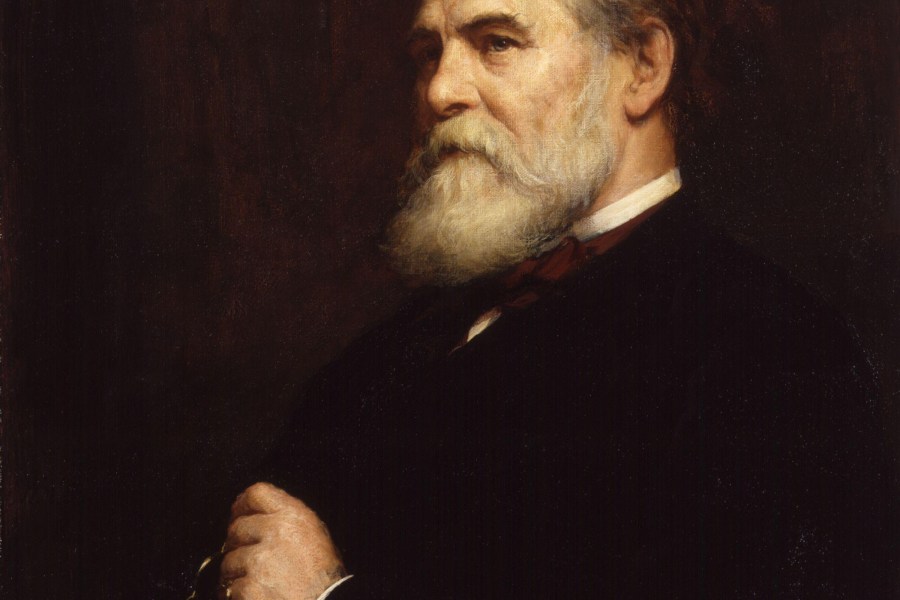

There are many architects to whom an old or beautiful building should not be entrusted. Work on such structures requires a certain reticence and modesty, characteristics not often found with very successful practitioners. In the 19th century, that dreadful amateur, Sir Edmund Beckett, aka Lord Grimthorpe, the despoiler of St Alban’s Abbey, is an obvious example. It is sad but necessary to place on this blacklist one of the greatest of Victorian Gothic Revivalists, John Loughborough Pearson (1817–97), whose bicentenary falls this year.

Pearson had several run-ins with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings after its foundation in 1877, owing to his arrogant disregard for antiquarian concerns. There was the case of the west front of Peterborough Cathedral, and the treatment of the side of Westminster Hall once the Law Courts by Soane were (alas) swept away in 1883. But the worst example is Pearson’s ‘restoration’ of the north transept of Westminster Abbey after he succeeded Gilbert Scott as Surveyor of the Fabric in 1879. The transept – the original main entrance to the royal church – had been repaired and partly recased in the early 18th century by Wren’s surveyor, Dickinson. At the end of his life, Scott had, on archaeological evidence, recreated the three great portals. Then Pearson was let loose on what was left. Ignoring evidence that Dickinson had merely renewed medieval stonework, he rebuilt (under a close hoarding) both rose window and gable tracery to his own design.

The north transept of Westminster Abbey, c. 1880, London, showing the portals by Gilbert Scott and the rose window prior to Pearson’s ‘restoration’

Old glass had to be cut up and altered to fit the new window. As for the gable tracery, for a later, more sensitive Surveyor, William Lethaby, this was ‘probably the most remarkable example of early tracery in England’. ‘The tragedy was that Pearson could not be trusted,’ the architect’s modern biographer, Anthony Quiney, admitted in his monograph of 1979. In the Abbey’s north transept, ‘not only did he ignore all the past but the thirteenth century, but he destroyed it as well. There lies his reputation.’

And that is a great pity, for when Pearson was designing new churches, he displayed genius. He is best known today as the architect of Truro Cathedral, the first new Anglican cathedral built since the Middle Ages (other than Wren’s rebuilding of St Paul’s). Pearson won a limited competition held in 1878 by the first bishop of the new diocese in Cornwall, Edward White Benson, and the building, with its triple spires, was largely complete by 1910. The site was confined, so the cathedral achieves dominance and dignity by rising high above the town, rather like Coutances in France. Normandy, indeed, was Pearson’s principal inspiration, though there are elements derived from Lincoln and Whitby. But it must be admitted that the result can seem disappointing. Like Scott, Street, or Bodley, when faced with designing a cathedral, Pearson seemed obliged to fall back on archaeological precedent. It was in smaller churches, less constrained by the site and by expectation, that these architects could display real originality in their chosen language.

