By the winter of 1939, Leonora Carrington found herself unable to accept the turn her life had taken in a few short months. Not long after the outbreak of the Second World War, her husband, the artist Max Ernst, had been arrested by the French authorities, who aligned his German citizenship with the threat of enemy invasion. Left to her own devices in the couple’s home in southern France, Carrington recorded her increasing sense of disorientation in a series of letters to her friend, the Argentine artist Leonor Fini. Beset by fear and depression, the world appeared to Carrington to have taken on new, unsettling dimensions: ‘a monstrous daily life’, she wrote to Fini, ‘intrudes on the life of the mind’. Despite the destructive nature of this intrusion, the contact the friends fostered through their correspondence sparked a creative approach to this moment’s monstrosities as well.

By the winter of 1939, Leonora Carrington found herself unable to accept the turn her life had taken in a few short months. Not long after the outbreak of the Second World War, her husband, the artist Max Ernst, had been arrested by the French authorities, who aligned his German citizenship with the threat of enemy invasion. Left to her own devices in the couple’s home in southern France, Carrington recorded her increasing sense of disorientation in a series of letters to her friend, the Argentine artist Leonor Fini. Beset by fear and depression, the world appeared to Carrington to have taken on new, unsettling dimensions: ‘a monstrous daily life’, she wrote to Fini, ‘intrudes on the life of the mind’. Despite the destructive nature of this intrusion, the contact the friends fostered through their correspondence sparked a creative approach to this moment’s monstrosities as well.

Carrington’s creative output during this period is unsettling to say the least. The stories she composed and shared with Fini, while stranded in a foreign country in a time of uncertainty and unrest, contain images in which feelings of cultural displacement merge with the horrors of loss and sacrifice. Gleaming, luxuriant descriptions of French haute cuisine and the grotesqueries of consumption serve as meditations on the violence, greed, and indulgence that Carrington struggles to digest – as well as a disquieting commentary on the frailty of her own weary body. The boundaries between reality and psyche begin to break down. A rose-coloured sweater that Fini sends Carrington to lift her spirits becomes, to Carrington’s mind, a ‘living animal’, which finds its way into her stories as a beautiful rose-coloured sheep that is made to suffer at the hands of a satanic figure.

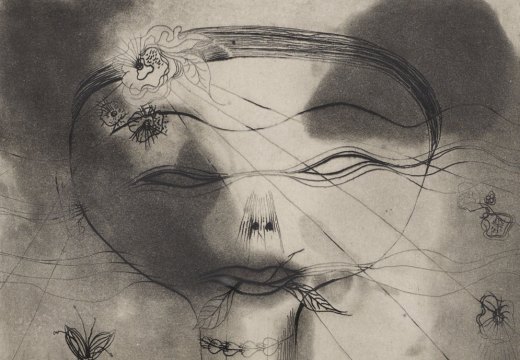

D’un jour à l’autre I (1938), Leonor Fini. Private collection. Courtesy Thames & Hudson

There is a fearful loneliness to these visions, yet they also contain a hidden source of strength. For the same ruins and remnants that preoccupy Carrington also appear in Fini’s paintings of the period, which Carrington may well have seen the year before catastrophe hit. The first image in Fini’s diptych D’un jour à l’autre (From One Day to Another, 1938) depicts a bathing pool in what looks like a classical temple, strewn with feathers and scraps of material. In the second image, these scraps appear to have metamorphosed into a group of ethereal women who bathe and speak together, one of whom resembles Carrington herself: standing tall, her leonine hair thrown back, this Leonora is a law unto herself, imbued with animalistic powers. From desolation, feminine camaraderie emerges and beguiles. Indeed, where Carrington might appear to draw on Fini’s works to find a language for her torment, she also seems to source the energy for transformation from her friend’s correspondence. As the war and Ernst’s incarceration wore on, Carrington found a means of survival in her creative female friendship: ‘NEVER NEVER will I become passive or docile,’ she told Fini in a rage of sudden resolution: ‘you are like me and I embrace you still more with admiration and affection.’

D’un jour à l’autre II (1938), Leonor Fini. Private collection. Courtesy Thames & Hudson

Such points of resistance and resilience are the focus of Whitney Chadwick’s Militant Muse, an ambitious foray into the lives and friendships of nine female artists who found themselves caught up, one way or another, in the early Surrealist movement. The dreamlike and disturbing images that emerge from Carrington and Fini’s shared experience may seem to epitomise the particular artistic project of Surrealism – especially its focus on the figural representation of unconscious fears and desires. For Chadwick, though, to trace the stories of Frida Kahlo and Lee Miller, Valentine Penrose and Claude Cahun, among others, is to trace an alternative history of Surrealist artistic production – a history in which experiments with selfhood and sexuality enabled these women to destroy the pedestals upon which the male Surrealists had placed them, and defy the constrictive power of the male gaze.

