Jane and Louise Wilson are drawn to the structures of dystopian modernity, to sites of power and experimentation that have fallen into obsolescence. For their latest work, Undead Sun (commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella for the Imperial War Museum to commemorate the centenary of the First World War) they turned to Farnborough’s Wind Tunnels, which were built at the beginning of the 20th century to study aerodynamics. In this extraordinary setting, the artists staged a sequence of scenes that – combined with animation, photographs and storytelling – suggest the technological complexity, devastating effects and ethical predicaments of modern warfare.

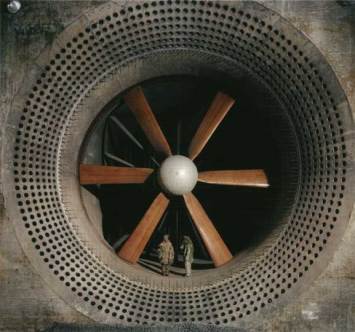

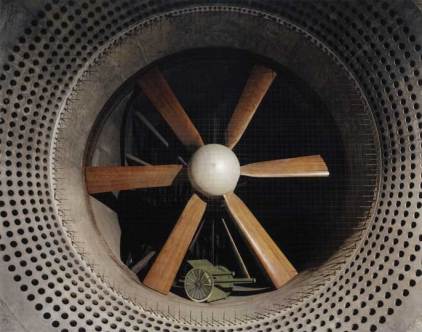

Undead Sun explores the First World War’s nascent mechanics of propaganda, aerial warfare and camouflage, playing with perception and deception. Toy-like decoys are propped against the ominous mouth of the tunnel. Soldiers team up to rotate the blades of the turbine while others build an intricate wooden structure, its function unspecified. Painted sheets stand in for rail tracks, and the carcass of a horse, by which a seemingly dead soldier is sprawled, turns out to be a sniper’s nest. The control of the gaze is implicit throughout the film and its narration, but also in the Imperial War Museum’s installation. The artists have built gauze fins based on the blades of Farnborough’s turbine: they channel the viewer’s experience, allowing access to the screen from several points while obstructing vision from others.

It is one of the great paradoxes of war that destruction also brings progress, be it in engineering or medicine. In 1914, Germany was leading in the field of optics and surveillance, and the film features a German aerial camera from the museum’s collection. The violence of its gaze is emphasised by the camera’s design: its handle is based on the shape of a gun, to make it easier to operate in flight. The film also includes First World War photographs by Horace Nicholls that show the sculptor Francis Derwent Wood fitting prosthetics to the face of a disfigured soldier: the war engendered horrific mutilations but also triggered the development of reconstructive plastic surgery. The sequence lingers on the disturbing sight of a fragmentary facial plate lying on a table, its eye staring out of the frame.

The Wilsons are keen to point out the peculiarity of two women working together on forgotten sites of a distinctly masculine nature, and it is perhaps with this in mind that they chose a female voice to narrate their film. The duality does not end there, for the voice is that of a German woman, performing words borrowed from Tom McCarthy’s novel C (2010). Blending early 20th-century communication, aviation, war and mal de vivre, the book is described by the Wilsons as ‘epic, graphic and visceral, filmic and poetic’.

‘Underground you can only hide if you are able to imagine the view of yourself from above’, ‘the elimination of the shadow is the essence of invisibility’, the voice recites in a hauntingly melodious litany. ‘Kennscht mi noch?’ she asks in Swabian, ‘Do you still recognise me?’, conjuring the sight of these words on the wings of deadly German planes, and the disfigured soldiers, who lost their identity along with their facial features.

There is courage to be found in battle, but refusing to fight is no less brave. The last sequence in the film evokes First World War conscientious objectors and, closer to us, US veterans from the Iraq wars. A man undresses, methodically shredding his uniform. He hangs the torn pieces on barbed wire, with a controlled anger and deliberateness that is heart-rending. Stark naked, he walks away, out of breath, having recovered his dignity in this act of rebellion against a conflict he does not condone.

Poignantly, the title Undead Sun is inspired by Abel Gance’s film J’accuse. It relates to the Ode to the Sun written by its main protagonist, the poet Jean Diaz (and his final cry to the sun for being complicit to the horror of war), and the unforgettable apparition of soldiers rising from the dead. Shot between the last months of the war and 1919, the film denounced the brutality and futility of conflict. Jane and Louise Wilson reflect that the terrible mechanics of modern warfare, as we know them today, were born a century ago. And Gance’s accusation remains, sadly, valid today.

‘IWM Contemporary: Jane and Louise Wilson, Undead Sun‘ is at the Imperial War Museum until 11 January 2015.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?