From the June 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Have you been to the 1950s public lavatories in Hay-on-Wye? Next time you are there you can ignore the second-hand bookshops and head straight for them. The advice comes from one of the more outré entries in Owen Hatherley’s guidebook to Britain’s modernist buildings. The lavatories are ‘an exemplary “small architectural form”, as they called them in the USSR’. The entry is indicative of the book – moving from a caustic characterisation of a provincial town to an impassioned description of the qualities of a building normally overlooked, always attuned to the wider international and historical context, all of it finished off with a dose of political polemic; in this case about the egregious state of public places to pee.

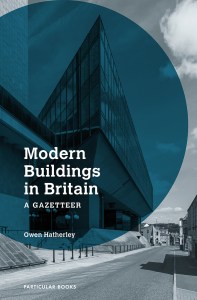

Britain is lucky with its architectural guidebooks. They are often strongly suffused by the character and idiosyncrasies of their creators – whether it is the encyclopaedic whipcrack of Nikolaus Pevsner, the lyrical gusto of Ian Nairn, or John Betjeman’s combination of surrealism and sentimentality. Modern Buildings in Britain firmly places Hatherley in this (male-dominated) pantheon. It is a guidebook that doesn’t need to be taken on the road, but is evocative enough to be read happily by the armchair tourist. Hatherley’s personality is conspicuous throughout. His descriptions of the thrill of his favourite places are contagious, whether it is of a motorway retaining-wall in Kidderminster or a milk bar in Eastbourne.

It would be possible to criticise the coverage – what counts as modernist or modern is slightly shakily set out – and Hatherley has some blind spots. Some seriously good churches, for instance, are missed. William Whitfield is a more substantial architect than allowed for here. The omission of inaccessible private houses is probably justified, but skews the history. I wish he had included Northern Ireland; and a section on important demolished buildings would have been welcome. Sniping is petty, though: this book is a tribute to some major burning of shoe rubber (the author doesn’t drive). I had half hoped Hatherley might have missed some of the more geographically obscure masterpieces of the period. Surely he hadn’t visited the astonishing brutalist Coleg Harlech, forceful concrete buildings nestled like the nearby medieval castle into the North Welsh coastal cliffs? But, yes, he has been, and rightly identifies its derelict state as a serious scandal. It is one of far too many buildings in the book where one worries the entry may serve as an obituary.

It would be possible to criticise the coverage – what counts as modernist or modern is slightly shakily set out – and Hatherley has some blind spots. Some seriously good churches, for instance, are missed. William Whitfield is a more substantial architect than allowed for here. The omission of inaccessible private houses is probably justified, but skews the history. I wish he had included Northern Ireland; and a section on important demolished buildings would have been welcome. Sniping is petty, though: this book is a tribute to some major burning of shoe rubber (the author doesn’t drive). I had half hoped Hatherley might have missed some of the more geographically obscure masterpieces of the period. Surely he hadn’t visited the astonishing brutalist Coleg Harlech, forceful concrete buildings nestled like the nearby medieval castle into the North Welsh coastal cliffs? But, yes, he has been, and rightly identifies its derelict state as a serious scandal. It is one of far too many buildings in the book where one worries the entry may serve as an obituary.

Owen Hatherley is something of a phenomenon, and it is difficult to discuss this book without foregrounding its author. I have met him in person only a couple of times, but it is possible to piece together something of his biography from a ballooning corpus of writings. His training as a writer was through blogging as much as it was through academia, which might explain the quality of fierce but unpedantic intellectualism. It also perhaps accounts for his graphomaniac tendencies; there have been single years in which he has published more than one book. He was born in Southampton, the child of Trotskyists, and his home city inculcated him with an interest in everyday post-war modernism and his first book, Militant Modernism (2009), is dedicated (surely uniquely) to Southampton’s municipal architects’ department.

In a series of explorations of British cities, originally published in Building Design magazine, he developed an argument about Britain after 1945. After decades in which the consensus about modernist architects and planners was that they were misguided to the point of malevolence, Hatherley celebrated the buildings of this loathed period for their optimism, egalitarian ambition and sheer visceral punch. It was an immensely influential argument, not least because it was a useful stick with which to beat the architecture and political consensus of the neoliberal present, which was characterised by contrast with a prelapsarian post-war era as gimcrack and morally bankrupt. Whether or not one agreed with the politics and history, Hatherley reinjected into an architectural discourse dominated by vacuous style wars a sense that the built environment mattered on a deeply ethical level. Fiery, crusading and prolific, Hatherley is a ‘béton brut’ Ruskin for the 21st century.

Modern Buildings in Britain is the culmination of this project. I share most of the author’s aesthetic, and many of his political, proclivities. For an existing believer like me the book is a triumph and a thrill ride. A great big doorstopper, it is a classy production generally, generously illustrated with Chris Matthews’ superb photography in both colour and black and white.

Will it convert the majority of the population who still think that modernist architects, with their ‘concrete monstrosities’, inflicted damage on the urban environment that was somehow ‘worse than the Luftwaffe’? Possibly not, but several useful arguments do emerge from the text. The historical overview in the introduction is a masterpiece of lucid, pithy explication, which roots British modernism in a longue durée stretching back into the 19th century, countering the suspicion that it was a purely foreign importation. This is also a history which blows apart any idea that modernism becomes diluted and less interesting the further it gets from some unsullied interwar source – he celebrates the concrete council housing of the 1960s much more effusively than the rarefied white cubes of the 1930s. Hatherley’s frame of judgement is alternately aesthetic and political, but some of the most interesting writing occurs when these don’t align, as in Richard Rogers’ Lloyd’s Building in the City of London, which he adores despite what it represents. The introduction groups modernism into at least 15 variants, and I think any but the most hostile reader will be struck by the wonderful range of Britain’s modernist buildings. Hatherley isn’t, in fact, a modernist ideologue, in that he doesn’t hold some pure ideal against which buildings are judged. Modernism emerges in this book as happily eclectic. It is often extraordinary, but it is also everywhere and everyday and, although much of it remains unloved, it has found in Hatherley a brilliant advocate.

Modern Buildings in Britain by Owen Hatherley is published by Particular Books.

From the June 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?