‘The Temperature of Sculpture’ is a paradox just about worthy of Jirō Takamatsu himself: a show somehow remarkable both for curiosity and incuriosity. On the one hand, Lisa Le Feuvre and the Henry Moore Institute have sought out and put a spotlight on the work of a figure who, despite his canonical status in Japan, is more or less completely unknown in Britain. This is Takamatsu’s first solo show at a public institution outside of Japan; for that alone, it is a worthy part of the institute’s mission to educate the British public in contemporary sculpture. But it is also a shame that the show’s curiosity seems to stop there: the natural questions that most viewers will have about Takamatsu, his influences, and the Japanese art world go frustratingly unanswered. Unless you happen to have a passable knowledge of post-war Japan and Japanese art (a lacuna most of us would admit to), the effect is to deprive viewers of a useful frame of reference for Takamatsu’s work.

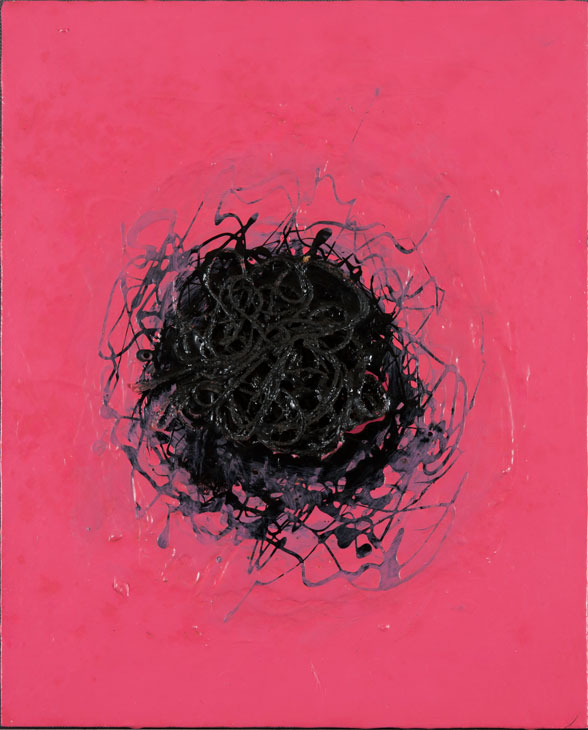

This complaint, of course, only presses in because, as the show makes clear, Takamatsu’s work is worth knowing about. His sculptural experiments in visibility, invisibility and divisibility delight in tickling the viewer’s preconceptions about depth, distance, and volume. The exhibition begins by examining works from the early 1960s, when Takamatsu moved from painting to sculpture, while at the same time delving into happening-style art ‘events’ with his collaborators in the ‘Hi-Red Center’ collective. At the centre of the first room are examples of the artist’s ‘Point’ series – experiments with something that, having no extension in either space or time, no volume or dimension, seems like the ultimate anti-sculptural concept. Takamatsu draws his points out into strings that go wandering the world on their own – from the dense wall-bound agglomerations of wire in Point (1961) and Point No. 15 (1961–62), to various knotted ropes originally designed to be pulled on and unbundled by curious viewers. In the famous Yamanote Line Incident (1962), Takamatsu and Hi-Red Center colleagues even unfurled one of his point-strings, knotted with domestic objects, around one of Tokyo’s main commuter routes as part of a larger occupation of public space.

Point No. 15 (1961–62), Jirō Takamatsu. © The Estate of Jirō Takamatsu. Courtesy Yumiko Chiba Associates / Stephen Friedman Gallery / Fergus McCaffrey

The preoccupation with the visibility of objects as they extend into space runs into the show’s second and third rooms, which present the artist’s experiments in shadow and perspective. A first glance at Shadow No. 241 (1968) shows only a white hook mounted on a white board. Look closer, and, alongside the hook’s shadow, cast by the gallery lights, are two further painted shadows, both showing the key that should be, but is not, hanging from the hook. The same technique is employed in Shadows on the Door (1968), where the shadows of a man and woman are seen, opening a set of double doors for the viewer. It is not quite trompe-l’oeil since the eye is not tricked in any real sense; it is something deeper and more affecting.