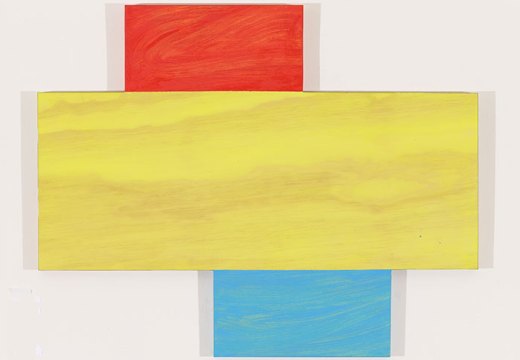

Ariane (c. 1934), Valentine Penrose. The Penrose Collection. Courtesy Thames & Hudson

As Chadwick reveals, this didn’t only mean producing artworks which explicitly undermined that gaze, although many of these women didn’t pull their punches when it came to subverting the misogyny of the Surrealist project. We need only think of Jacqueline Lamba’s Self-Portrait (1927) or Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait on the Bed (1938) to summon bold moments of self-definition that resist the fetishisation of a silent feminine ‘mystery’ to be found in works like Roland Penrose’s Winged Domino (1937). More important to Chadwick’s account is the recuperation of the roots of female Surrealist thought: the moments of trauma and the steadfast female relationships that nurtured new ways of negotiating the boundaries of sexuality, spirituality, and artistic expression, as well as the dimensions of a world at war.

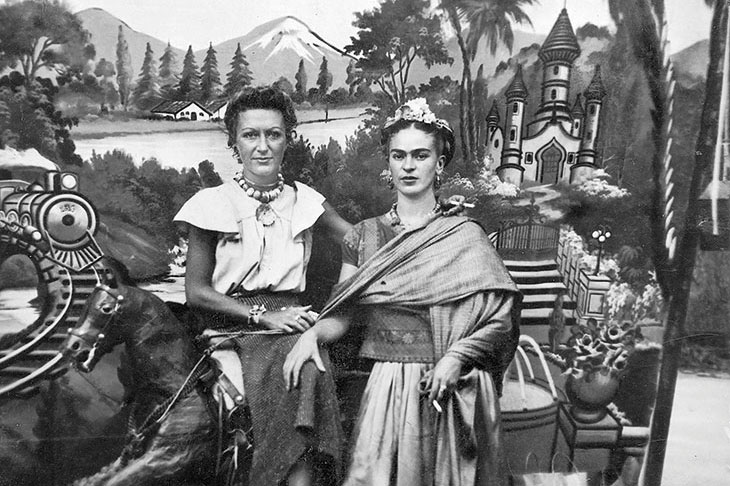

Here, the dissection of communism by André Breton, Diego Rivera, and Leon Trotsky in Mexico becomes background noise to the blossoming of friendship and artistic communion between Frida Kahlo and Jacqueline Lamba. Roland Penrose’s influence as an artist and collector is used to contextualise the achievements of his wives: Chadwick follows his first wife, Valentine Penrose, on her passage to India and the spiritual and sexual awakening it brings, and engages with the determination to represent global conflict that drove his second wife, Lee Miller, to the gates of Dachau at the end of the war. More than a straightforward group biography, Chadwick’s project is one of recontextualisation, which prompts us to view these women’s approach to their art not as a necessary offshoot of the Surrealist movement, but as an independent species of reaction to deeply felt moments of crisis and growth.

Jacqueline Lamba and Frida Kahlo in Pátzcuaro, Mexico, in 1938 (photographer unknown). Courtesy Thames & Hudson

At times, Chadwick’s dedication to allowing these women to speak for themselves results in moments of obliqueness, in which a reader uninitiated in decoding Surrealist imagery may find themselves lost in a forest of symbols and abstractions. That occasional need for guidance, though, illuminates what Chadwick manages to achieve so successfully elsewhere: namely, the sensitive handling of the private turmoils, national traumas, and strategies of survival that informed these women’s groundbreaking artistic experiments. As with any trauma, the magnitude of the disruption that engulfed these women was not always easy to confront, or acknowledge. Claude Cahun, for one, admitted the difficulty of grasping the reality of war, and understanding the connections between the Surrealist project and the upheaval of wartime life. Chadwick provides us with one way of re-establishing those connections and appreciating the remarkable lives of Surrealism’s neglected women.

The Militant Muse: Love, War and the Women of Surrealism by Whitney Chadwick is published by Thames & Hudson.

From the April issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?