This review first appeared in the January issue of Apollo

In 1568 Giorgio Vasari added a section to the technical introduction of his Lives that explained the use of drawing in painting, sculpture and architecture, known as the arts of disegno. Vasari states that some sculptors do not have much practice in drawing and, accordingly, do not draw on paper, but instead practise the art of disegno through modelling in wax and clay. An exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum explores this claim and the relationship between drawing and sculpture on the Italian peninsula in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Systematic research of specific sculptors’ drawings has made much progress, but, as a group, the drawings by Italian Renaissance sculptors have received little critical attention. During the 1940s, Erwin Gradmann and Harald Keller each attempted to define a category of drawings unique to sculptors. Although they represent the first such attempts by modern scholars, these studies were far from exhaustive and were weakened by the breadth of their temporal and geographic scope. A similarly broad approach informed the 1981 exhibition curated by Colin Eisler at New York’s Drawing Center, which included drawings by sculptors spanning more than 500 years. Authorities such as Charles Avery and Catherine Monbeig Goguel have written more focused, if brief, essays that surveyed the graphic practices of Italian Renaissance sculptors. Going beyond these previous investigations, the present exhibition, curated by Michael Cole and Oliver Tostmann, offers unprecedented insight into the function, context and evolution of drawings by the 15th- and 16th-century Italian sculptors.

The exhibited drawings are shown in two rooms and are organised according to their artistic function, with the exception of a small monographic grouping dedicated to Baccio Bandinelli (1493–1560). The smaller of the two rooms is devoted to the general theme of study, specifically the practice of creating drawings after three-dimensional works such as small-scale models and antique statues. The viewer is here reminded that, just as preparatory drawings could inform finished sculptures, so study drawings made after works in the round influenced the graphic practices of Renaissance artists when they visualised three dimensions on paper. The larger room is devoted in part to the work of Bandinelli as well as drawings by sculptors for reliefs of the human figure and for architecture.

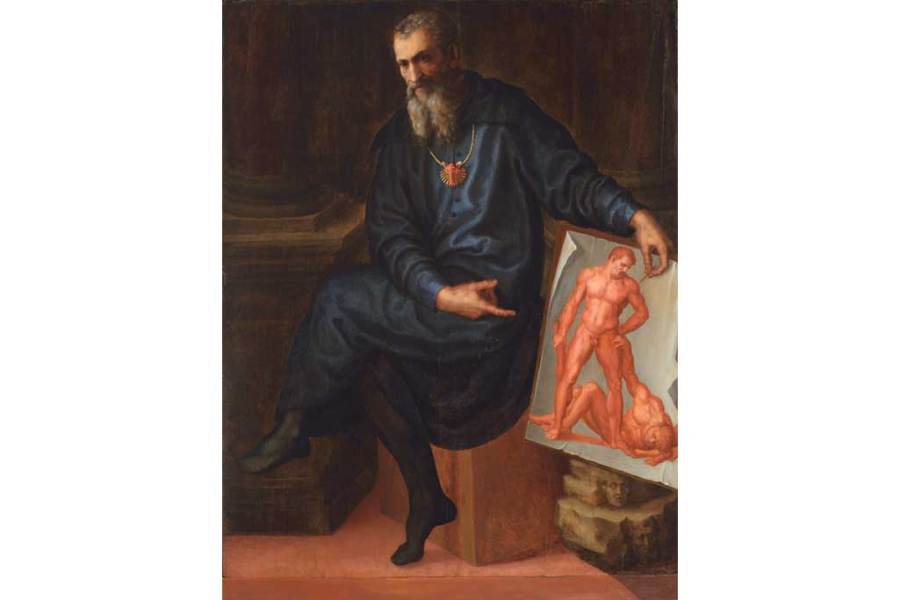

In many ways the exhibition and catalogue centre on Bandinelli, whose name would undoubtedly have been included in the title were he more popular. Along with the exhibition at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence in 2014, the present show directs further attention to this important sculptor, draughtsman, print designer and, occasionally, painter. On view are a handful of drawings, three of which are preparatory to the artist’s best-known work: the Hercules and Cacus (1525–34) installed outside the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. These studies are a rare opportunity to observe the graphic evolution of a large scale 16th-century work in the round. They are also particularly appropriate given the prominent display – in the gallery as well as on the cover of the exhibition catalogue – of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s self-portrait of Bandinelli (c. 1545), in which he presents himself as a draughtsman by conspicuously pointing to a drawing of the group that offers an alternative arrangement of the figures.

To characterise most Renaissance artists as practitioners of a single discipline such as sculpture would be misguided and the organisers of the exhibition rightly seek to present the multidisciplinary nature of the artists in question. The exhibition catalogue and wall text emphasise the importance of drawing to goldsmiths, in whose workshops several major sculptors were trained, and the necessity of drawing for sculptors who had ambitions to design architecture. The curators should also be commended for the manner in which they have approached issues of authenticity. The survival rate of Renaissance sculptors’ drawings is relatively low compared to that of contemporary painters. Thus, our understanding of several sculptors as draughtsmen remains unclear, and difficult questions of attribution abound. The contributors to the exhibition and catalogue remain flexible in this regard as they unfold the complex attributional factors in the case of, for example, the sheet from Vasari’s Libro de’ Disegni, whose status as the single surviving drawing by Donatello has often been disputed.

Several of the drawings take on additional interest as a result of their pairing with related three-dimensional works. The viewer has the opportunity to compare, side by side, a preparatory pen-and-ink drawing from the Louvre by Benvenuto Cellini (1500–71) and the bronze relief with which it is connected (the panel depicting Perseus saving Andromeda from death, originally installed at the base of the artist’s well known statue of Perseus with the Head of Medusa [1545–53]). The bronze, which features passages in such low relief that they appear to be drawn rather than sculpted, is on loan from the Bargello and makes its first appearance outside Italy. Also on display is Cellini’s bronze Satyr (1543–45), which was created for the main entrance of François I’s Château of Fontainebleau; the elaborate mixed-media drawing he made to record his work, is unlike anything surviving by contemporary sculptors, or indeed draughtsmen of any kind. A similar juxtaposition is made of Michelangelo’s studies in two and three dimensions. His terracotta bozzetto of a twisted female figure is shown with four reunited drawings, made contemporaneously (and dispersed in the 19th century), recording an antique Venus from multiple viewpoints.

‘Donatello, Michelangelo, Cellini: Sculptors’ Drawings from Renaissance Italy’ assembles representative examples by a group of important Renaissance sculptors. Furthermore, the catalogue is a valuable introduction to the reasons why Renaissance sculptors made drawings and the ways in which these studies related to their works. Ultimately, the exhibition brings together the often anachronistically separated practices of drawing and sculpting. In so doing, it furthers our understanding of some of the greatest sculptors of the early modern period.

‘Donatello, Michelangelo, Cellini: Sculptors’ Drawings from Renaissance Italy’ is at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, until 19 January 2015.

Catalogue by Michael Cole, Oliver Tostmann et al.

ISBN 9781907372704 (paperback), £35 (Paul Holberton Publishing)

Click here to buy the current issue of Apollo

Related Articles

First Look: ‘Sculptors’ Drawings’ at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (Michael Cole)

Gallery: ‘Sculptors’ Drawings’ at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?