Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532/33–1625) is widely credited as the first female artist of the Italian Renaissance. Born into a Cremonese family of middling social status, she was extraordinarily long-lived. In early adulthood she corresponded with Michelangelo and in 1624, when probably in her late eighties, she was visited at home in Palermo by Van Dyck. By then, she had long been renowned as a marvel of her sex – a gifted and successful artist, who had been employed by the Spanish crown – but also as a great beauty. Several men, Michael Cole tells us, fell in love with the wide eyes and luminous skin that glow from the numerous self-portraits with which she made her name. In these early works, Sofonisba portrayed herself engaged in learned pursuits: at the easel, reading, playing a keyboard instrument. In each, her attire is modest and sober: a simple black gown over a high-collared white lace shirt, befitting an unmarried young woman (she regularly signed herself virgo). Several decades of feminist scholarship have argued that in adopting this mode of self-portraiture, Sofonisba asked viewers to focus not on her body and her beauty, but on her talent, her skill, her accomplishments. Yet when Van Dyck sketched the artist in late life, by then blind and hunched, he noted her instructions ‘not to place the light too high, such that the shadows in the wrinkles of the aged face become too large’. Was this vanity from a fabled beauty who, as Cole explains, had pointedly contrasted female youth and old age in drawings of the 1550s? Or was it a repudiation of tenebrism and the exaggerated wrinkles favoured by its leading proponent, Caravaggio? The latter is certainly possible, given that Sofonisba practised a neat and decorous manner of painting, described by Vasari as done with diligenza.

The first dictionary of Italian, the Vocabolario della Crusca (1612), defines diligenza as ‘exquisite and assiduous care’, which fits Cole’s book as much as it does Sofonisba’s painting. For above all, his important monograph is an exemplary exercise in cautious, balanced scholarship. This is necessary on several counts. First, because Sofonisba – a controversial figure – has given rise to much speculation and exaggeration in the secondary literature. Cole’s treatment of that body of work is scrupulously polite, but it is evident his book is intended as a measured rejoinder to some of the excesses of previous accounts. One of its most significant parts is the catalogue organised into four sections: ‘Documented works/works with uncontested signatures’; ‘Attributions largely accepted by specialists’; ‘Works with contested or insufficiently discussed attributions’; and ‘Works attributed to Sofonisba but accepted by few specialists’. There is a worryingly large number of pictures in the latter two sections, a strikingly small number in the first two. Into the ‘largely accepted’ group, Cole puts one of the best-known works in the corpus: Sofonisba’s teacher, Bernardino Campi, at the easel, painting his famous pupil. It is regarded by some as a statement by Sofonisba about her own artistic identity, but Cole persuasively argues (reviving Robert Wiler’s suggestion) that it was probably painted by Campi himself. If this is correct, it suggests that the eclipsed teacher sought to claim: ‘I made her what she is.’

Self-portrait at the Easel (c. 1556), Sofonisba Anguissola. Lancut Castle Museum. Photo: Maria Szewczuk

Cole pivots away from the ‘singularity’ model of Renaissance artistic achievement dominant since Burckhardt’s The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy towards Sofonisba’s relationships: with Campi, with her siblings, with her own pupils, and above all with her father, Amilcare. The latter is the subject of the first chapter, in which Cole interprets Sofonisba’s early career as guided above all by a father-daughter relationship. Where most men of his class would have sought an advantageous match for their daughter, Amilcare instead sought family honour through his child’s skill, at a time when painting (at least in Italy) was increasingly valued as intellectual and liberal. Cole reads a fascinating self-portrait of c. 1556 in this light, proposing that the cypher on the tondo Sofonisba holds spells ‘Amilcare’. Sofonisba thus bears her father’s name like a coat of arms – the tondo is a clipeus, a heraldic shield. It may also, Cole suggests, be considered a mirror. If, as seems plausible, Sofonisba painted this small and intimate work for her father, he would have seen his own likeness reflected both in his offspring’s face and in a shining disc that bears his name.

Self-portrait (c. 1556), Sofonisba Anguissola. Photo: © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

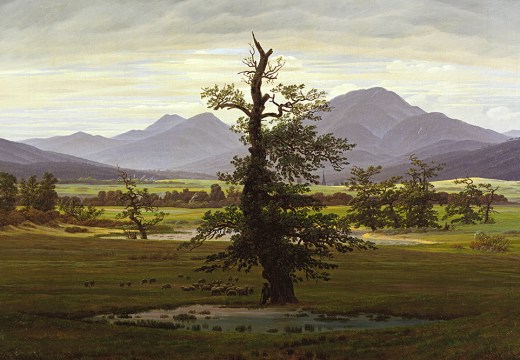

Amilcare’s ‘absent presence’ is felt equally in Sofonisba’s most famous work: The Chess Game (1555). This highly original and early example of a ‘conversation piece’ depicts the painter’s sisters Lucia, Minerva and Europa in the middle of a game, watched over by a servant. Sofonisba has signed herself present in an inscription on the chessboard’s edge: ‘by the maiden Sephonisba Angussola [sic], daughter of Amilcare, painted from the true effigies of three of her sisters and of her maidservant, 1555’. The scene takes place against the backdrop of a prominent oak tree (Amilcare), while the three rooks visible on the chessboard are fashioned as acorns (the Anguissola sisters). Given that Sofonisba emphasised the learned aspects of her craft, might this not allude to an Aristotelian commonplace about formal cause: ‘the acorn is happy to become an oak’? With proper nurturing, Amilcare’s offspring will, like the acorns fallen from his wide branches, grow to become sturdy oaks in their own right. There is no escaping the paternalism of this interpretation. But that doesn’t necessarily make it wrong. Cole (as his acknowledgments indicate, writing both as a teacher and as a father of a daughter) concludes his introduction by observing: ‘Four decades of literature have taught Renaissance scholars to ask whether Sofonisba was a feminist. But they can also ask the same of her father, her teacher, and her king.’ Cole’s book carefully and with historical rigour suggests what a 16th-century feminist might have looked like, while offering a compelling example of feminist art history for the present day.

The Chess Game (1555), Sofonisba Anguissola. National Museum, Poznan

Sofonisba’s Lesson: A Renaissance Artist and Her Work by Michael W. Cole is published by Princeton University Press.

From the June 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?