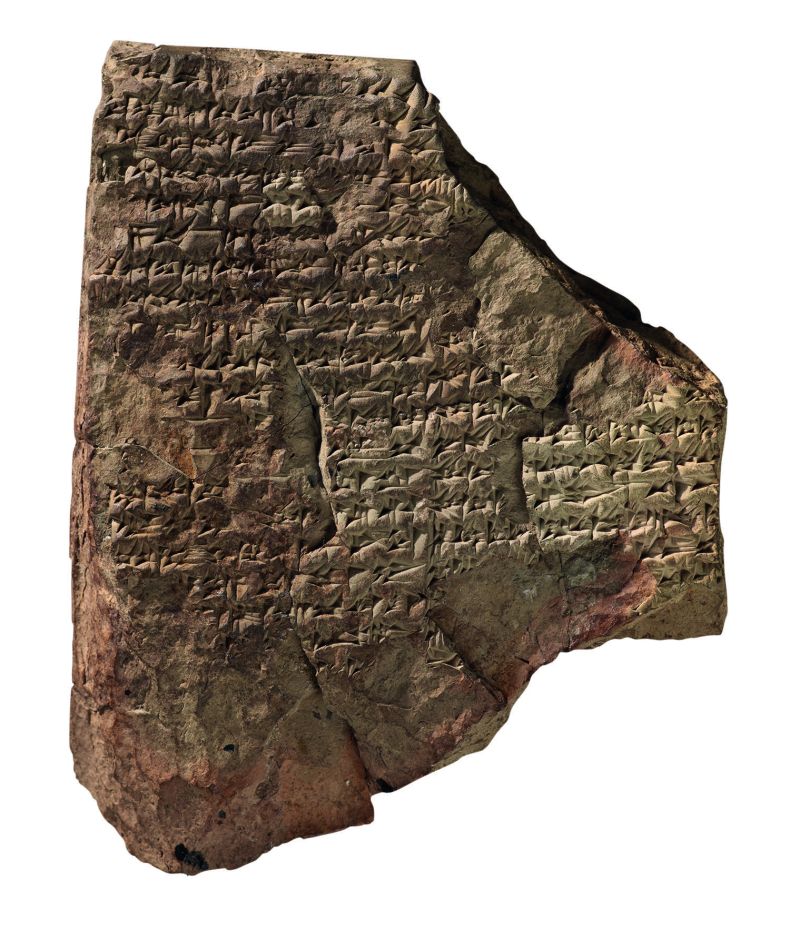

According to Mesopotamian myth, humans were created by the gods as their servants but – as revealed in the so-called Epic of Atrahasis, inscribed on clay tablets from the period 1900–1600 BC – they soon multiplied and their noise began to disturb the sleep of the supreme god Enlil. He sent diseases and a drought to reduce their number, but eventually decided to destroy humanity by sending a flood. Recognising the folly of such an act, the wise god Enki told his servant Atrahasis to dismantle his house and build a boat. Atrahasis put aboard his family along with birds and, in a frustratingly broken part of the tablet, possibly domesticated and wild animals. The flood ‘roared like a bull’, but Atrahasis survived to make the gods an offering, after which Enlil introduced various forms of infertility to keep overpopulation in check.

The story was clearly a way of explaining some of the major challenges of life on the floodplains of Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). Of course, it also has parallels with the account of Noah’s flood in the Hebrew Bible that has inspired countless artists from late antiquity onwards to portray animals entering the ark two-by-two. Animals hardly figure in the Mesopotamian text, but it is clear from the extraordinary art that survives from the region that they played a significant role in the often tricky relationships between the inhabitants and their gods.

Cuneiform tablet inscribed with a fragment of the Epic of Atrahasis (c. 1646–1626 BC). Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Although representations of animals in paint and small-scale sculpture occur as early 40,000 BC, it is during the Neolithic period, from around 10,000 BC, at places like Gobekli Tepe in south-eastern Turkey, that carved animals in very high relief are associated with monumental architecture intended to create sacred spaces. This was the era in which the transition from hunting to herding and permanent agricultural villages took place. The rich symbolism of wild creatures, which had probably long been linked with the supernatural world, now incorporated domesticated animals; these are represented in fragile wall paintings and moulded reliefs at villages such as Çatalhöyük.

