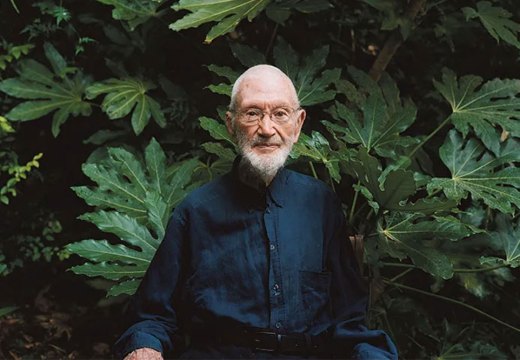

For Keith Coventry’s first venture into making collages – which are currently on display at Upstone Soho – the artist has combined Bauhaus aesthetics with ancient Athenian comedy. He talks to Thomas Marks about the intuitive nature of making collages – and why there’s nothing funny about a block of frozen kebab meat.

What spurred you to take up collage for these works?

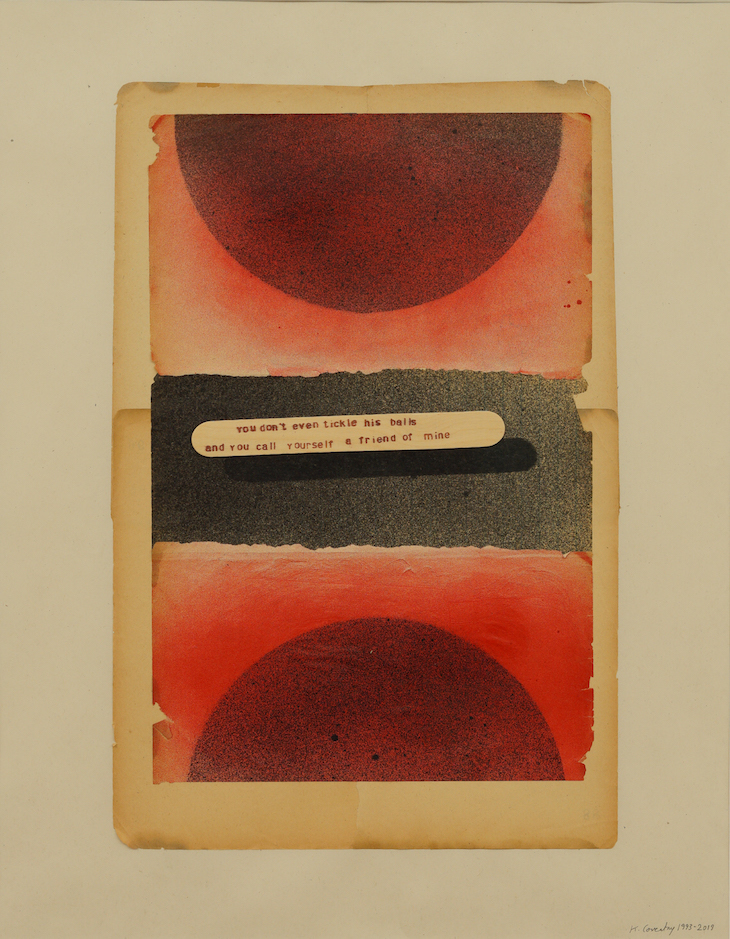

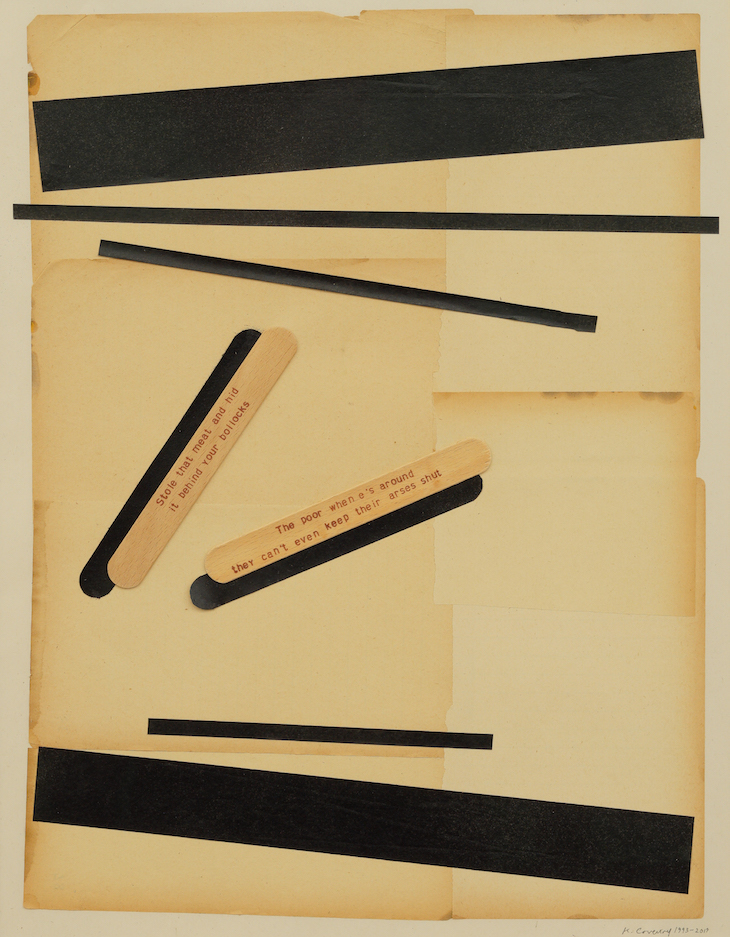

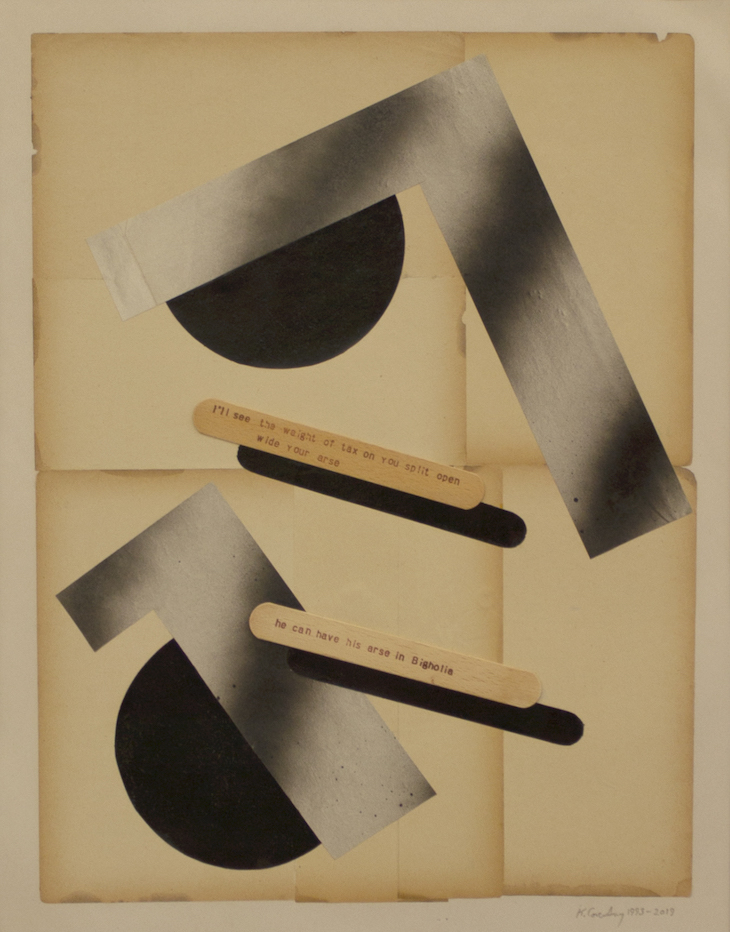

I made the lollipop sticks as an edition for Ridinghouse Editions back in 1993, in a nice linen box. [The art dealer] Robert Upstone saw them recently and said I should get them out of the box. I thought about what kind of support I could put them on, and realised I had all this very old paper, 80, 90, possibly 100 years old, which felt like the ideal thing – fitting in with the Bauhaus centenary but with the lollipop sticks, which are like a Pop image, but which have lines from Aristophanes printed on them, from the fifth century BC. The two shouldn’t really go together. There’s an absurd aspect to these works, too, in putting the various elements together.

These are the first collages I’ve done. I really enjoy it, because even if you make a mess of one, you just cut out what you think is the successful part and bring it back in later. It’s a very fluid and incredibly intuitive way of working.

So how do you know when a collage is finished?

Well, I could just leave them unglued and spend days or weeks just pushing them around like little elements on a board, but there’s something about committing to gluing them down permanently that forces you to say, ‘Right, this is it.’ And if it doesn’t work out then you have to cut it out and start again.

With my other work everything is a given – with the Estate Paintings the plans are already worked out. With these collages, for the first time in a while, I’ve had to rely on intuition. When I start one I’ve no idea how it’s going to turn out. I think some people are better at intuition than others; it brings out the feminine side in you, so they say.

