From the May 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Museums in Los Angeles were given the OK to reopen last month after a year of enforced closures. For many museum-goers, this meant a welcome return to familiar cultural institutions that had pretty much sat dormant for the past 12 months, with some exhibitions installed, but never seen by the public. However, the situation at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is markedly different. Shortly after the start of the pandemic, LACMA began the demolition of much of its campus. The museum has been in the midst of a controversial and costly overhaul, which involves the destruction of four buildings, to be replaced by a unified, undulating structure designed by the Pritzker prize-winning Swiss architect Peter Zumthor. What remains meanwhile are two fairly recently built structures designed by Renzo Piano – the Broad Contemporary Art Museum and the Resnick Pavilion – and Bruce Goff’s Pavilion for Japanese Art. Visitors who returned to LA’s encyclopaedic museum when it reopened on 1 April stepped into quite a different set of spaces than existed a year ago.

But the building changes are only one aspect of the institution’s planned transformation. LACMA’s director Michael Govan has put forth a somewhat radical curatorial scheme for the exhibition of the permanent collection. Eschewing a traditional presentation that displays art according to geographic and chronological categories, Govan has proposed a series of thematic shows that bring together objects from across various departments and collections. Not everyone shares his vision – the Ahmanson Foundation, for instance, longtime donor of Old Master works, suspended gifts to LACMA when it did not receive reassurance that its donations would be displayed in the way it expected. Govan, however, sees his approach as a challenge to decades if not centuries of staid methods of museological display that have reinforced outdated cultural hierarchies. As he told me a year ago, ‘We’re obligated to not do business as usual.’

Installation view of a room in ‘Not I: Throwing Voices, 1500 BCE–2020 CE’ at Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Ⓒ Museum Associates/LACMA

We now get to see a pilot for Govan’s vision, with ‘Not I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE)’, one of several exhibitions that LACMA reopened with in April. Organised by José Luis Blondet, curator of special initiatives at the museum, the show features more than 200 objects pulled from throughout its vast holdings, arranged around the theme of ventriloquism, interpreted both literally and figuratively. There is one actual ventriloquist’s dummy in the show, Elmer Sneezewood from the 1930s, but works by artists including Chardin, Tina Modotti, John Baldessari, Eleanor Antin and many others allude to questions regarding voice, authenticity, authority, and audience. Blondet sees ventriloquism as a metaphor for what cultural institutions such as museums and libraries do – they ask objects to speak for a place, an era, or a culture. The show is divided into 10 poetically titled sections such as ‘Not I: Dolls, dummies, surrogates, Pygmalion, and plugs’, ‘Not Silence: Bubbles, whistles, and love letters’, and ‘Not Duck, Not Hare: Out of sync’.

Soap Bubbles (after 1739), Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: © Museum Associates/LACMA

Spanning 3,500 years of art history, this is an ambitious show, and one almost bound to strain under its own weight – and indeed that is by design. Blondet has said he aimed to capture the ‘flawed ambition to represent all cultures, all ages, and all artistic manifestations of humankind’, with such a grand geographic and temporal sweep. Indeed, it is a challenge to follow the strands that he weaves between objects as you move through the exhibition. Unmoored from their origins, these artworks now play a part in a new narrative that asks us to question who is telling the stories and through which mouthpieces. It is a valid question, and one that all museums should be asking, but not at the expense of the objects’ own stories.

