‘I think colour’s very seductive,’ said Richard Serra in 2012, ‘and not always for the right reasons.’ He’s been avoiding that trap, ‘the illusion of colour’, all his career. Think of his best-known pieces, the vast curvilinear sculptures forged from weathering steel. Their hues are pointedly accidental: exposed to the air, they’re soon wrapped in rust, which might (or might not) deepen from sunset orange to a muted reddish-brown. Colour, for Serra, is never part of the design, because it’s ‘usually not structural’, and structure is what he wants.

In his drawings, he has the means of escape: black, which the philosopher Alain Badiou called the ‘non-colour’, beyond the ‘rainbow’ of everything else. Abstract Slavery (1974) was Serra’s first ‘installation drawing’: a huge trapezoid, made with blocks of black paintstick – so industrious and unseductive – on 168 square feet of Belgian linen. As art historian Neil Cox wrote in a recent essay, Abstract Slavery and its successors worked by ‘suppressing ambient light’, by ‘shifting perceptions’ of the room in which they were put. Corners and walls shifted in the viewer’s peripheral vision. Like monoliths, Serra’s installation drawings won’t bend to anyone’s wishes, won’t be pressed into the service of symbolism or representation; like their cousins, the torqued steel sculptures, they exude power and weight. In a photograph from 1974, Serra stands beside Abstract Slavery, staring the camera down. His arms are folded, jeans spattered, head shaven, jaw set.

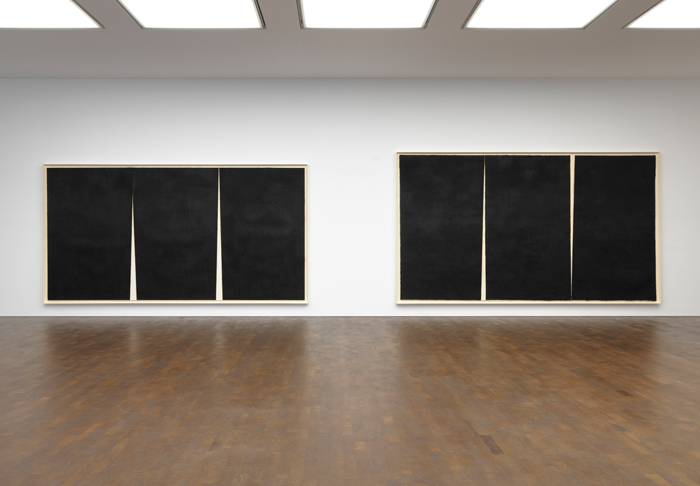

Triple Rift #3 (2018), Richard Serra. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian; © Richard Serra

Since then, his drawings have retained their brooding force, though of late they’ve occasionally leavened their pitch. The Ramble series (2015), Composites (2016), Rotterdam Horizontals and Rotterdam Verticals (2016–17) were made by transfers onto paper, producing a variegated surface – there’s scope for the viewer’s eye to play. But the Rifts (2011–), ten of which are on show at Gagosian in London, restore the monumental power of the void. Each ‘rift’ is a narrow white triangle between two large sheets of paper, which – as with Abstract Slavery – are painted black with heavy paintstick blocks. Some rifts ascend the work, some descend it; some touch the far edge with their tip, some reach only halfway. Sometimes there’s a join without a rift, and sometimes, as in the puzzling Triple Rift #1, #2 and #3 (all 2018), there are fewer visible rifts than the title suggests.

The next question would usually go something like: so what do these drawings imply? Each one is built on the neatest-conceivable varied structure – black forms, white rifts – a binary that encourages us to imagine X set against Y in some form of dynamic tension. Serra has said, benevolently, that his work is ‘about your experience of the work’, which suggests as many imagined contrasts as there are interested viewers. But his latitute apparently doesn’t extend to those who have ideas of their own as well, because – as I hear at Gagosian more than once – ‘Richard is very insistent that he doesn’t want any metaphors to be imposed’. In his essay on Serra’s drawings, Cox toes the party line: ‘the stringent intelligent structures of the Rift Drawings obstruct us from seeing their white divisions expressively as other kinds of rupture – psychological, historical, ontological.’

Quadruple Rift (2017), Richard Serra. The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian; © Richard Serra

The trouble with this, as ever, is life. Each Rift work may be, as Cox suggests, ‘capable of dominating the visual field’, but people, being dynamic unto death, are capable of moving that field around. Come within 20 feet, and you notice that the ‘ambient lighting’, far from being ‘suppressed’, exposes the incidental textures of every face and edge. You peer at the ridges and bumps of each work, distracted by multi-directional surface rather than being lost in projected depth. There are joins to spot in the works’ elaborate frames, oil marks to trace along the overlaps between sheets. Even the rifts become individual: as the lights cast shadows from above, they emphasise the upward rifts as triangles, and blend the downward ones into the walls.

Curator Michelle White, speaking in conversation with Serra in 2012 when the first Rifts appeared, said that his drawings ‘are not about something, they are something’. Interpretations like these hover around the works, sounding profound at first, then hollow, with a cultish edge. I’d suggest going to Gagosian yourself, since it’s located in the real world – a world that’s a place of proliferation, of the desire to make sense for ourselves, and in which the austere pretensions of the Rift drawings are messed up nicely by the little contingencies of life. These works are not as neat as some would claim.

‘Richard Serra: Rifts’ is at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill, London, until 25 May.