A few years after its foundation in 1886, a critic referred to the New English Art Club as that ‘Steery, Starry, Stotty lot of painters’. The reference was to Wilson Steer, Sydney Star and the two Stotts – William Stott of Oldham and (William) Edward Stott (1855–1918), who came from nearby Rochdale but was no relation. Apart from youth and membership of the NEAC, what these four men had in common was a love of French plein air painting in general and the work of Jules Bastien-Lepage in particular.

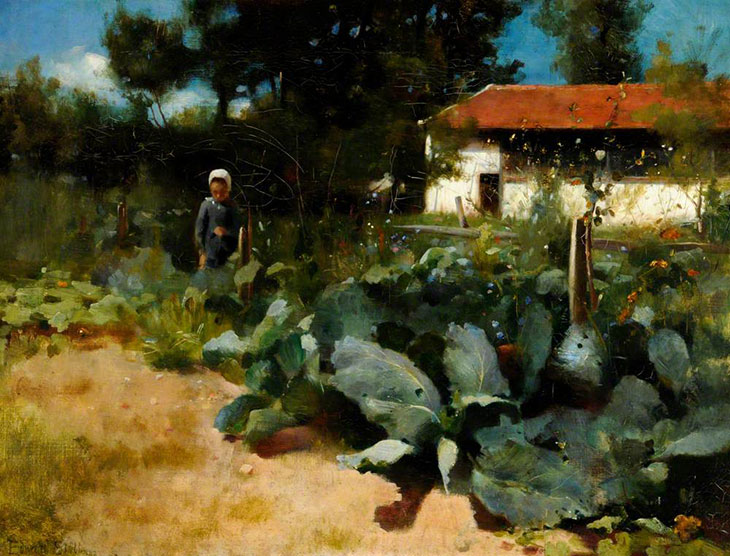

Edward Stott was the son of a Lancashire mill owner, whose father forced him to work in the family business. But in 1883, with financial help from an unknown benefactor, he escaped the paternal influence and went to Paris, where he enrolled in the atelier of Carolus-Duran, later transferring to the École des Beaux Arts. One of the earliest paintings in the Towner Art Gallery’s current exhibition is the lustrous A French Kitchen Garden (1883), which shows how quickly Stott mastered the techniques and tricks of plein air painting, such as the exploitation of dull grey days undisturbed by transient effects of sunlight and shadow. For a few brief years in the 1880s cabbage patches such as this one, with their big vegetable forms, were a popular motif with young British painters such as Stott, George Clausen, James Guthrie, and William York Macgregor. They had their favourite painting grounds in the French countryside, particularly Grez-sur-Loing near Fontainebleau.

A French Kitchen Garden (1883), Edward Stott. Museums Sheffield

Returning to England, Stott sought similar rural sites for his paintings. He and the Irish artist Walter Osborne went first to Evesham in Worcestershire, and then to the Hampshire village of Wherwell, before Stott alighted in 1885 upon Amberley in West Sussex. For the rest of his life Amberley was to provide him with the settings and themes for his paintings. Over the next three decades he also played a significant role in preserving the village as the pastoral idyll it remains today, buying up its old thatched cottages and preserving them for posterity. It is this association with Sussex and the South Downs that makes Eastbourne rather than Rochdale the ideal place for this important retrospective marking the centenary of Stott’s death.

Approaching Night (c. 1917), Edward Stott. Touchstones Rochdale. Photo: © Rochdale Arts & Heritage Service

Amberley was for Stott what Damvillers was to Bastien-Lepage, and the South Downs were as important and universal to him as Inkpen Beacon and Wessex were to Thomas Hardy. For him the surrounding landscape was imbued with the charm of paradise combined with the weight and mystery of aeons of history. Towards the end of his life, it seemed quite natural that the Good Samaritan, his charge precariously balanced on a donkey, should pass quietly in front of these chalk hills (The Good Samaritan [1910]), and that Christ should be entombed in this familiar setting (The Entombment [1915]). These overtly religious themes filtered their way into paintings such as Approaching Night (1917), which hovers in the penumbra between everyday life and holy vision. Even in his most naturalistic scenes there is the hint of something divine in the mundane yet timeless acts of tending sheep, harvesting or hanging out the washing.

Just as Stott’s subject matter was finely nuanced his technique, too, gradually changed from the bold handling of his French period to an increasingly refined application of multiple layers of thinly applied paint resulting in the subdued glow of enamel. His method was painstaking and time-consuming, resulting in a modest oeuvre in oils, backed up by a large body of pastel studies. His propensity for low light led him to eschew the seductive sun-drenched Impressionism, in favour of early morning, evening or moonlit scenes: the magic of dappled dawn-lit foliage, as in The Old Gate (1895), or the effect of the setting sun filtered through sheets in Washing Day (1899), which positively throb with warmth and colour. One needs to stand in front of Lambing Time (1906) for some moments before perceiving the shadowy form of the shepherd seated on the steps of his van, keeping an eye and an ear on his flock through the darkest hours of the night. This beautiful work could serve as an illustration for one of Hardy’s Wessex novels.

Washing Day (1899), Edward Stott. Watts Gallery Trust

With a first-hand experience of the South Downs available just beyond the gallery, the exhibition, which combines a whiff of nostalgia with a delight in the textural and luminous effects of paint, is well worth a day trip to see. It is accompanied by a generously illustrated book by Valerie Webb: a valuable addition to the growing body of works devoted to exploring the strand of British realist painting that flourished between Pre-Raphaelitism and the First World War.

‘Edward Stott: A Master of Colour and Atmosphere’ is at the Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, until 16 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?