By around 4500 BC stone stamp seals engraved with abstract designs of animals were being impressed on lumps of wet clay or plaster; these were placed on the fastening of baskets, ceramics, sacks, and storeroom doors to define individual property and to secure, perhaps magically through the power of the animals depicted, the containers and rooms against unauthorised opening. More intriguingly, it is in these same villages within the foothills and passes of the Zagros Mountains, which divide the lowlands of Mesopotamia from the high plateau of Iran, that stamp seals were engraved with some of the earliest known representations of a supernatural figure: a being that combines a human body and the head of an animal with long, curved ibex horns. The relationship between humans and animals at a supernatural level had become entwined in art; originating in the mountains of Iran, this tradition would have a profound influence on Mesopotamian beliefs and representation for thousands of years.

Head of a ewe (c. 3300–2900 BC), Sumerian. Kimbell Art Museum

It is, however, the centuries around 3300 BC that are the starting point for an exhibition exploring Mesopotamian sculpted animals at the Morgan Library and Museum (26 May–27 August). The world’s earliest states and cities emerged in this period and with them some of the most accomplished representations of animals that have survived from the ancient world. In the far south of Mesopotamia, at the head of the Persian Gulf, lay the city of Uruk, which by this date was home to tens of thousands of people, sustained by fields of grain and vast herds of cattle and flocks of sheep. Here mud-brick temple buildings were constructed on a monumental scale (one had a floor plan comparable in size to that of the Parthenon built in Athens some three millennia later). Associated with this architecture were sculptures of animals in both clay and stone, representing cattle and sheep, and the lions that threatened them. The skill to imitate the natural form of living animals is very evident in many of the carvings, not least in a remarkable head of a ewe. Carved from sandstone, the sculptor’s mastery of the medium allowed them to capture the vitality of the animal with her floppy ears standing free of the head. Although this piece is without provenance, it is very similar to excavated examples found in the so-called Sammelfund hoard at Uruk, which may have been a range of stores for temple equipment. The rooms contained objects in the form of animals and many of the stone figurines, which are often inlaid with precious stones and metals from the highlands of Iran or further afield, were probably intended as votive offerings.

This same era saw the development of the cylinder seal. Although these are perhaps the most characteristic objects from Mesopotamia, the earliest attested example comes in fact from Susa in south-west Iran. The engraved stone cylinders were impressed into clay by rolling, but their shape provided a greater surface area than earlier stamp seals, which allowed the carver to play with patterns as well as complex narratives. The first cylinder seals show rows of animals such as fish and cattle, as well as human workers, and they may have been used by administrators responsible for different ‘departments’ of large agricultural estates, some of which almost certainly belonged to temples. Indeed, a number of seals appear to show temple flocks and herds, including a fine example carved from serpentine, with a ewe and ram flanking a plant. Between the rumps of the animals is a pole with a loop and a streamer at the top. This is the symbol of Inanna, the patron goddess of Uruk and a powerful deity associated with abundance and sexuality. Although the animals face each other on the seal, the composition might be intended as an open-ended, infinitely repeating design. When the seal is rolled, the symbol of Inanna is repeated so that it appears to frame the two sheep and, given sufficient clay, the animals could be multiplied as would be befitting a goddess of procreation and plenty.

