From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

This magazine’s first home, as the cover of its maiden issue in 1925 announces, was 6 Robert Street, Adelphi. For a new journal taking the classical god of the arts as its namesake, this could hardly have been a more suitable address. The Adelphi was an area of London between the Strand and the River Thames that had been developed between 1768 and 1774 by the most fashionable neoclassical architect of the day, Robert Adam – or ‘Bob the Roman’, as he called himself. And while the ambitious Scot had already applied much of what he had absorbed on his Grand Tour to some of Britain’s great houses – at Kedleston, Syon, Osterley, an Englishman’s home was now his Roman palace – nowhere, arguably, did he evoke a particular classical structure more entirely than at the Adelphi.

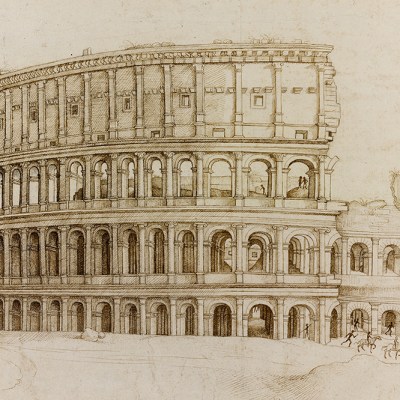

Adam had travelled to Italy in 1755, spending the best part of two years in a landscape rich in ancient ornament but crowded with competitors. Perhaps it was his particular admiration for the Baths of Diocletian in Rome that provided some of the motivation to seek out Spalatro, modern-day Split in Croatia, where that emperor had retired in 305 AD ‘to plant cabbages’. The Dalmatian coast was beyond the usual Grand Tour itinerary, and the ruins of the waterfront palace that Diocletian had built there had never been surveyed.

In 1757 Adam returned home with a precious trunkful of drawings from Italy and his ‘jaunt to Dalmatia’ – where he and his fellow draughtsman Charles-Louis Clérisseau had been asked to leave by the Venetian authorities, who in the climate of the Seven Years’ War took their surveying activities for espionage. Adam had gathered enough material, however – including a new ‘Spalatro’ order – to inaugurate in Britain a style, as he put it, ‘directed but not cramped by antiquity’.

A decade later, Adam’s career, boosted by grand commissions from the British aristocracy, was at its zenith. He had published his impressive monograph on the ruins of Spalatro in 1764. Despite his achievements, however, state commissions were not forthcoming, and he was excluded from membership of the newly established Royal Academy of Arts (William Chambers, the king’s favoured architect, may have had something to do with it). In 1768 Adam’s typically bold response was to lay the foundations, literally, for his own speculative housing scheme, to be built with his three brothers. Its name, Adelphi (ancient Greek for ‘brothers’), and those of its streets – Robert, John, Adam – would leave no one in doubt of its origins. The site the enterprising siblings had identified was a dilapidated area sloping down to the Thames known as Durham Yard – in previous centuries occupied by a splendid house belonging to the Bishop of Durham, but now regularly flooded by the sewage-infused tidal river. On this 14,000 sqm plot Adam planned five streets of elegant housing, including a monumental principal block running along the river. This ‘Royal Terrace’ (later known as Adelphi Terrace) would be built up on a podium of arched vaults – a necessary practical measure to correct the site’s steep incline and secure the buildings from flooding; but also making the visual echoes of Diocletian’s palatial waterfront structure, with its cryptoporticus, hard to ignore.

Plate from Ruins of the palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro (1764), Robert Adam (1728–92). Royal Collection Trust. Photo: © Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd 2025 | Royal Collection Trust

Through a combination of bad luck and arrogance, the Adams quickly ran into financial difficulty. While cost-cutting attempts were rumoured to include drafting in cheaper workers from Scotland – their labour accompanied by bagpipes to boost morale – what saved the project (if not, ultimately, the Adams’ solvency) was the organising in 1773 of a public lottery. Properties still unsold in the Adelphi were among the main prizes, for which 4,370 tickets were issued at £50 each.

Already enjoying their occupancy at Number 5 Royal Terrace, one of the first houses to be completed, were David Garrick and his wife. The actor and impresario was a friend of Adam’s, and had moved in in March 1772 when much of the development was still a building site. The spectacular ceiling Adam designed for his drawing room – all birthday-cake colours and plaster festoons (or ‘Gingerbread and snippets of embroidery’, as Horace Walpole sniped) – is now in the V&A. At its centre is a roundel depicting Apollo with his horses, probably painted by Antonio Zucchi, who worked on many Adam projects (as did his wife, Angelica Kauffman). Surviving Chippendale accounts attest to the fact that Garrick commissioned furnishings to match the splendour of Adam’s interiors – and that, like his architect friend, he rather overreached himself.

If Garrick ran out of sugar or witty company he could call on Topham Beauclerk, great-grandson of Charles II and Nell Gwynne and his neighbour at no. 3. Robert and James Adam themselves occupied no. 4, before moving on to 3 Robert Street. Their place in Royal Terrace was taken by ‘doctor’ James Graham, who installed his famous ‘celestial bed’ there, which promised to deliver, by means of electrical pulses, heightened sexual pleasure and fertility. One wonders how he got on with the likes of the 3rd Earl of Effingham, deputy Earl Marshal of England, who was the first occupant at no. 10.

By 1850, when David Copperfield was published, the Adelphi had clearly shifted from a highly desirable area to something less salubrious. Dickens has his hero lodging in nearby Buckingham Street, where the writer himself lived in 1834, and recalling of the time: ‘I was fond of wandering about the Adelphi, because it was a mysterious place, with those dark arches.’ Later that century Adam’s Royal Terrace facade was Victorianised, and the building’s fate sealed in 1864 with the construction of Victoria Embankment. The Adelphi was no longer a waterfront palace.

Current view of the only building that remains of Adelphi Terrace, the furthest house to the left in original views from the river. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Apollo’s tenancy on Robert Street was relatively short-lived. By 1933 the magazine had moved to Chancery Lane, three years before most of Adam’s Adelphi was demolished. In its place, the architectural firm Collcutt & Hamp summoned New York and Chicago with a brawny art deco office building. Yet its mystical atmosphere seems to have lingered. Like Copperfield, the protagonist of E.M. Delafield’s diaristic Provincial Lady in Wartime (1940) also lodges in Buckingham Street, finding herself drawn to an ARP station in ‘Adelphi underworld’: ‘Descend lower and lower down concrete-paved slope – classical parallel here with Proserpina’s excursion into Kingdom of Pluto – and emerge under huge vaults full of ambulances ranged in rows.’ Sections of Adam’s streets with their plaster griffins and pilasters of scrolling vegetation do remain, the elegant headquarters that he designed for the Royal Society of Arts chief among them. Its subterranean red-brick vaults are readily suggestive of encounters with the ghosts of Adam or Garrick. Or even, perhaps, of Diocletian.

From the June 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.