In Tate Modern’s joyous exhibition ‘Matisse: The Cut-Outs’, swallows dive, sharks stalk, coffee pots steam and acrobats leap: all caught with an incisive snip of Henri Matisse’s dressmaking scissors.

‘Large Composition with Masks’ (1953), Henri Matisse, © National Gallery of Art, Washington © Succession Henri Matisse/DACS 2013

Made in the last 17 years of Matisse’s life, from 1937 to his death in 1954, these works are vital, energetic and youthful. At the age of 71 Matisse underwent surgery that left him wheelchair-bound. No longer able to paint, he began experimenting with cut-outs as a way of playing with composition. He would cut straight into coloured paper: yellow, pink, teal, purple, blue, orange and black.

It was when making the book Jazz (1943–6) that instead of a means to an end, Matisse began to see cut-outs as works in their own right. Commissioned by arts publisher Tériade, the book is illustrated by 20 Matisse cut-outs depicting members of the circus. Knife throwers, sword swallowers, swimmers, trapeze artists, clowns and elephants explode from the page.

‘Icarus’ (1946), Henri Matisse, © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Claude Planchet © Succession Henri Matisse/DACS 2013

In Icarus (1943), the ill-fated mythical character tumbles through a royal blue sky studded with stars, a ruby red spot covering his heart. Made in the context of the Second World War, could the stars be explosions, the red mark a bullet hole, the falling silhouetted figure, a corpse?

Oceania, the sky (1946) and Oceania, the sea (1946) are inspired by Matisse’s 1930–1 trip to Tahiti. Assorted marine forms float, cut from white paper on a taupe background. When first made, these delicate cut shapes were not glued to the studio wall, but were pinned where they would ripple like the ocean in the balmy Vence summer breeze.

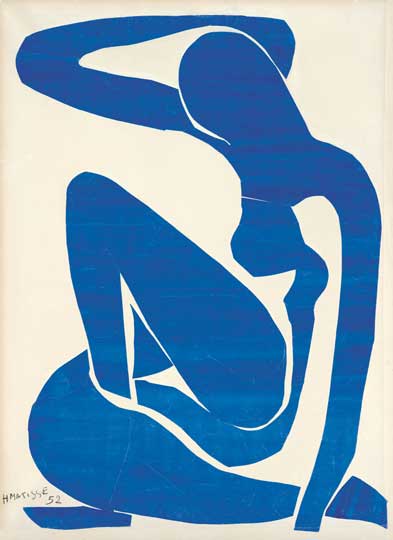

‘Blue Nude (I)’ (1952), Henri Matisse, Photo: Robert Bayer, Basel © Succession Henri Matisse/DACS 2013

Four Blue Nudes are displayed together, complemented by bronze, chunky, modernist sculptures from the early 1930s. It is fascinating to note that in one composition, Blue Nude IV, Matisse used multiple different pieces of blue paper stuck together to get the shape correct: a thigh is widened, a foot altered, a knee patched. The other three, by contrast, are each made from a single cut of blue paper, sleek, sculptural and confident.

It is great to see artworks that are so often reproduced, in the flesh: their scale is stunning. The Parakeet and the Mermaid (1952), covers an entire wall with sharp slices of colour. The Snail (1953) is moving in its urgency. Completed the year before Matisse’s death, chunks of colour seem hastily collaged together – as though Matisse realised there wasn’t much time left.

These late works are brimming with life, colour and vitality. They are also ahead of their time. ‘It seems to me I am anticipating things to come,’ Matisse said. ‘It will only be much later that people will realise to what extent the work I am doing is a step in the future.’

‘Matisse: The Cut-Outs’ is at Tate Modern until 7 September 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?