Other seals from the late fourth millennium BC evoke a supernatural realm through representations of fantastic creatures such as bird-headed lions and heraldically composed snake-necked felines. The latter are known from seal impressions not only at Uruk and Susa, but also at sites in Syria and on elite objects associated with kingship in Egypt where their exotic, prestigious values lent them an otherworldly status and power. These images had presumably been transmitted to the Nile Valley through portable cylinder seals or their impressions on imports. Like the earlier horned figure on stamp seals, these beings violate basic expectations of the natural world and as a result they may have been more easily memorised and transmitted without the need for language. In societies focussed on trade routes, such as those along the foothills of the Zagros range and within the mountain passes, composite figures may have played a crucial role in negotiating the risk and uncertainty posed by cultural, social, and political differences.

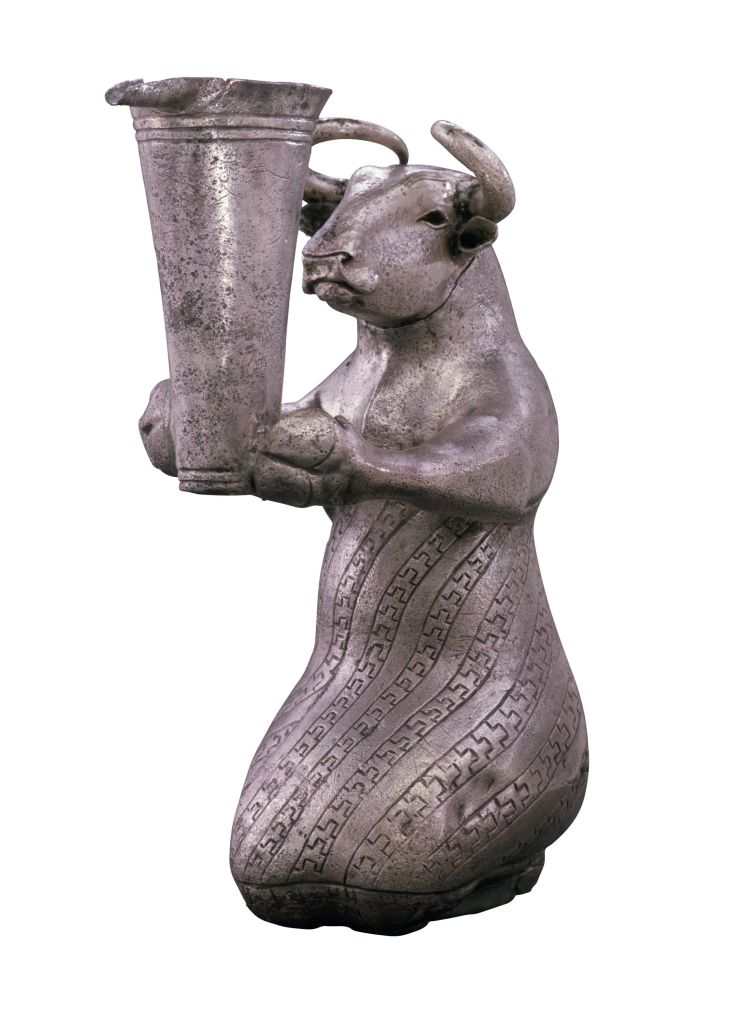

Kneeling bull holding a vessel (c. 3000–2900 BC), Proto-Elamite. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Although movements of people reoriented long-distance trade routes around 3000 BC, Uruk and other cities of southern Mesopotamia (Sumer) continued to flourish and there was much continuity in their art. To the east, in Susa and across Iran, however, new ideas built on ancient highland traditions came to the fore. An emphasis on animals with elaborate horns emerged; some cylinder seals show them standing in parallel rows where the lower animals are depicted larger than those above, an arrangement that may indicate perspective. Other horned animals are shown flanking a tree emerging from a mountain. These images are typical of seals from the so-called Proto-Elamite period of Iran (around 3100–2900 BC) when decorum appears to have required the avoidance of representations of humans, a significant feature that distinguishes them from the seal designs of Sumer. Instead it is animals who assume poses more appropriate to humans, a concept that is also found in a number of extraordinary stone and metal sculptures. One of the most outstanding is a silver kneeling bull. It is formed from many pieces of metal, which have been fused together to represent an animal wearing a garment patterned with an interlocking striped design and offering a spouted vessel. The haunches and legs of a bull replace the shoulders, arms and even the legs of a human. The kneeling pose is known from other Proto-Elamite sculptures as well as cylinder seals where lions, bulls, bears, and ibex are shown paddling coracles, playing games, banqueting, or acting as scribes (writing on clay tablets had been developed in both Mesopotamia – the forerunner of cuneiform – and Proto-Elamite Iran). The bull contains a number of small pebbles, which may suggest that he served as a rattle, perhaps for ritual use.

