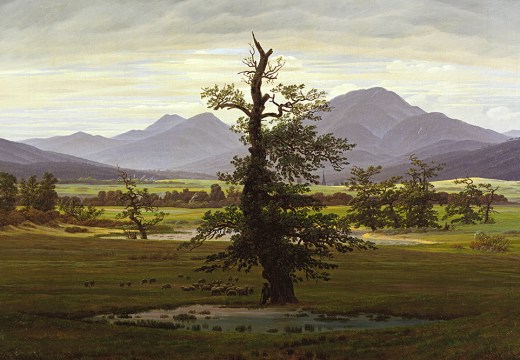

The current display of Old Masters at Christie’s (until 6 December) gives pride of place to Anthony van Dyck’s painting of Charles I’s daughter, Princess Mary. Painted in 1637, to mark her marriage to William of Orange, it is an exceptional example of the artist’s renowned late work at the court of Charles I. But not to be overlooked is a second Van Dyck from the collection of the late Dutch businessman Eric Albada Jelgersma. The Double portrait of George Villiers, Marquess and later 1st Duke of Buckingham and his wife Katherine Manners, as Venus and Adonis is a significant early work by the artist that has rarely been exhibited in public.

Portrait of Princess Mary (1631–1660), daughter of King Charles I of England, full-length, in a pink dress decorated with silver embroidery and ribbons (1641), Anthony van Dyck. Estimate £5m–£8m. Courtesy Christie’s

This painting gives perhaps the clearest example of the influence of Peter Paul Rubens on the young Van Dyck – indeed, the piece was misattributed to Rubens well into the 20th century, assumed to be a late self-portrait of the artist with his wife, Helena Fourment, whom he married in 1630 (the painting is now dated to 1620–21). Van Dyck had worked in Rubens’ studio in Antwerp until 1620, and the great master described him as ‘the best of my pupils’. It wasn’t long before he was on the radar of George Villiers – the great art collector and royal favourite of both James I and Charles I – who invited the painter to the court in London. The painting was commissioned when Van Dyck was just 21, during this visit, most likely to celebrate Villiers’ marriage to Katherine Manners, in May of that year. Noted as a beauty, Manners was the richest woman in Britain outside of the royal family: for Villiers, the youngest son from the second marriage of a minor gentleman, to marry such a woman was an extraordinary coup.

If the match seems somewhat unusual, the portrait is positively outlandish. It blends two genres – the marital portrait and a classical scene – in a manner never seen in English or Flemish portraiture before. The choice of classical figures for the newlyweds to enact, Venus and Adonis, is remarkable in itself, yet the real audacity is in the presentation of the couple. Villiers and his wife are depicted in a state of undress: the flowing blue cloth of Villiers/Adonis barely covers his body, and the contours of the material draw the viewer’s eye unerringly towards his crotch; while Katherine/Venus’s hand appears to be all that prevents her sumptuous orange cloth from revealing more than her breasts. While there is nothing strange for Venus to be at least partially nude, and such nakedness might have been commonplace in court masques of the time (even Charles I’s queen, Henrietta Maria of France, had appeared in a masque with breasts exposed), it was unheard of for a lady at court to be portrayed in this way. It reinforces the image of Villiers as a radical and ostentatious – even transgressive – courtier.

In the Metamophoses, Ovid tells of how Venus, accidentally pierced by Cupid’s arrow, falls desperately in love with the beautiful Adonis. Adonis is a great hunter and, despite Venus’s pleadings with him to stay with her, he goes out to hunt and is killed by a boar. It is easy to see why the narrative might have appealed to Villiers: a handsome, athletic youth is adored by the goddess of love, who is here transposed into Katherine Manners, one of the most sought-after matches in England. Yet Ovid’s Adonis, while not immune to Venus’s charms, is desperate to return to the hunt (and thus hastens his own death). By contrast, Adonis/Villiers is doting on his love, staring adoringly at her with his arm wrapped around her shoulder. In Van Dyck’s painting only the hunting dog seems impatient to return to the field.

Double portrait of George Villiers, Marquess and later 1st Duke of Buckingham (1592–1628) and his wife, Katherine Manners (1603–1649), as Venus and Adonis (1620–21), Anthony van Dyck. Estimate £2.5m–£3.5m. Courtesy Christie’s

The dog’s posture links this painting back to Van Dyck’s other treatment of this story (now in a private collection in Madrid), in which he recounts the more conventional narrative. Drawing on earlier depictions by Titian and Rubens, Van Dyck shows Venus clinging to Adonis, begging him not to go. But while there are marked parallels in composition between the two works – the placement of a tree to the right of Venus, the ‘attire’ of the figures, and the identical (and distinctly baroque) dogs – the two figures of the later work are a radical reinterpretation of the story. Venus’s desperate gaze is replaced by Manners’ poised certitude, and Adonis’s impatience becomes Villiers’ lingering embrace.

Like the mythical youth, Villiers was also struck down in his prime – killed not by the wild boar he hunted, but by one of the many enemies he had accrued as the flamboyant favourite of two kings. His influence on English painting, however, is undeniable: Van Dyck returned to become court painter in 1630 and under Villiers’ tutelage, Charles I assembled one of the great art collections, part of which was reconstructed for public view in the Royal Academy’s exhibition earlier this year.

The Old Masters evening sale and the Eric Albada Jelgersma Collection evening sale are both at Christie’s, London on 6 December.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?