The couple in Shadows on the Door are a tender and domestic absence and presence, evoking both the sense that one is intruding on a private moment, and that the moment has been and gone. It is a playful piece (originally viewers were invited to open and close the doors themselves, casting their own shadows), and a romantic one (I found myself constructing a narrative about the relationship between the invisible participants in Takamatsu’s shadow play). But is also, in the Japanese context, sad. A central doctrine of Japanese aesthetics, wabi-sabi, focuses on the three defining aspects all human existence: mujō, ku, and kū; impermanence, suffering, and emptiness or absence. Here are two impermanent bodies casting permanent shadows; and/or two empty bodies, whose shadows would have us believe they are not empty.

Temporary Enclosure of Carioca Building Construction Site (1971), Jirō Takamatsu. © The Estate of Jirō Takamatsu. Courtesy Yumiko Chiba Associates / Stephen Friedman Gallery / Fergus McCaffrey

Looking at Shadows on the Door was also the first point in the exhibition where I began to become frustrated with the show’s lack of context – and with the way that lack hobbles deeper thought about the works. With the emphasis on Takamatsu as a kind of sculptural researcher, ‘The Temperature of Sculpture’ maps a largely apolitical narrative. Here, Shadows on the Door sits alongside other experiments in visual distortion as if it is to be taken as part of a sculptural funhouse – other exhibits include a table and chairs impossibly diminishing into non-perspectival space.

The implication, encouraged by Lisa Le Feuvre’s catalogue essay, is that we should see Takamatsu as an enjoyable navel-gazer, preoccupied with playfully testing out ‘alternative ways of seeing, feeling and calibrating our temperature in the world’. But, standing in front of Takamatsu’s shadow-couple, with wabi-sabi in mind, it is hard not to remember that Japan is the only place on earth to have real shadows that work in this same way, persisting long after the bodies that cast them have disappeared: in Hiroshima. Even a little information about Shōwa-era Japan would reveal, I think, a different artist behind the portrait presented by ‘The Temperature of Sculpture’.

The String in the Bottle No. 1125 (1963/1985), Jirō Takamatsu. © The Estate of Jirō Takamatsu. Courtesy Yumiko Chiba Associates / Stephen Friedman Gallery / Fergus McCaffrey

After all, ‘post-war’ is a crucial adjective here. Shōwa – the period of Hirohito’s rule, from 1926–89 – was a time of astonishing change and turbulence for Japan. Born in 1936, Takamatsu could hardly escape the conundrums of political and aesthetic identity facing a nation negotiating its relationship to American military, political and cultural power under the persistent shadow of two mushroom clouds. During the 1960s – the period covered by ‘The Temperature of Sculpture – there were recurrent protests, around both the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty set for 1970, with militant communists even forming their own Red Army Faction (which declared war on the Japanese state in 1969, and later became the Japanese Red Army). Even the youth embrace of American pop-culture was overhung by a sense of imperialism: a film of the 1965 tour by The Ventures, the biggest American stars in Japan, was titled Beloved Invaders.

In this context, Takamatsu’s work with Hi-Red Center – only fragments of which appear here – was militantly political in a way that casts a very different light on even the most playful works in ‘The Temperature of Sculpture’. Hi-Red Center engaged in acts that directly grappled with the nation’s past and future, from physically scrubbing streets that, in the run up to the Olympics had already been cleansed of beggars and ‘thought perverts’, down to measuring up volunteers for individually tailored nuclear shelters, the size and shape of a single body. Playful, but nakedly political. And if the works in ‘The Temperature of Sculpture’ emphasise the playful, this does not, I suspect, mean that the political is absent – even if it has been absented in the curation.

‘Jirō Takamatsu: The Temperature of Sculpture’ is at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, until 22 October 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?