The combination of distinct architecture, ceramics, and writing that characterises the Proto-Elamite period disappears at the start of the third millennium BC, but some of the traditions in representation appear to be maintained in the western Zagros. It becomes apparent in images on seals found at sites in the Diyala river valley, east of modern Baghdad and at one end of an important east-west route across the mountains. Here appears a bison-man, a creature standing upright on bison’s legs with a human torso, arms and face, with bison’s ears, mane and horns. Early depictions of human-faced bison on seals and their impressions from Sumer also show them in a recumbent pose on either side of a mountain from which sprouts branching vegetation that evokes an earlier Proto-Elamite tradition. These composite creatures are often associated with a lion-headed bird (called Anzu or Imdugud in cuneiform documents) which can be shown with closed wings, its body in profile but head lowered and viewed as if from above, and perched on the back of the human-faced bison that it bites. The scene has been interpreted as representing the thunder clouds (symbolised by Anzu) that occasionally obscured the eastern Zagros Mountains (the human-faced bison) when viewed from the lowlands. An interest in pictorial depth, suggested by the use of perspective in Proto-Elamite seal imagery, is implied by the use of registers, separating the natural, animal world of Sumer in the bottom from distant, mythological realms at the top.

‘Ram caught in a thicket’, from the Royal Cemetery of Ur (c. 2500–2400 BC), Sumerian. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Courtesy of the Penn Museum and Dorling Kindersley

This relationship between natural and supernatural animal worlds is demonstrated by the remarkable objects uncovered in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, the centre of a powerful Sumerian city-state at the head of the Persian Gulf around 2500–2400 BC. Among the masterpieces is a pair of sculptures in the form of a male goat rearing on its hind legs up against a flowering plant. Each of the sponsors of the excavations at Ur – the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum – received a goat. The figures were not, however, designed as separate freestanding sculptures but rather as pieces of applied art; the gold covered cylinder projecting from the goat’s neck possibly supported with its partner a small tray. The goat’s horns, beard, eyebrows, pupils, forelocks, and the fleece of the shoulders and chest are made from blue lapis lazuli, a stone imported from Afghanistan, far to the east.

The underside of the body is made of silver, possibly originating from sources in the region of modern Turkey or Iran while the remainder of the body fleece is formed of shell, perhaps from the Persian Gulf. Iran may have supplied the gold that covers the goat’s face and legs, as well as the plant. The animal embodies the trading connections that crossed the ancient world and the exotic materials demanded and acquired by the wealthy elite of the Sumerian city states. Yet the imagery also embraces the divine world since the stylised plant has produced five buds and three flowers or rosettes that are understood as symbols of the goddess Inanna. The active male goat and the passive plant encapsulates the fertility and abundance provided by the gods.

