To think of American Pop Art, for most, is to think of Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein. Their catchy and, for some, bland idioms have made them an irresistible crutch for documentary makers and art teachers. But in the shadow of these looming figures can be found a rich undergrowth of art which deserves attention.

To that end ‘Tom Wesselmann: Collages’, now on show at David Zwirner, is a good place to start. Wesselmann (1931–2004), together with James Rosenquist and Jim Dine, represents a side of Pop Art more sensual – and more thoughtful – than Campbell’s soup cans and Marilyns. This much is already evident in Wesselmann’s collages, intimate works made in the late 1950s and early 60s.

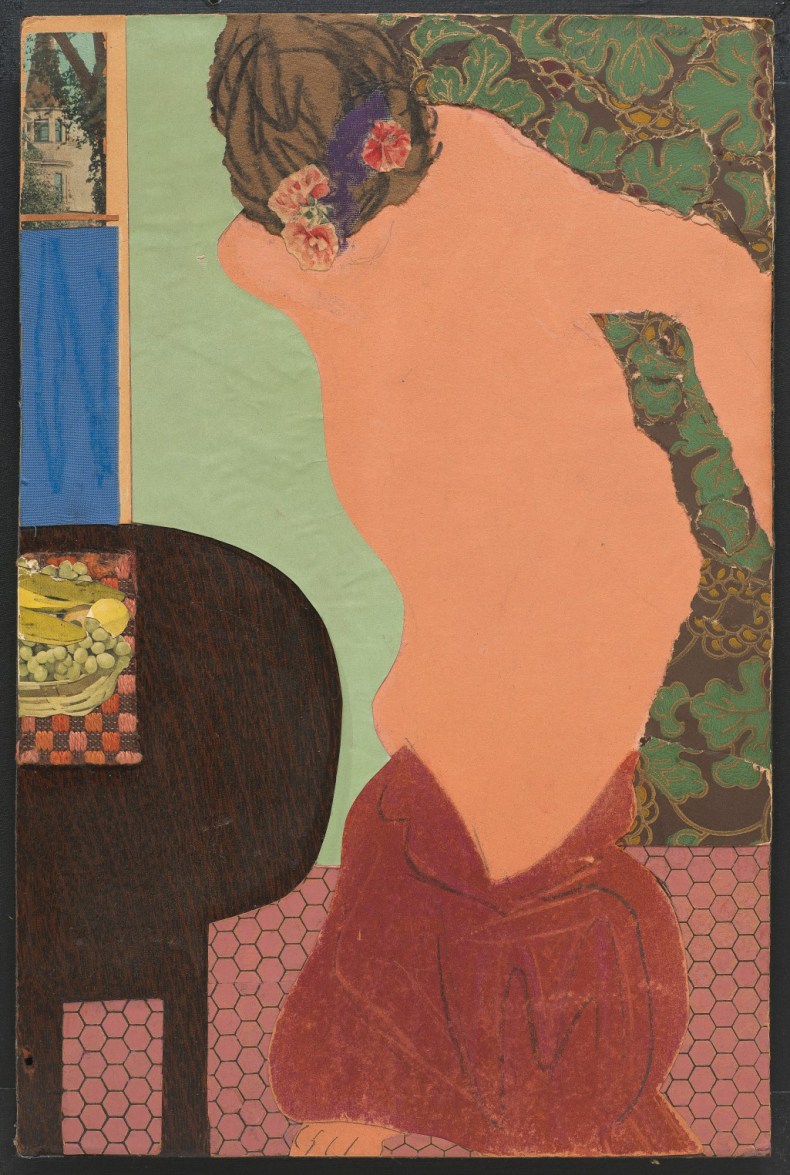

Judy Undressing 1960, Tom Wesselmann © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, Photo: Jeffrey Sturges

These have been neatly divided into three rooms at David Zwirner in London. First is a series he titled ‘Portrait Collages’ miniature interior scenes each occupied by a figure crudely drawn in pastel and surrounded by various scraps and cuttings: a square of wallpaper, a leaf signifying a tree behind the window. These works have the naivety and exuberance of a child’s scrapbook and if, like me, you have a soft spot for that sort of thing, these collages alone are worth the trip.

