The California-based artist Sam Contis talks to Fatema Ahmed about ‘Day Sleeper’, her recently published book of photographs from Dorothea Lange’s extensive archive, and about her first book, a photographic study of life and the landscape at Deep Springs, a single-sex liberal-arts college near the Sierra Nevada.

Dorothea Lange’s personal archive of about 40,000 negatives and a few thousand prints is at the Oakland Museum of California. What led you to the archive, and how did this book come about?

I moved to California in late 2012 – I live in Oakland – but it wasn’t until the summer of 2017 when I saw that the Oakland Museum of California was doing an exhibition on Dorothea Lange. I’ve long loved Dorothea Lange, so I went to the show and discovered that they [the museum] were the keepers of her personal archive. I was simply curious what that meant, and so I emailed and made an appointment […], with no project in mind other than to satisfy my own curiosity, and it was there that I saw pictures of hers that I had never seen before and that I was really excited about.

I had no idea that when Lange first moved to California in the first few years she opened a studio and really spent the first decade of her career as a portraitist. There were beautiful pictures of her family that I had never seen before, and hand studies of her first husband, Maynard Dixon, who was a painter. I think I had had a very limited view in terms of not realising that the government work really spans a short period of time in her life. For example, the FSA [Farm Security Administration] photographs are only four or five years of work. I was excited to find an artist in the archives who was new to me.

Dorothea Lange, from ‘Day Sleeper’ by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis. Courtesy of MACK and the National Archives, Washington, D.C.

The only reason I know that the archive is in Oakland is because the museum organised a show that travelled to the Barbican here in London and then went to the Jeu de Paume in Paris. The title of that exhibition was ‘Politics of Seeing’. It was a big show, but what’s so interesting about your book is that it presents not a different photographer, but images made in very different circumstances. When did you know that you wanted to put them in a book?

I was going home from the archive and telling friends and other photographers, ‘I just saw the most beautiful Dorothea Lange pictures that I’ve never seen before’. I had wished there would be a book of these pictures, but it wasn’t immediately obvious that I would be the one to do it. Then I started talking to Sarah Meister, the curator of the exhibition that’s on right now at the Museum of Modern Art in New York [until 19 September], and they’re doing a different sort of Dorothea Lange show from the Jeu de Paume/Barbican show, one that focuses on works from MoMA’s collection. It was through those conversations that the book came about; book-making is an important part of my practice, and that felt the natural way to allow other people to see a lot of this work.

You used the word ‘beautiful’, and that’s a really striking aspect of some of the pictures. They’re also surprising. One of the things that Dorothea Lange does, and maybe you do it in some of your work, is that she can make bodies quite sculptural or parts of bodies quite sculptural, and then make inanimate things look full of life.

I think that’s where I saw a strong kinship or correlation between the way we work, the way we approach the world photographically – the ways that the landscape or these inanimate objects can look like the body and the body can have this sense of the landscape in it. That really struck me and – just to go back to your note about the ‘Politics of Seeing’ show – one thing I wanted to emphasise in the book is to look at these more personal pictures, for example the family pictures, next to work that’s more overtly political or work that was made on assignment for the government; to have those kinds of images more strongly co-exist together, to get rid of chronologies and to allow the images to be removed from their original context and have these new relationships emerge. There’s the same artist in all of these kinds of pictures – just because you’re on assignment doesn’t mean you’re suddenly going to look at the world differently. […] So I’m glad you’re seeing trees become bodies – or the veins, for example, in a pair of hands start to look like trees.

Dorothea Lange, from ‘Day Sleeper’ by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis. Courtesy of MACK and the National Archives, Washington, D.C.

Dorothea Lange once said that she’d learned to move in a certain way so that people wouldn’t look at her when she was doing a lot of her work. I wonder whether you noticed anything particular about how she was working.

It’s very physical making photographs, and she was quite a small woman and had suffered polio as a child. I think even the way she moved as a result of polio changed her relationship to the world dramatically, and the way she was just able to move physically through it. In spite of that she often carried three cameras. She would have two large-formats and a medium-format camera – and this is very heavy, laborious equipment.

I’m somebody who also works with a handheld camera and a large-format camera, which fits on a tripod; and you can see in some sequences of images when she’s working with a camera on a tripod – a large-format camera where she’ll put the camera down in one place and stay at a distance where she’s able to observe. That’s the interesting thing with a large-format camera, you can’t not be seen. There’s no way to remain invisible, but there is a way to allow yourself to become part of the scenery and, over time, if you set up and allow people to get used to your presence, then when you move through it with a bulky camera people don’t notice you as much.