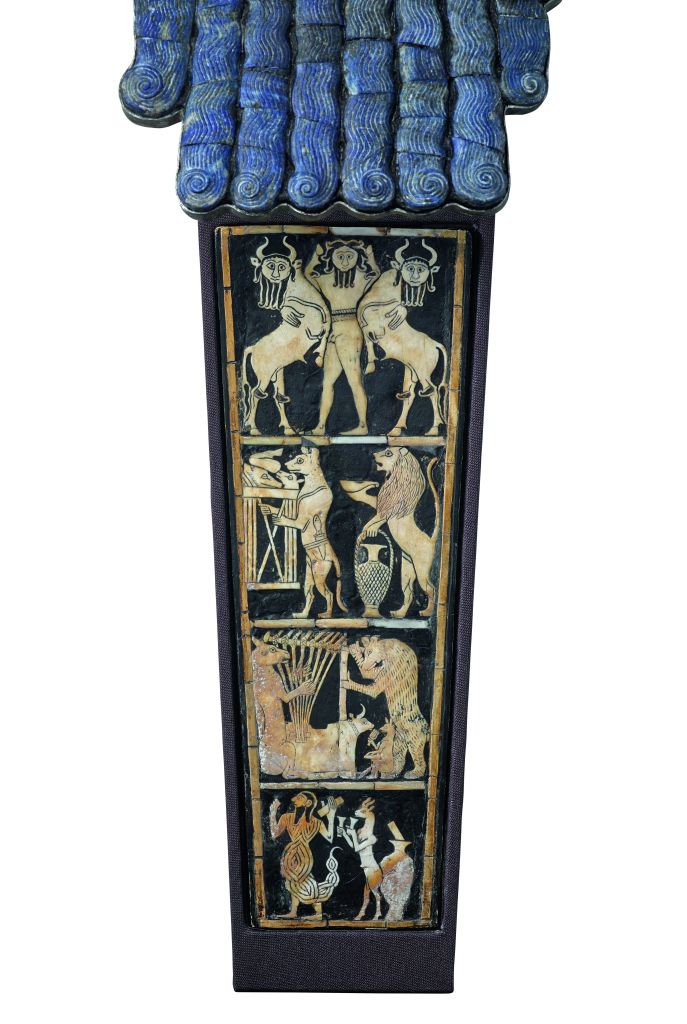

Inlay of the ‘Great Lyre’ from the Royal Cemetery of Ur (c. 2500–2400 BC), Sumerian. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. Courtesy of the Penn Museum and Dorling Kindersley

Many of the objects from the Royal Cemetery are fashioned from materials from the mountains of Iran and further east. For the Sumerians this direction could be described by the word kur (earth/mountains) that designated both a foreign land and the netherworld. Entrances to the netherworld were thought to be within the mountains and it may be that the objects in the tombs were intended to accompany the dead on that eastern journey or be presented as gifts when they arrived. In this way, the spirits of the dead would be returning the stones and metals to the place where they originated in reality, but now in a supernatural realm. But how was the netherworld imagined in Sumer? One vision appears on a shell plaque decorating the front of a large lyre from the cemetery. In the top register a nude belted hero holds two human-faced bison. If the bison stand for the eastern mountains, then the hero may be the gatekeeper who, as a later Sumerian myth describes, confronts Inanna when she attempts to visit the underworld. In the panels below the hero the scenes depict a banquet, but this is an ‘other world’ in which animals replace humans as servants and musicians. In the lowest register appears a scorpion-man, a creature associated with distant, mysterious lands. Thus the eastern mountains and the Iranian conceit of animals acting as humans are brought together to represent a distant cosmic realm.

Looking at Mesopotamian sculptural works from about 3300–2250 BC reveals an intimate link between Sumerian gods and the animals that symbolised and embodied their powers. Dedications of animals in temples, either as living sacrifices or finely crafted images, were believed to ensure divine support in maintaining the fertility of the land and protection from the dangers of the wilderness beyond. But this was only one aspect of the complex relationship between humans, gods and animals. To the east of Sumer, the societies of Iran supplied metals, exotic stones, and strong timber not available in the lowlands and this gave them economic and political, and also cultural influence. Imagery of horned animals, composite creatures, and animals acting as humans, which were at home in the mountains, was fundamental in shaping Sumerian approaches to the divine and the creation of associated art. We therefore cannot understand the plains of ancient Mesopotamia without considering the influence of the highlands, a notion that continues to be relevant in the modern relationships between Iraq and Iran.

‘Noah’s Beasts: Sculpted Animals from Ancient Mesopotamia’ is at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, from 26 May–27 August.

From the June 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.