Inspired by ‘300 desenhos’ (300 drawings), a Brazilian project that launched at the start of May, ‘Dibujos por la Amazonía’ (Drawings for the Amazon) has sold works by 310 Peruvian artists to raise funds for Amazonian communities affected by the spread of Covid-19. In doing so, it has created both an archive of a moment of emergency and a snapshot of contemporary art in Peru.

Rember Yahuarcani is an artist from Pebas, a village in the Amazon (180 km downstream from Iquitos, in the direction of the border with Colombia and Brazil), who lives and works in Lima. On 15 March, when the Peruvian government declared a state of emergency and announced that a strict lockdown would start on the next day, he was visiting family in Pebas and was forced to stay there. Speaking on the phone after more than two months of lockdown, he says: ‘People are really scared of getting sick because there’s no real hospital here, only a care centre that doesn’t have the right equipment. The situation in Pebas is currently in stage three. The disease is in the village. The market has become a point of infection.’ To respond to the crisis, the Peruvian government established a distribution of vouchers to the most destitute, using banks as intermediaries. But the measure, which has been enforced throughout the country, is believed to have been a major vector of infection in the Amazon, where there are very few banks; people have had to travel to the main cities, queue for hours under the sun and the rain, and risk bringing back the disease to their communities.

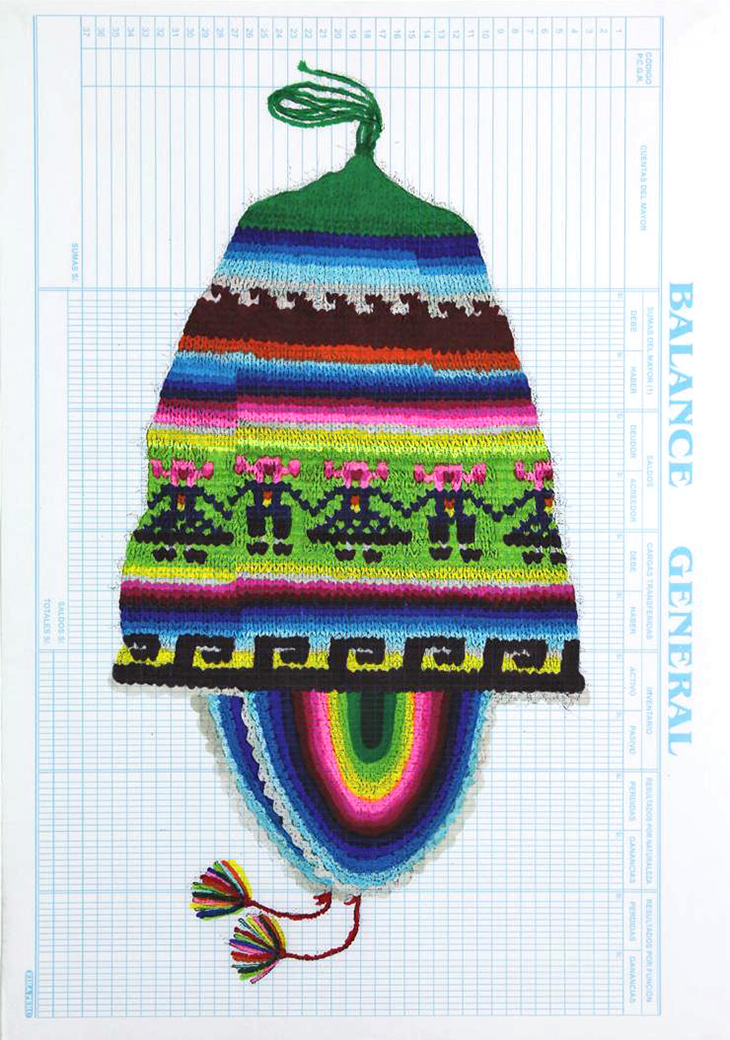

As soon as ‘300 desenhos’ launched, Miguel A. López, a Peruvian writer and curator based in Costa Rica, realised the project could be adapted to Peru. ‘Everything that’s happened now, with the country having completely collapsed, hadn’t happened, but you could see it coming. The spread was starting in indigenous communities and they were asking the government for help, which wasn’t coming quickly enough,’ he says. A team, most of them artists, quickly assembled around López and set to work. Artists had four days in which to send a drawing in A4 format. Four hundred and ninety artworks were donated, most of them made for the occasion. The website, which went live on 19 May, presents an ever-changing selection. For a donation of 150 US dollars people could acquire a randomly selected artwork, which could turn out to be by an established or emerging Peruvian artist. The artists taking part include Sandra Gamarra, whose paintings of people looking at famous artworks, or still lifes accompanied by a text, question how we look at art (she is also known for imagining a museum of contemporary art in Lima – a response to a lack of cultural institutions in the capital). Ximena Garrido-Lecca donated a work from the series ‘Una Gruesa de Chullos’, for which she scanned traditional Peruvian hats on to accountancy paper. López himself donated works from two important Peruvian artists: screenprints by the queer activist and drag queen Giuseppe Campuzano (1969–2013), which incorporate newspaper articles demonising trans people, and a drawing by Juan Javier Salazar (1955–2016), whose ironic conceptual work is still influential in the Peruvian art scene.

From the series ‘Una gruesa de chullos’ (2020), Ximena Garrido-Lecca. Courtesy Dibujos por la Amazonía; © the artist