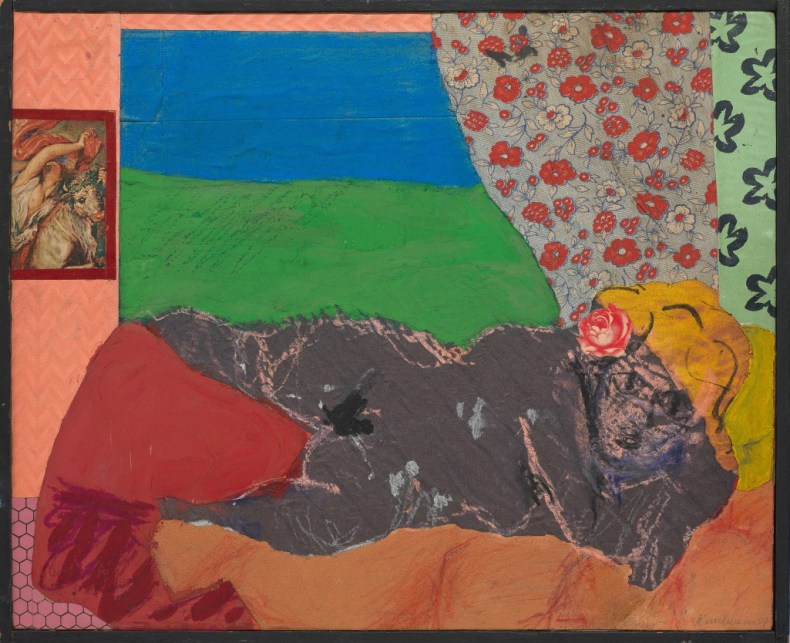

Blue Nude 1959, Tom Wesselmann © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, Photo Credit: Jeffrey Sturges

Next are the equally tiny collages known generically as nudes, although these were constructed around sketches of real models, some of who are mentioned in the titles. They are closely modelled on classical Renaissance compositions or, in some instances, such as the odalisque Blue Nude (1959), on Wesselmann’s lifelong inspiration Matisse.

The upper part of the gallery is devoted to a few bold, large-scale works that grew from the smaller studies. Little Great American Nude #1 (1961) was the first of the long series that would make Wesselmann’s name. By this time, in the early 1960s, Wesselmann was contacting advertisers directly to get his hands on billboard posters. He combined parts of these, such as the shiny two-foot-high apple of Still Life #29, with painted elements and bright backgrounds in humorous but disarmingly complex arrangements.

Installation view of Still Life #29 1963, Tom Wesselmann © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

With these collages Wesselmann was feeling his way past the Abstract Expressionism that had dominated the 1950s. Like the other nascent Pop artists (of whom he was still unaware), he sought inspiration from the rampant, giddy consumer-culture blooming around him. But what made Wesselmann more interesting many of his contemporaries was the way in which he reached back through art history, treating the imagery of pop culture as a continuation of, rather than a break with, the past.

Still Life #44 1964, Tom Wesselmann © Estate of Tom Wesselmann/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, Photo: Jeffrey Sturges

Wesselmann’s work, especially concerning the female form, was uniquely warm and voluptuous compared to most Pop Art, as it sought out the element of desire that flowed from the Renaissance nude right through to the advertising billboard. His detached view of pop imagery meant he was able to analyse it coolly and expose it as just another system of signs.

Wesselmann was uneasy with the Pop label from the beginning, and these sensitive collages make the association seem more like a burden. At this stage it would be better to compare to the enigmatic and curious Jasper Johns, a bemused observer of American life.

Tom Wesselmann: Collages 1959-1964 is at David Zwirner, London, until 24 March.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?