In November 2011, Andreas Gursky’s Rhein II sold for $4.3m at Christie’s in New York, and set a world record price for a photograph at auction that stands today. Measuring nearly 4m across, this austere, almost abstract photograph of the Rhine River is composed of bands of grey and green, with every fleck of human distraction – cyclists, walkers, a factory building – digitally removed. The record had been set in 2007 by another Gursky work – his dizzying, brightly coloured and digitally manipulated 99 Cent II Diptychon (2001), when it sold for £1.7m at Sotheby’s London. Today, seven of the 20 most expensive photographic works at auction are by Gursky. Laura Paterson, head of photographs at Bonhams in New York, remarks: ‘Gursky’s world record price in 2011 changed forever how these photographs were regarded in terms of both contemporary art and their value.’ If the 2011 sale asserted Gursky’s market pre-eminence, it also represented the secondary-market apotheosis of the highly objective, rigorously composed, conceptually driven photography associated with the Düsseldorf School.

Gursky, born in Leipzig in 1955, was part of a generation of students, including Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, and Elger Esser, to study photography at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf under the renowned Bernd Becher (1931–2007) and his wife, Hilla (1934–2015). Since 1959, the Bechers had, through their compulsive documentation of soon-to-be obsolete industrial structures – barns, water towers, grain elevators, coal bunkers, gas tanks, steel plants, oil refineries, blast furnaces, storage silos – pioneered a style of photography that was to have a lasting impact not just on their students, but on minimalist and conceptual art in general. Spare, heroic, devoid of people, without distractions of sun or shadow, the Bechers’ black and white prints were compellingly displayed in grids or ‘typologies’, or printed in large formats. What began as documentation became a five-decade-long meditation on history, beauty, function and obsolescence.

The Bechers’ significance in terms of contemporary art has been acknowledged in Europe and North America through museum exhibitions since the 1970s. In 1990, they were awarded a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Represented by Sprüth Magers, since their deaths the market in their now definitive pool of works has intensified. While individual prints, both offset and silver gelatin, can sell at auction for under $5,000, highly sought-after groupings, especially from the 1960s and 1970s, change hands for much more. As Genevieve Janvrin, Phillips’ head of photographs in Europe, points out, each ‘typology’ is distinct, even if the single images can be repeated, making them in effect unique works. The record auction price for the Bechers is the €411,000 for Wassertürme (Trichter), achieved at Sotheby’s Paris in November 2015, just a month after Hilla’s death. This grid of nine silver prints, composed in 1972 with an installation sketch on the reverse, was first exhibited at Documenta 5 that same year. At Phillips in London on 8 March, an arrangement of 15 water towers went for £293,000. For Janvrin, this recent sale confirms the strength of the Bechers’ market, which, she adds, ‘has a ripple effect on the next generation, because the group is so clearly connected’.

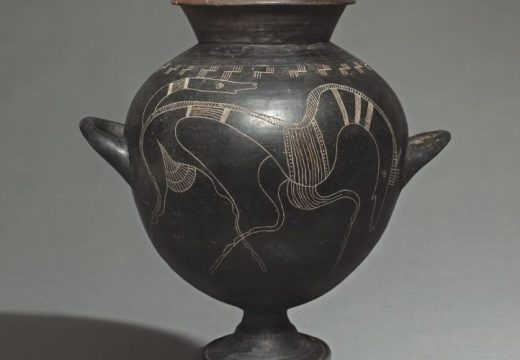

Jpeg pt01 (2006), Thomas Ruff. © 2017 Christie’s Images Limited

Last November Janvrin sold a work from Thomas Struth’s sought-after Museum Photographs series, produced between 1989 and 1990. Art Institute of Chicago II, Chicago, 1990, one of an edition of 10, achieved £635,000. Alongside Gursky and Thomas Ruff, Struth is a pioneer in the creation of bold, emotionally detached, large-format colour images, although he is also known for his smaller-scale street scenes. His Pantheon, Rome (1990) sold at Sotheby’s New York for $1.8m in 2015, establishing his world record price. Another edition of this photograph sold two years earlier at Sotheby’s London for £818,500. Struth is represented by Marian Goodman Gallery and Galerie Max Hetzler, among others, while Ruff shows with equally prestigious galleries such as David Zwirner and Gagosian; both are well represented in museum collections internationally. The highest price for Thomas Ruff’s work was reached in early March this year at Christie’s London. His Jpeg pt01 (2006), with a pre-sale estimate of £20,000–£30,000, sold for £197,000. Ruff’s diverse output includes stark monumental portraits, his Häuser (austere architectural facades), Sterne (night skies), and a 2003 series of pixellated nudes. Candida Höfer’s awe-inspiring unpeopled interiors have also been steadily rising in value at auction. Her artist record is for Biblioteca Geral da Universidade de Coimbra IV of 2006, which fetched £80,500 at Christie’s London in 2015.

These are the artists of this school most sought after by collectors, according to Janvrin. ‘Their market is global and it cross-pollinates between photography collectors and contemporary art collectors,’ she says. The Bechers’ students are linked, Cologne-based dealer Thomas Zander suggests, less by subject matter than by the conceptual ambition and technical skill the Bechers instilled in them. ‘The artists of the Düsseldorf School know what photography is – both in the technical and the aesthetic sense,’ he says. ‘Furthermore, their photography is seen in the context of contemporary art, since all artists of the Düsseldorf School above all follow a conceptual approach.’ He will be showing works by Höfer at Photo London (18–21 May). ‘Candida Höfer’s classic subjects, the libraries, for instance, are certainly always in demand,’ says Zander. ‘However, there are new works, such as the dye transfer prints or her photographs of the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, which are equally coveted.’

La Grande Be, Frankreich (2009), Elger Esser. Thaddaeus Ropac, €42,000

Thaddaeus Ropac observes about the younger, more literary and romantic Elger Esser, sometimes referred to as a ‘heretic’ of the Düsseldorf School, whom he represents, that the conceptualism of Esser’s projects and the multiple resonances of his prints are sometimes missed, so seduced are collectors by his chemically washed-out landscapes. He reports that Esser’s first New York gallerist, the influential Ileana Sonnabend, would say: ‘The Americans would just look at the image.’ Ropac sells Esser’s work mostly to Europeans, with strong interest from institutions, and currently has prints available from around €27,000–€42,000.

Brandei Estes, head of photographs at Sotheby’s London, remarks that the success of the school’s large-format prints, especially Gursky’s epic images, has also revived interest in the earlier works of figures such as Struth, whose black and white Crosby Street (1978) sold at Sotheby’s New York last October for $61,250. She warns that condition is of huge importance. Images printed before 2005 can have colour fading, while the distinctive Diasec method of face-mounting the prints with acrylic can leave prints vulnerable to damage. ‘Condition is key for this market,’ says Janvrin. ‘The vision of the whole school is precision, so the images need to be pristine, clean and clear.’

From the May 2017 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home