The exhibition of the work of Hercules Segers (1589/90–1633/40) held at the Rijksmuseum, and travelling to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is the greatest ever devoted to this extraordinary artist, who was without question one of the major talents in Amsterdam in the 1620s. Yet he is hardly a household name today, and many who are familiar with the world of art have never heard of him. There are two reasons for this. The first is that he was obscure in his own lifetime, and the surviving documentation on him is very poor; even his birth and death dates cannot be established. The second is the extreme rarity of his work: only 54 etchings by him are known, and his paintings are even rarer. The 18 shown in this exhibition constitute by far the largest gathering yet assembled; three are new to the literature, while two others have been elevated from the category of the doubtful to the firmly attributed. As this implies, the exhibition has been used as the opportunity to carry out much new research which will be published in a two-volume catalogue. The plate volume was ready in time for the Amsterdam showing, and never before have so many of his prints been reproduced in colour.

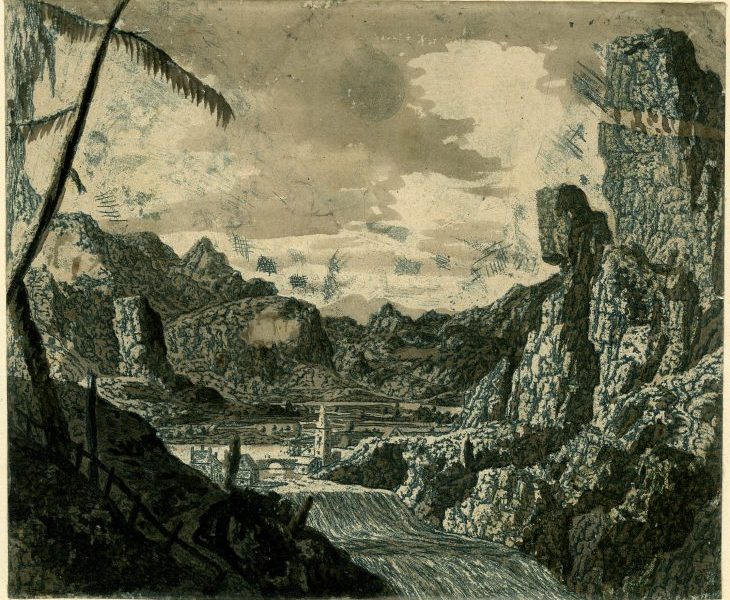

Landscape with a waterfall, second version, (c. 1625–27), Hercules Segers. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Rijksprentenkabinet has a unique distinction among the print rooms of the world. It holds the largest surviving group of prints of two of the great individualists of the Western tradition: the Master of the Housebook and Hercules Segers. From the 54 plates that Segers is known to have made, a paltry 183 impressions have survived (this is the number included in the old standard catalogue by Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann of 1973). Of those 183 impressions, 75 belong to Amsterdam, and some of these are unique. It is therefore impossible to mount any major Segers exhibition without support from the Rijksmuseum, and in this show their core group has been increased by loans from other institutions to show a total of 110 impressions. This is nearly two thirds of what survives, and it is difficult to see how a better or larger show could ever be put on. Not a single plate by Segers is dated, and even an approximate chronological development is impossible to agree on. So the approach adopted in the Rijksmuseum, which is the only feasible arrangement, was by subject. This worked well, and the prints were brilliantly lit to stand in dramatic contrast against a black surround.

Landscape with a waterfall, second version, (c. 1625–27), Hercules Segers. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

For many of the prints the organisers were able to line up a series of variant impressions from the same plate and this brought out just how great an oddity Segers is in the history of printmaking. The business of prints is based on the assumption that the requirement is to make a plate from which multiple impressions can be printed. To do this efficiently they need to be printed in a standardised way, and they needed to carry on them the text to explain what they were about and where more impressions could be purchased. Segers was not interested in any of this. His plates never carry any text, not even his name, and only rarely are two impressions printed in the same way. Rather they are almost invariably coloured, either by using coloured inks or by hand-colouring them after printing, and the effects are varied by printing on different surfaces: not simply ordinary printing paper, but linen, canvas, imported Japanese paper, and similar. Moreover Segers used a variety of weird ways of drawing on his plates and etching them, so that even impressions in plain black ink look nothing like the other sorts of print on the market in Amsterdam at the time. In short, it is almost misleading to call him a printmaker at all. Rather he used the base of a copper plate and a printing press to produce a varying unique object.

This rather obsessive and uncommercial approach to the copper plate must have severely limited his market. A later critic acutely described his work as printed paintings, but potential buyers at the time must have been bewildered by these objects that stood far apart from the prints that they were used to seeing, while yet being so small that they could hardly serve the function of a painting in decorating a wall. This presumably explains the extreme rarity of his work compared with an artist such as Rembrandt. Most prints at the time were published in runs of hundreds, if not thousands; even Rembrandt printed his plates in hundreds rather than tens. Segers’ works by comparison were one-offs, and so they hardly found their way into the albums of print collectors where they might have been preserved safely.

‘Hercules Segers’ opened at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (7 October 2016–8 January 2017), and is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from 13 February–21 May 2017.

From the March issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.