According to López, ‘in the last two decades, Amazonian cultures have started to have an increasingly fluid dialogue with the city’. The curator says this was made possible by the end of years of internal conflict and dictatorship and by the internal migration of indigenous people from the Amazon to the city, where they became eloquent representatives of their communities, both culturally and politically. The wildfires in the Amazon forest in 2019 were another factor. ‘People started getting concerned, hoping there wouldn’t be more fires, and worrying about protected indigenous territories shrinking,’ artist Nancy La Rosa, one of the organisers of the project with López, says from Rio de Janeiro.

In Peru ‘the vice-ministry for interculturality’, a sub-department of the ministry of culture created in 2010, is responsible for indigenous people. The fundraising, Yahuarcani says, ‘was also a show of indignation from the Peruvian art world, [directed] not only at the vice-ministry for interculturality, but at the culture ministry in general,’ which, he says was incredibly slow to respond to the emergency. At the end of May, Peru’s culture minister resigned after paying a celebrity singer for motivational talks to ministry of culture personnel in the middle of the crisis. Yahuarcani says that the vice-minister for interculturality has lost the confidence of Peru’s main indigenous groups, who have called for her resignation. Meanwhile, Peru’s strict lockdown ignores the realities of a country where a majority of the labour force work in the informal economy. The country, which has long had one of Latin America’s lowest levels of public investment in healthcare, currently has the highest rate of Covid-19 infections in the region after Brazil.

Kené (2020), Olinda Silvano. Courtesy Dibujos por la Amazonía; © the artist

Despite having been severely sick with the coronavirus, Olinda Silvano, who is now recovering, took part in the project. She is one of the masters – who are generally women – of Kené, the design system of the Shipibo-Conibo people, and lives in Cantagallo, a shanty town close to the historical centre of Lima and the presidential palace. Cantagallo is home to a Shipibo-Conibo community and has had a high rate of Covid-19 infections. On a video that Silvano posted on Facebook she can be seen talking to the new culture minister who visited the shanty town: ‘Go to Ucayali, go to the Amazon, where there are big indigenous communities like us. […] They have no medicine, because they live far, no one goes there, and no one cares.’ With indigenous communities severely affected, the knowledge and experience that they share through their art has been endangered. ‘It’s an invaluable memory, millenary, transmitted from generation to generation through oral memory, paintings, fabrics, drawings, and we’re at risk of losing all of this,’ López says.

Christian Bendayán, a painter and curator who was born in Iquitos and lives in Lima, is the best-known ambassador for Amazonian art, having represented Peru at the Venice Biennale in 2019. He also curated a selection of Amazonian art for the Peruvian trade pavilion in Moscow during the FIFA World Cup in 2018. He explains that the three organisations ‘300 desenhos’ is helping, the Iquitos Vicariate, Radio Ucamara (an indigenous radio station located in Nauta), and the Shipibo governing council (COSHIKOX) in Ucayali, are involved in three different parts of the Peruvian Amazon. López says, ‘We understood quickly that the project would work if communities could see themselves represented in the organisations we were supporting and if it was very transparent. We put a lot of effort into meeting the right people and the right organisations so that the money could be used effectively, and reach people, because the government has been very criticised for failing to do that.’

