The Newbattle Abbey casket is a 16th-century treasure in itself, and if no UK-based institution, organisation or individual registers an interest to save it for the nation by 11 July, the government will have no choice but to grant its owners an export license and it will leave these shores. Why it should not is straightforward. Quite apart from the fact that there is nothing else quite like it in the country – and that it is the only dated example of some 11 pieces around the world thought to come from the same workshop – it is one of those rare works of art of exceptional ingenuity and aesthetic appeal that also bears witness to a very specific time and place.

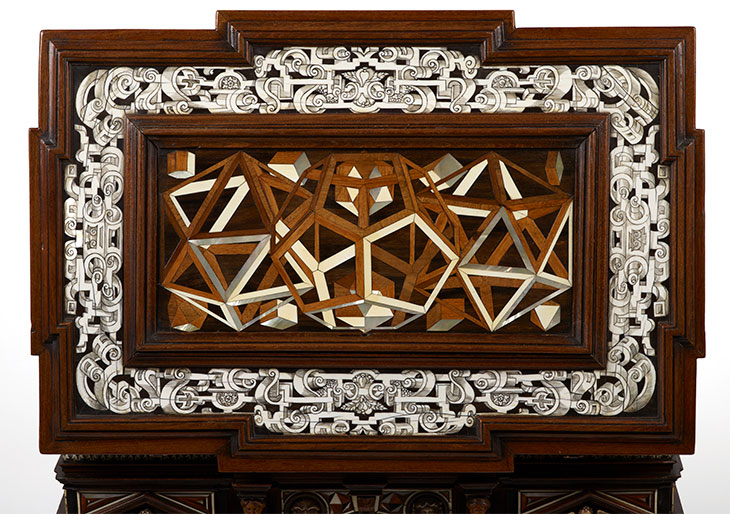

That time is approximately 1565 and the place is Nuremberg, and this casket may be seen as a proud reflection of the intellectual, scientific and cultural accomplishments of the free imperial city. It is modelled on the architectural form of an Italianate palazzo, rising from a rusticated base and complete with pilasters, pedimented windows, architraves, friezes and cornicing, and ornamented with three-dimensional herms, lion masks and cherubim. Its materials are precious, and include ebony, alabaster, and mother-of-pearl. Most striking of all, however, are the images and scenes within the ‘windows’ – bone plaques engraved with female personifications of the four temperaments and four cardinal virtues, and historical and biblical scenes – and the illusionistic representations of complex polyhedra that decorate the casket inside and out.

Side view of the Newbattle Abbey Casket. Photo: Matthew Hollow

It was the 14th-century Sienese who first took the ancient technique of intarsia – inlaying sections of usually contrasting woods – and transformed its abstract patterns into the representational. It was also in Italy – in Florence, a century later – that Brunelleschi’s experiments with linear perspective were developed, and that wood decorations featuring perspectival renderings of polyhedra appeared. The translation of the visual perception of the three-dimensional into a system of lines to create a simulated reality is key to the enduring fascination of this intarsia work – as well as the reason that until recently it was thought to have come from an Italian workshop.

It was in mid 16th-century Nuremberg, however, that the polyhedron became a pictorial motif in its own right. This was a city of celebrated humanists, artists and mathematicians, and the geometric solid – whose various forms had long been considered the building blocks of the universe – stood as a symbol of their combined achievements. The design of ever more complex polyhedra was aided by new mechanical perspective devices made for the use of artists – not least that devised by the goldsmith and artist Wenzel Jamnitzer, who also published a lavishly illustrated tome on polyhedra in 1568.

The lid of the Newbattle Abbey casket. Photo: Matthew Hollow

This intensely artistic and scientific milieu also produced the Kunstkammer and the Wunderkammer, in which specimens of artificilia and naturalia were bought together to represent the world in microcosm. The Newbattle Abbey casket is a particularly early example of the furniture pieces that were designed to fill these rooms. Intended to be viewed in the round, it would have been placed at the centre of its original Kunstkammer. Its first owner probably belonged to a princely family and it seems likely to have then come into the possession of Karl I Ludwig, the Elector Palatine, for his daughter seems to have brought it with her when she settled in Britain with her husband Meinhardt Schomberg, a mercenary created Duke of Leinster for his part in the Battle of the Boyne of 1690. The casket then, it is thought, passed to their oldest surviving daughter as a gift on her marriage, who in turn passed it to her daughter when she was married in 1735 to the 4th Marquess of Lothian – whose principal residence was Newbattle Abbey in Midlothian, now a college. By this time a handsome carved walnut stand had been made for what was evidently a prized possession, probably by James Moore, around 1720.

The casket and stand remained in the family until 2017 when it was sold at Sotheby’s by the 13th Marquess, better known as the Conservative politician Michael Ancram. Unlike the pair of Assyrian reliefs from Newbattle Abbey which had recently been sold by Ancram and the college for £8m by private treaty sale, this previously unpublished casket sold for £118,750 – a price a little above its auction estimate but still widely regarded as a song, perhaps depressed by the casket being described as containing ivory (now identified as bone) and the sure knowledge that its export would be deferred. The buyers were Kunstkammer Ltd, the London arm of Georg Laue’s Munich-based gallery, and Trinity Fine Art.

In the hope of attracting an institutional buyer in the UK, Laue exhibited the casket at Frieze Masters last October, and it will be presented once again next week – this time with a thorough scholarly catalogue – as a highlight of London Art Week (Trinity Fine Art, 15 Old Bond Street, London, 25 June–25 July). The asking price is £750,000, although if a British institution were to express serious intent, this and the terms would be negotiable; and the export bar would be extended until 11 October to allow time to raise funds.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?