Pearson was born in Brussels in 1817 but brought up in County Durham. His early buildings were Puginian, and not particularly remarkable. What changed him was reading Ruskin and, in consequence, making his first foreign study trip in 1853, to Germany and to France. The architecture of Normandy became the principal influence on his work, in particular such great buildings as the Abbaye aux Hommes (or of St-Étienne) at Caen as well as smaller rural churches like that at Bernières-sur-Mer with its magnificent steeple. The result was that Pearson became one of the principal exponents of what historians now call high Victorian gothic, with its emphasis on mass, geometry and unbroken wall planes, strongly influenced by Continental precedents. He became responsible for some of the toughest and most distinctive examples of this phase of the Revival, in his gaunt, urban brick church of St Peter in Vauxhall in London, and rural churches in Yorkshire like those at Appleton-le-Moors and South Dalton. Best of all, perhaps, is St Peter’s at Daylesford in Gloucestershire of 1857–63, an astonishing pyramidal composition of triangular gables, a central Normandy-style broach spire and rich, bold detail – but now sadly redundant, neglected, and difficult to see inside.

Ian Nairn once wrote that ‘If Pearson had died in 1867, when he was fifty, he would have been remembered not as a gentle Late Victorian architect, but as a violent Mid-Victorian one.’ But he didn’t: he lived on until Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and in those intervening years created some of the noblest, the most powerful and yet serene of all Victorian churches. In them – as he had done already – he exploited one particular aspect of French architecture to a degree of sophistication unequalled by any other architect – that is, vaulting. Pearson was a master of the masonry vault, adapting patterns of ribs to cover the most ingenious of internal spaces.

There was St John the Evangelist in Red Lion Square, London, which, wrote John Summerson, ‘displayed a mastery of the art of stone vaulting never seen since the Middle Ages’. Badly damaged in 1941, it still looked so magnificent that there were demands to preserve it as a memorial ruin – but in vain. But there survive large red brick basilicas by Pearson, vaulted throughout, in such places as Croydon, Upper Norwood, Maida Vale, Birmingham, Liverpool, Cullercoats near Newcastle, Bournemouth and Hove – not to mention Brisbane, Australia. Most still lack the tall, expensive towers and spires that Pearson planned for them. But the grandest of all these churches did receive the colossal version of the Bernières steeple that the architect intended: the Church of St Augustine in Kilburn, north-west London.

View towards the east end of St Augustine’s, Kilburn, London, designed by J.L. Pearson in 1870

It was designed in 1870 and almost a cathedral in scale and ambition; Nikolaus Pevsner thought it ‘one of the best churches of its date in the whole of England, a proud, honest, upright achievement’. It is the interior that impresses, a complex composition of confined and open spaces, with its double aisles, internal buttresses in the manner of Albi Cathedral, bridges across the transepts to carry a continuous gallery passage right around the building, and with lancet windows carried higher than the main vaults to give a further sense of complexity and grandeur. And every space, every passage, is vaulted in yellow brick. St Augustine’s, Kilburn, alone would justify Pearson’s reputation as one of the greats of the Victorian Gothic Revival.

Two Temple Place, London, designed by J.L. Pearson as the Astor Estate Office and constructed in the 1890s. Photo: Julian Nieman

Pearson also designed some surprising works which fall outside the Revival. William Waldorf Astor, the American millionaire politician and publisher, moved to England in 1891. Typically, he wanted an eminent architect to create suitably grand and lavish domestic interiors – and he lit on Pearson. These could not be gothic; instead, working with his son Frank, Pearson designed in a Tudor-cum-Elizabethan manner. One job was to revamp the interior of Charles Barry’s Cliveden; the other was to design the Astor Estate Office at Two Temple Place by the Thames. Here Pearson created a Tudor palace with rich panelled and decorated interiors – which now serve as a splendid setting for exhibitions organised by the Bulldog Trust. But this building is not the place to begin to explore Pearson’s greatness: ignore his crimes in Westminster, and take the Bakerloo Line to Kilburn.

From the November 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.