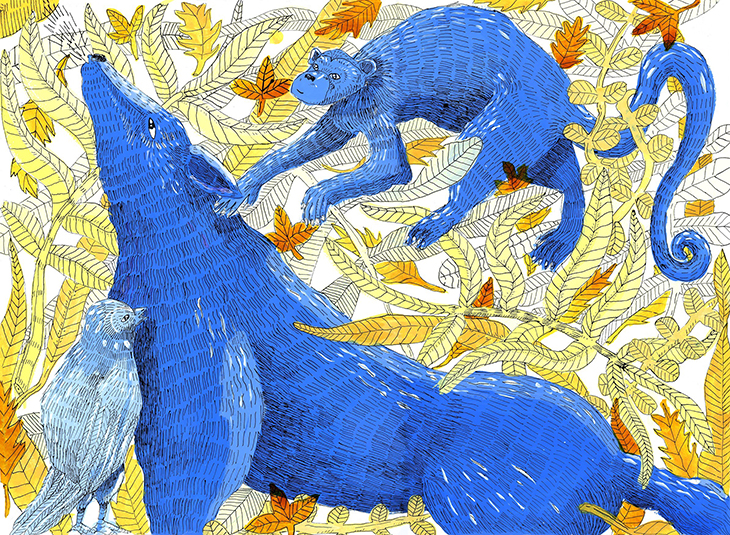

Animales Azules (Blue Animals) (2020), Lucia Coz. Courtesy Dibujos por la Amazonía; © the artist

Yahuarcani, who also donated work, resists the label ‘indigenous artist’. ‘In a country like Peru,’ he says, ‘this is a label that carries a lot of social discrimination. You wouldn’t say that this artist from Lima or Arequipa is a “Limeño” or an “Arequipeño” artist. I think that if we could exhibit work by an indigenous artist next to work by an artist who comes out of art school, it could help see the indigenous world differently, in a way that is more horizontal.’

According to Bendayán, artists from the Amazon, even those who have represented Peru in international exhibitions and art fairs, haven’t had the same opportunities to have their work shown and their voices heard. They have also often been paid less, possibly on the assumption they were artisans rather than artists. Bendayán says: ‘This need for inclusion goes beyond art, of course. Despite the fact that the Amazon represents two-thirds of Peru’s territory, we’ve only recently discovered that we were an Amazonian country.’

Indigenous Amazonian art may also open up different perspectives. Artist Eliana Otta, who runs the platform Bisagra in Lima with López and others, says: ‘The Amazonian view of the cosmos offers us the possibility of a necessary paradigm shift […] it’s an art that takes us away from the notion of an individual genius alone in his studio and can make us explore creation in community.’

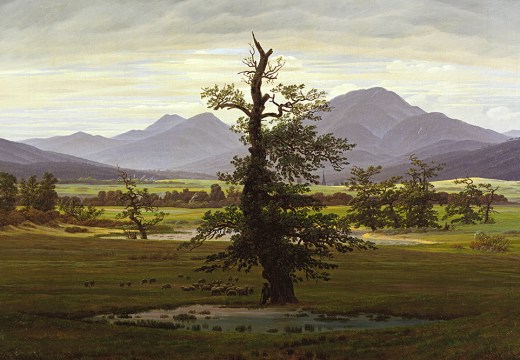

Untitled (from the series ‘Selva para mañana’) (2020), Christians Luna. Courtesy Dibujos por la Amazonía; © the artist

One drawing by Christians Luna presents two silhouettes wearing the clothes of an Amazonian tribe. Two speech bubbles come out of their mouth and say ‘Mañana’ (tomorrow). López confirmed this was an indirect quote from what is possibly Juan Javier Salazar’s best known work, Perú, país del mañana, proyecto para hacer un mural cuando tenga el dinero, mañana (‘Peru, land of tomorrow, project for a mural when I have the money, tomorrow’), which shows a series of Peruvian presidents saying ‘Mañana’. ‘It recontextualises,’ López says, ‘in the body and the voice of indigenous communities, this irony of Juan Javier, this idea of a tomorrow that never comes, of a country that is a promise that never becomes a reality.

More information about the project is available at ‘Dibujos por la Amazonía’.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?