I saw her sort of starting at more of a distance, seeing exactly what she was interested in but then slowly moving closer and taking a few photographs along the way. It almost felt like a warm-up exercise, a conversation with the subject as she slowly got closer to what it seemed like she was interested in all along.

Dorothea Lange, from ‘Day Sleeper’ by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Courtesy MACK

Are there any images that you were particularly pleased to have found or were surprised by?

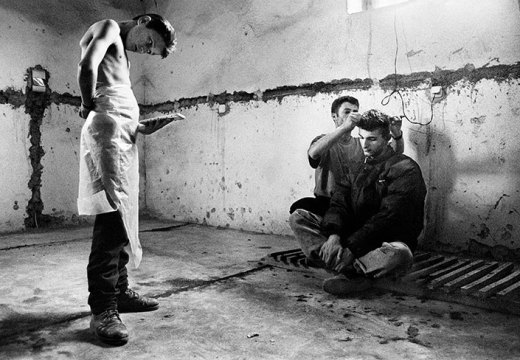

There are some beautiful portraits. She was known for her portraits but, for example, there’s a portrait of a young girl where she’s raised her hand to her mouth and she’s giving the camera quite a provocative look. I was floored when I saw that picture. Every time I encounter it, I feel like I’m stopped in my tracks. There’s also this beautiful, tender little photograph where she’s photographing her daughter-in-law cutting her son’s hair.

The book focuses on California, so when I was talking about the personal and political, this is all in the state that she’s made her home, where she’s living and working, and a lot of the pictures in the book aren’t very far from her house. There is a picture that I really love of a man in a coverall suit wearing a hat and these dark glasses. He’s working in a port in Richmond, which is actually right next to Berkeley, so again that’s definitely a picture that was made a few miles from her house.

You write in your afterword that she seems to be very interested in hands.

There is a passage that I’ve included in the notes of the book, where she talks about an early childhood experience. I think a lot of artists, or a lot of visual artists, have these profound visual experiences early on, and in some ways the work you make is a constant reflection of that. She talked about as a child going to church with her mother, because her mother was interested in listening to the music. She was too small to see the musicians, but what she does remember is above the church crowd the hands of the conductor waving wildly. In a way I feel like she’s seeing those conductor’s hands for the rest of her life – but with her interest in labour, too, the hands are a great reflection in some ways, even more than a face, of a person.

Dorothea Lange, from Day Sleeper by Dorothea Lange and Sam Contis. Courtesy MACK

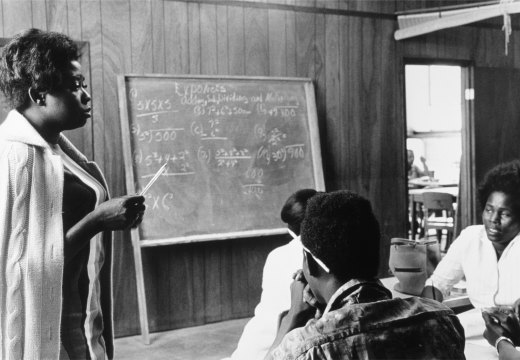

If we come to your own work, can you tell me how you got interested in Deep Springs, the subject of your first book? For readers who don’t know it, it’s a tiny liberal-arts college in California on a cattle ranch. It’s still an unusual college, but it was even more unusual when you were taking photographs there…

It had been single-sex for 100 years and has just recently gone co-ed. Initially when I heard it was going to go co-ed, that set up my desire to approach it as a place, but it was a place that I had heard about probably five or six years before I started making pictures there. I think my interest in it was a larger interest in the West and thinking about how the West has been gendered.

We’ve seen certain depictions of masculinity in the visual culture of the West and there’s a long photographic history, too. I’m interested in pushing back against certain established views, whether it’s around a single person or maybe a larger culture. I was interested in the myth of the American West and the iconography that has emerged through that mythology and had come, in my eyes, to be a sort of dominant visual reference for the West – particularly as I had recently moved to California, and as a woman trying to think about my place within that larger history of the West, and even just in terms of that photographic history, I was interested in asking questions around what it meant to be a woman making work in this landscape. That physical space, the college and Deep Springs Valley gave me a place to explore those ideas.

