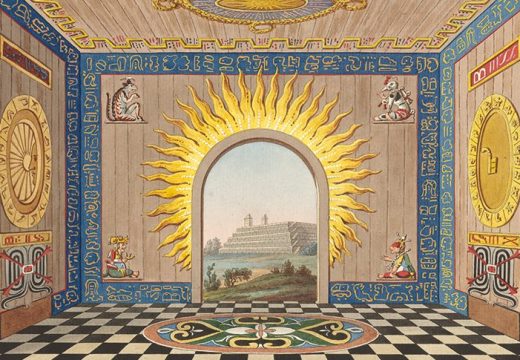

Thanks to the work of scholars such as Clive Wainwright, when we think of the early 19th-century historic interior, we tend to think of antiquarianism and the Gothic Revival. In her brilliantly original new book, Diana Davis reminds us that the British elites were just as enthralled by the magnificence of what they called, anachronistically, ‘Louis XIV’ style. A baggy shorthand for everything from boulle (or ‘buhl’) tables to pietre dure cabinets, bronze-mounted Chinese porcelain, Gobelins tapestries or furniture attributed, misleadingly, to Jean-Henri Riesener (or ‘Reisner’), the so-called Louis XIV style signified ‘stylistic promiscuity’. This aesthetic had little to do with the Sun King, or with an accurate reproduction of French interiors. Rather it was a British creation, an inventive hybrid of old and new that Davis christens ‘Anglo-Gallic’.

Dealers, rather than patrons, were the real pioneers in forging and disseminating the style, acting at once as art advisers, canny retailers, interior designers and skilled craftsmen. In France, this blurring of competences was brought about by the Revolutionary abolition of the guilds in 1791, which swept away the old divisions between the retail and manufacture of luxury goods by the marchands merciers. In Britain, dealers seized on the glut of porcelain, gilt bronze, furniture and architectural fragments which could be acquired cheaply across the Channel and which, with some modification, could then be imported into the homes of wealthy clients. Advertising his range of services, Samson Wertheimer described himself as ‘curiosity dealer & ormolu factor’. Davis documents the buzz that grew up around the auction of French goods in early 19th-century London, and the West End shops that purveyed these ‘French elegancies’.

George IV (1762–1830) (1821), Thomas Lawrence. Royal Collection Trust/© HM Queen Elizabeth II 2020

Tastemakers profiles not only the more celebrated figures and monuments in this revival, such as the Duke of Buccleuch and Lord Hertford, or Carlton House and Hamilton Palace, but also the middlemen who assimilated French art for British tastes. These included the importers of French goods, such as Robert Fogg and John Boykett Jarman; French dealers and artisans in London, such as Féréol Bonnemaison and Alexis Decaix; not to mention Rudolph Ackermann, who printed crude anti-Napoleonic caricatures but also promoted French furnishings in his publication the Repository of Arts. The contribution of dozens of such individuals is recorded in an extremely useful appendix. Davis explains how, despite decades of warfare and blockade, the British aristocracy continued to admire the refinement of French decorative arts and, whenever possible, crossed the Channel in search of bargains. The relationship between Britain and France was one of self-confident appropriation and supersession: at Apsley House, the Waterloo Gallery remains an essay in Versailles-themed magnificence. In Thomas Lawrence’s coronation portrait of George IV, the king’s fingers rest on a bronze table made by Thomire, once owned by Britain’s great adversary, Bonaparte.

French history clearly gripped the imagination of British clients. Lord Stuart de Rothesay, ambassador in Paris after the Bourbon Restoration, was a noted buyer of porcelain-mounted furniture and panelling from dealer George Gunn, but also incorporated stones and stained glass from the manoir of Les Andeleys into his Highcliffe home. In the wake of the French Revolution, objects associated with the monarchy were rebranded in catalogues as antiques – a crucial moment in the modern definition of this term – even though at first they might have been made only recently; the ‘old Sèvres’ label was affixed to any soft-paste porcelain produced before the technique was discontinued in 1801. The Romantic cult of history was picturesque and associative, rather than archaeological. Lord Lonsdale was obsessed by Madame du Barry, and did not balk at having the dealer Edward Holmes Baldock paint her ‘DB’ ciphers on to undecorated pieces of Sèvres. Through such examples, Davis raises complex questions about pastiche, or what constituted a fake, in the early 19th century.

Vase (second half 18th century), Jingdezhen; mount (1808), Vulliamy & Sons. Royal Collection Trust/© HM Queen Elizabeth II 2020

As the careers of maker-dealers such as Monbro and Beurdeley demonstrate, the demarcations between retail and manufacture, or the original, the copy and the composite, were extremely fluid. If the first half of the book documents the political, commercial and cultural contexts of the ‘Anglo-Gallic’ moment, the second offers a meticulous analysis of specific artworks, noting the ingenuity of Robert Hume or the Vulliamy firm in adapting or refitting 18th-century objects for 19th-century palettes and domestic habits. Davis underlines the creativity of the British dealers’ response to the visual grammar of the old regime and their flair for customisation. The technical discussion of the objects’ material properties is combined with a sensitivity to their effects in the room: for instance, how gilt bronzes complemented the advent of gas lighting. The generous colour plates allow us to appreciate the subtlety of these hybrid objects, and how successfully they harmonised with the interiors at Bromley Hill, Belvoir Castle and Wrest Park.

Davis chronicles how the style took hold in Britain, radiating out from a circle of connoisseurs – such as George Watson Taylor and Ralph Bernal, both beneficiaries of plantation fortunes – to appear in pattern books and the pages of ‘silver fork’ novels (brilliantly mined here). Exhibitions at Gore House and at the Crystal Palace announced the arrival of this style in the cultural mainstream as the blue celeste of Sèvres was repackaged as Minton blue. The 1850s also marked the swansong of the ‘Anglo-Gallic’, overtaken by scholarship that began to classify and differentiate, as well as the reverence for provenance and the genuinely old. If Lionel de Rothschild’s opulent home in Piccadilly emerged out of the first phase of Anglo-French revival, it also heralded the next when, henceforth dubbed le goût Rothschild, it would cross the Atlantic and transform the homes of Gilded Age plutocrats. Tastemakers is a landmark book, beautifully written and executed, which challenges and redefines our ideas of both French and English taste.

The Tastemakers: British Dealers and the Anglo-Gallic Interior, 1785–1865 by Diana Davis is published by Getty Publications. The works illustrated in this review are currently on view in the exhibition ‘George IV: Art & Spectacle’ at The Queen’s Gallery, London (until 11 October).

From the July/August 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?