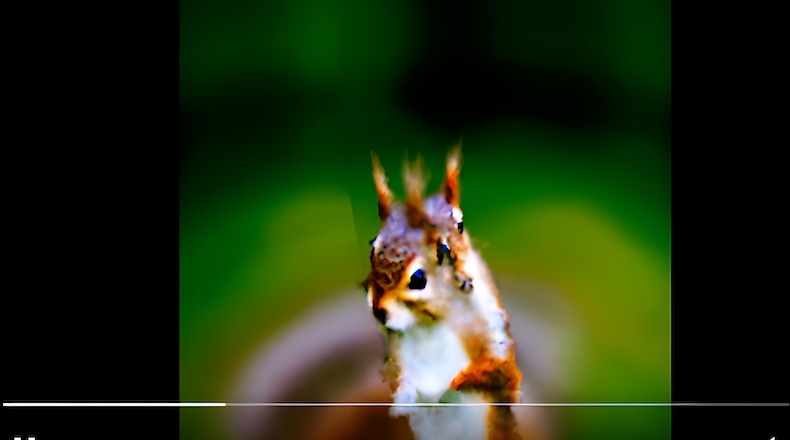

Thus, the ‘Janus Problem’, in which additional ghostly faces appear in the results of certain image-generators leads her on to the real-world phenomenon of ‘ghost workers’ – also called ‘microworkers’ – who help to train AI models. These include Syrian refugees in Germany employed to filter images of their own destroyed home towns ‘deemed too violent for social media consumers’ but not too violent for the very people forced into exile by that same destruction. The mass collection of data from such microworkers builds systems that produce images as if by ‘unmediated magic’, when in fact their source is ‘massive exploitation and expropriation at the level of production’. Perhaps then, Steyerl suggests, the ‘ghostly emanations’ of the Janus Problem are ‘in fact portraits of the hidden microworkers, haunting and pervading’ the outputs.

The essays here are as insightful as they are dense, and no less convincing for their forays into wild reasoning. They are also, as Steyerl fans will expect, memorably stylish, above all in delivering a damning verdict. By three essays in, I had lost count of the sections I had underlined for quoting. ‘In the absence of a killer app, the [AI] industry tries to fall back on the original killer apps – weapons’; statistical renderings such as the unflattering portrait of Steyerl produced by the AI image-generator Stable Diffusion are ‘mean images’ in the widest sense of the phrase; the smoothed, misshapen, truncated and elongated human bodies produced by Stable Diffusion 3 are ‘knuckleporn’. It is, indeed, hard to imagine ChatGPT mimicking her with any success.

While some of the ground covered here will be familiar to those already following developments in AI, Medium Hot is a brilliant salvo against exploitative blandness and the damage it depends on to exist. Steyerl’s approach is, of course, anything but fire and forget: as she notes, all descriptions at this stage are preliminary and her work is far from done. If she is right that we are on track for a future in which ‘any decision is automated and determined by some sort of elite eugenicism, military-purpose AGI, cryptosovereigns and reality TV extinction spectacles’, at least readers of Medium Hot will know what is happening to them.

Image of a squirrel generated by the text-to-3D tool DreamFusion in 2022, which demonstrates the Janus Problem, posted on X (then Twitter) by @_akhaliq. Courtesy Hito Steyerl

Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat by Hito Steyerl is published by Verso.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.