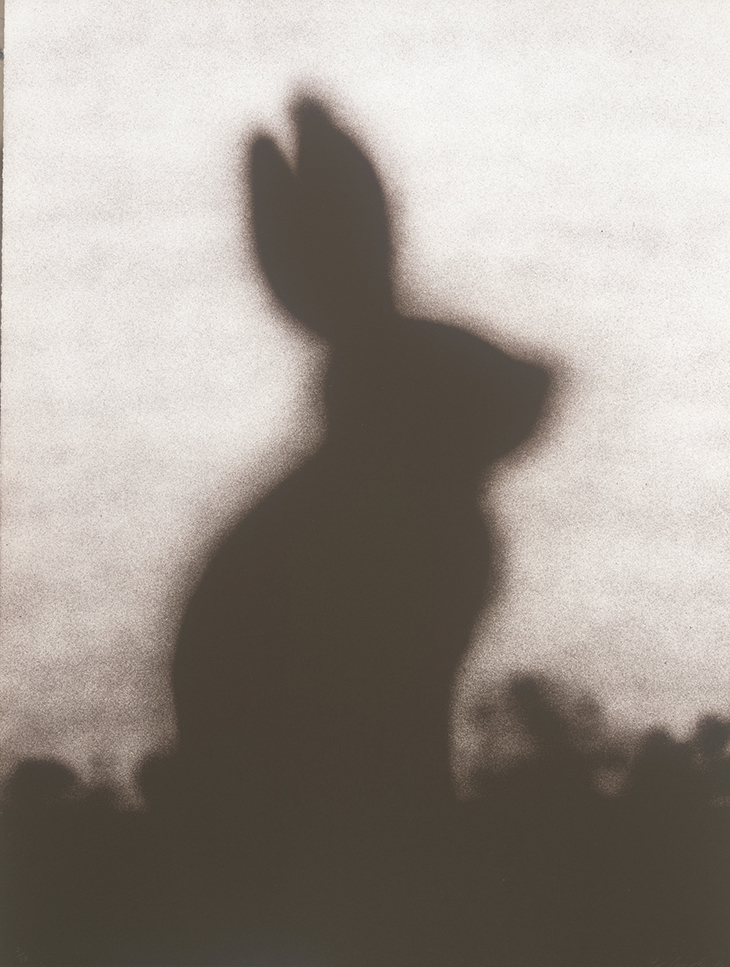

Woman Making Rabbit Shadow for Small Boy (1807), Ryuryukyo Shinsai. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA

More problematic, however, is the grouping of objects by aesthetic or functional characteristics. There are sections devoted to rabbits, ducks and pipes, which tell us little more than that cultures as disparate as sixth-century Colima in Mexico, sixth-century BC Babylonia, and mid 20th-century Los Angeles (Ed Kienholz) made art about ducks. Certain exhibits are welcome surprises, such as Joe Sola’s miniature gallery, intended to fit into the ear of his art dealer Tif Sigfrids, a video of Hannah Wilke’s striptease behind Duchamp’s Large Glass, or weirdo potter George Ohr’s vessels. There is indeed pleasure in seeing some of the artworks individually – but again, devoid of their original context, they reveal little.

A highlight of the show are the collection-inspired commissions by contemporary artists. The Spanish-born, LA-based artist Patricia Fernández has created intricately carved wooden frames for several Goya prints, representing a craft tradition that often seems overshadowed in an era of digital flotsam. Raven Chacon activated ocarinas and whistles from the museum’s collection of art of the ancient Americas, recording songs with them that are played throughout the galleries, an ethereal soundscape that spans centuries. And Puppies Puppies (Jade Kuriki Olivo) staged a performance (now on video) in the gallery in which a group of trans, non-binary, and genderqueer artists, activists, and performers stand nude in the exhibition, drawing attention to similarly noncomforming bodies that have always existed alongside these art objects, despite their lack of visibility and acceptance. A special project by Meriç Algün assembles a collection of never-borrowed books from the Los Angeles Public Library. It asks the question: ‘If a book is not read, does it say anything?’ The grouping of unopened volumes takes on a poignant significance in the age of isolation and quarantine.

Untitled (double-fold book) (2005/2020), Patricia Fernández (with José Luis Carcedo, her grandfather). courtesy of the artist, commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of

‘Not I’ is a bold statement, a timely reconsideration of what a permanent-collection show can and should be. But marshalled in the service of a new narrative, these objects and their individual histories are too easily overlooked. The permanent collection is perhaps the most democratic entry point to the museum, with something to offer both neophytes and scholars. In doing away with geographic and cultural hierarchies, ‘Not I’ aims to expand its reach even further. It ultimately fails, though not without exuberance, to strike a delicate balance between honouring these artworks’ original contexts, and creating a new way to bring them to life.

Rabbit (1986), Edward Ruscha. Los Angeles County Museum of Art Photo: Museum Associates/LACMA; Ⓒ Edward J. Ruscha IV

‘Not I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE–2020 CE)’ is at Los Angeles County Museum of Art until 25 July.

From the May 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?