Oswald Birley looks back at us, the turn of his head catching just enough light to let us detect his expression through the shadows. His eye meets us, unmoved. We immediately get the sense that he is heading somewhere, and that this backwards glance is an impassive invitation. Painted in 1920, Birley’s Self Portrait in Profile presents a man at the start of his career. He had only recently gained recognition in 1919 when, just released from the army, he painted the daughter of art dealer Philip Agnew and was invited to hold an exhibition at Agnew’s Gallery. The show was a coup and Birley was snapped up by the bankers and beauties of America, revelling in a success the summit of which came only months before his death when he painted a portrait of Winston Churchill in 1951. Yet almost a century later he is saved from obscurity once more for a one-off exhibition at Philip Mould.

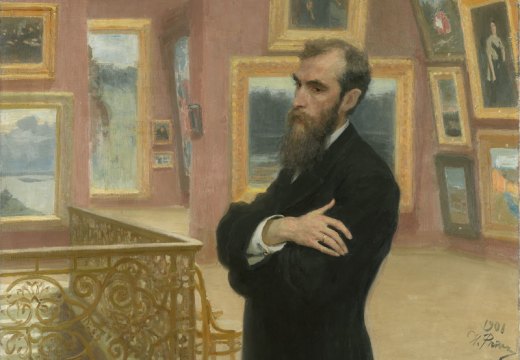

Self-portrait in profile (1920), Oswald Birley. Private collection

This remarkable gathering of portraits betrays something of the Sargentesque – softened but glitzy, real and romanticised. You wonder how the painter could have been neglected until you remember that only a year after Birley’s self-portrait, his contemporary Wyndham Lewis was disfiguring himself in Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro (1921) – a jagged image with a raised eyebrow and a snarl that must be attributed absolutely to the avant-garde. The two paintings could be centuries apart. But that isn’t all…

Almost every painting has been lent from a private collection. Families have preserved these portraits for decades, though most works would have been relatively late additions to the distinguished displays of inherited history that line staircases across the country. Left untouched for so long, each painting has been radically recontextualised in the brightly lit gallery. Prime Ministers meet performers, and royals meet rag-sorters in a sequence that is disparate, yet fitting. The exhibition prudently proposes just two broad categories for the works – power and beauty – though these have considerable overlap.

Field Marshal Viscount Alexander of Tunis (1946), Oswald Birley. Private collection

Sir Anthony Meyer, 3rd Bt (1942), Oswald Birley. Private collection

Take, for example, the placement of Field Marshal Viscount Alexander of Tunis (1946) opposite Sir Anthony Meyer 3rd Bt (1942) in a room dedicated to the powerful. One is a Field Marshal in his 50s, while the other is a 22-year-old Second Lieutenant soon to embark for service in Normandy where he will be almost killed by an exploding shell. His haunted expression seems almost prophetic; his political career is too far off to foresee. These paintings cannot be reduced to mere historical records; they communicate something distinct about each sitter and their stage in life.

The largest painting, The Theatre Box (1910), is from earlier in Birley’s career and recalls the Impressionist loge, though with none of that setting’s anonymity. Of the subjects, rakish Wilfred Egerton would have been a famous face, leering out from beneath the prominent playwright Charles Haddon Chambers. The scene borders on caricature and has a hint of social commentary – there is often a tension between the individual and the universal for Birley. The broader significance of his work, so often sequestered in stately homes, and what it says about society has been lost to the public imagination. A Birley portrait that is not in the exhibition is that of David 6th Marquess of Exeter in his Cambridge blues, in a pose reminiscent of Armine Dew (1923). It remains part of the permanent collection at Burghley House in Lincolnshire where it is an important part of the house’s history. There’s no doubt that the painting is in the right place, but perhaps it has been deprived of the chance of being seen and considered within a more expansive expression of its era.

This rare reunion of Birley’s portraits momentarily takes the private into the public realm. The catalogue speaks of ‘reposition[ing Birley] within a respected and illustrious tradition of portraiture in Britain’ and it certainly does much to illuminate his legacy.

The Theatre Box (1910), Oswald Birley. Private collection

‘Power & Beauty: The Art of Sir Oswald Birley’ is at Philip Mould & Co., until 10 October.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?