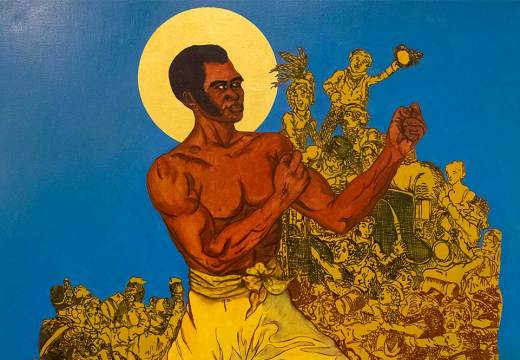

No. 6 (1993/2019), Keith Coventry. Courtesy Upstone Soho

How do the jokes from Aristophanes work with or against the Bauhaus aesthetic of the images? The Bauhaus movement isn’t known for its sense of humour…

… Except I just watched this BBC documentary about the Bauhaus and it seemed like there was a party every week, huge parties with people who had very, very different political views. Images flashed up of young people at a school who looked very similar to punks. Maybe there’s something a little punky about putting lollipop sticks into a Bauhaus-style composition – I think they would have approved. Not everything they did was about form and function. A lot was just playful experimentation.

There’s something in your title, ‘The Old Comedy’, which – however much it refers to the ancient theatrical tradition of which Aristophanes was a part – also feels like a way of saying that old jokes don’t always stay funny.

Like the whole idea of footnotes, trying to explain art is something that I’m not really interested in. If the first thing you do is read the footnote before looking at the piece, you’ve already got someone else’s understanding of what it’s about, rather than your own subjective response to it. I think looking at these works is like picking up a copy of Private Eye, this week’s copy, which would be funny – but a copy that you look at from, say, 25 years ago, would probably have some names that have been forgotten. Some of the jokes wouldn’t have the same kind of ring to them.

No. 13 (1993/2019), Keith Coventry. Courtesy Upstone Soho

‘May he drop his shield like Cleonymus…’, for instance. I suppose that tallies with the idea that these jokes are printed on lollipop sticks, like they used to be – a joke reproduced on something that’s ephemeral, which you then toss away?

I always liked the idea that when you buy something, you get a bonus – you buy the ice lolly and when you’ve consumed that you get a joke. It’s a bit like buying boxes of cereal when you’re a child and there’s something at the bottom of the packet.

With the lollipop sticks, I like the fact that it’s a bit like Kurt Schwitters going around picking up old bus tickets – not that I actually picked them up, because they’re not actually lollipop sticks, they’re tongue depressors. I got them from Pearl Paint, which was the famous art shop on Canal Street in New York. It was like a wonderland of all sorts of materials. I brought them back from New York knowing exactly what I was going to do with them, printing the lines from Aristophanes on them.

Do you think a lot about comedy?

Not really, but I was recently in an exhibition about comedy at a museum in Belfast. They exhibited my Estate Paintings, and I was a bit bemused as to why they thought they were comic. I made them to be very serious things, but in other people’s eyes there was some comic irony to them. When I made the lollipop sticks, I did read plays like Lysistrata, The Frogs, The Birds. Then I made my history paintings too, and read through Herodotus and various other things. It was quite an unlikely thing for a so-called YBA to be doing, that sort of research. The plays didn’t seem that funny when I read them to myself but at the time. But The Birds was on Radio 4 and Lysistrata was on in London somewhere – you need the whole chorus thing going.

I think in a lot of my work there could be an element of humour somewhere – but it’s not particularly funny. You know, that sort of unfunny humour. Even with the kebabs, the bronze spinning kebabs. I actually went and bought one of those entire frozen blocks of meat from a wholesale kebab place, cast it, trimmed it down and cast it again and then trimmed it down to the skewer. And then I was left to work out how to dispose of all this kebab meat in the middle of a hot summer.

No.2 (1993/2019), Keith Coventry. Courtesy Upstone Soho

As soon as you put a joke in a frame, and behind glass, it’s held up for scrutiny. Do you want these jokes to challenge the people who look at them?

There’s one particular joke that says ‘I’ll see the weight of tax on you split open wide your arse’. Someone who’s very rich might enjoy that, as a reminder of the fact that they’re sort of escaping paying tax in some way. […] It concerns me that people would find Aristophanes’ jokes offensive. If they do, it means that we’re into a new era of Victorian morals when it comes to art and writing. These are quite mild, I think, in comparison to Catullus or Martial.

‘The Old Comedy: Collages by Keith Coventry’ is at Upstone Soho until 13 December.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?