When I approached [Deep Springs] I thought perhaps I might only have, say, a year to make the work, that it might go co-ed more quickly. But then I ended up spending almost five years there – it was a long, drawn-out process for them to go through – but I was happy to have a longer period of time to explore. I wanted to explore what it actually felt like to stay in this space and see the landscape change over seasons, and work with the young men who were students there over longer periods of time.

There are two strands in the book that speak to each other really well – you combine archive photographs with your own pictures. Were the old photos of Deep Springs and the landscape part of the plan from the beginning, or were they something you came across once you were there?

I had no idea those images existed until I had actually visited a couple of times. Most of those pictures come from old personal photo albums that have been given back to the school [for its] archive. The pictures weren’t meant to service an official document in any way, but they were made as personal pictures by some of the first students at the college. I was really interested in looking at how they were looking at themselves at that time and how a lot of them were coming to this place, like me, from somewhere else. They weren’t native Californians necessarily, and so what it meant to find themselves in this landscape and what it meant to use photography – for them it was a new tool, and I was really struck by the way they were using it.

The college is a very physical place – the students farm, they look after animals – but your pictures are very gentle in many ways and the people seem very comfortable being looked at. There are hardly any with people who are looking directly at you – and then there are some extraordinary ones, like the guy who’s sprawled out reading on a sofa or a bed, and he’s naked. How did you get to that level of closeness without them being fussed about your presence?

That picture that you mention, that felt like a dialogue with the young man in that picture and it was made after I’d known him for a couple of years. I wanted to feel, in a way like I described Dorothea Lange slowly moving through the landscape, I wanted to get to the point where I was just there, like a piece of furniture, or a tree in the landscape, but we could interact as much as they or I wanted to. That sort of relationship, I think, develops over time. I wouldn’t just drop in for a day or two – it’s actually quite far from my house, and in some weather it’s a nine-hour drive, so I would go for weeks at a time. It’s a very close-knit community and so it was important for everybody, including myself, to feel really comfortable.

You talked about being interested in ideas of the West, which are almost created by our collective image banks. There’s also a domesticity in the pictures because of the tasks that people are doing and have to do, so it seems very masculine but also very pastoral.

It’s not necessarily an all-male community – it’s an all-male college, but there are women present like professors; for a long time the ranch manager was a woman. But because it’s a work college the young men are asked to do different kinds of tasks, ones that might traditionally be gendered as more feminine tasks and some that might be more traditionally gendered as masculine tasks, and they do both. They’re milking the cow, they’re hanging the laundry, they’re cooking for each other. They’re also raising and butchering animals, they’re collecting eggs. […] I really wanted to reveal the fluidity in the work that they did in that environment.

With the archival photos, do you think people had images in their head that they were responding to? Were they deciding to frame something in a certain way because of something they’d seen, or is it much fresher than that?

I think they probably had certain images in their minds. There was a lot of painting of the West, and they were there in the early 20th century – they started to take pictures in the teens and early 20s and in the few decades before that – but photography was invented around the time that new settlers in America started migrating westward. Photography really was used as a tool to sell a certain version of the West to get people to move west and to get these settlers to come […] to sell as an idea of Come West, start over, reinvent yourself. That idea of the West has always been synonymous with photography because it came into being at the same time.

Practically, most of your photographs are black-and-white, but there are a few colour images. What kind of choices were you making both when it came to taking them and including them?

Originally, I wasn’t sure what my photographic approach would be in this place, so I wanted to keep an open mind and approach it more experimentally. I was working with different kinds of cameras, different formats of cameras, and different films, black-and-white, colour; I was also using digital cameras. Initially I thought I would choose one to tie it all together, and then I realised pretty quickly that what was interesting to me was working in different ways and making different kinds of pictures, from landscapes to portraits and maybe closer studies. But then having this multitude of formats, and colour and black-and-white, and then when the archival pictures came into the mix – they’re technically black-and-white photos but they have a certain patina of time and the time has a colour to it – that also became a helpful way of linking the black-and-white and colour in my mind.

I wanted to be able to speak out in these different registers or languages and I felt like the colour was really important. It was really important, for example, if you see the red blood on a sheet that came after a slaughter and to see the colours of the land, the colours of the flesh. But the black-and-white images were equally important as a way of referring to the history and the way we see this landscape, and blurring the lines in a way between the past and the present.

Day Sleeper: Dorothea Lange – Sam Contis and Deep Springs: Sam Contis are both published by Mack.

‘Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures’ runs at MoMA until 19 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?