‘Everything seems to suggest that there is little connection between an object and what represents it,’ wrote René Magritte in December 1929 in ‘Words and Images’, a set of illustrated statements published in the final issue of André Breton’s journal La Révolution surréaliste. His years in Paris (1927–30) were drawing to a close, and the text was a summary of his findings from that busy and experimental period of word and picture play.

After encountering the Surrealists, Magritte sought new means of representation by merging and muddling his pristine figuration with globular abstractions and deliberately misleading labels, frequently treating the canvas like a collage that was free from any inherent logic. It was out of this exploration that Magritte produced his best known painting, La Trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) in 1929. At the time, however, he was failing to get real recognition for his work and his return to Brussels had a dejected air about it. It is on these pivotal years that ‘René Magritte (Or: The Rule of Metaphor)’ at Luxembourg & Dayan focuses, paying particular attention to the artist’s use of metaphor.

Le genre nocturne (1928), René Magritte. Private collection. Photo: Damien Griffiths; © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

If the show has a fault, it is the fairly unassuming start that surprises the visitor, so that you have seen half the exhibition before stepping a few feet through the door, yet can find no indications of what you are looking at or where it will lead. This does, however, begin to feel uncannily premeditated once you notice the impeccable attention to detail throughout the display, from the orange-tinted burgundy walls, which could have come straight from Magritte’s own palette, to his distinctive font and spacing on each exhibition leaflet. Best of all is an unspoken nod to the ‘Word Vs Image’ exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York, visible here in the unusual hang, which places one canvas at a head-tilting height next to every work hung at eye level and is charged with Surrealist suggestion.

To reflect the oscillations in Magritte’s style in this period, the exhibition rejects chronology in favour of presenting the works in pairs, which have been chosen to show the balance between the artist’s use of figuration and abstraction. In a further Magrittean twist, just beneath the stylish surface lies a remarkable conceptual depth. Yuval Etgar’s catalogue essay analyses Magritte’s use of the metaphor through the lens of Nietzsche, a Surrealist favourite, reprinting in full the philosopher’s essay ‘On Truth and Lying in a Nonmoral Sense’.

Installation view of ‘René Magritte (Or: The Rule of Metaphor)’ at Luxembourg & Dayan.

Photo: Damien Griffiths; courtesy Luxembourg & Dayan; © © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

If metaphors generally exist within the same system of signs, allowing, for instance, words to be substituted by other words, Magritte believed that ‘in a picture, words are of the same substance as images’. And so, in his paintings at least, images and words could be interchanged freely. Because Magritte’s metaphors displace words or images into unusual contexts and imbue them with new meanings, they revive language and open up its codes to infinite interpretation – as Etgar notes, ‘a good metaphor cannot be deciphered, only unpacked’.

In practice, as the exhibition at Luxembourg & Dayan emphasises, Magritte’s word-picture metaphors require the viewer’s participation. In the tiny drawing called L’usage de la parole (c. 1929), a collection of shadowed slabs bear tags that roughly correspond to their position floating on a sketchy sea – ‘horizon’ drifts into the distance, while ‘nuage’ is suspended in the sky. The image is at once stripped of meaning – as Magritte quipped, ‘sometimes a word merely serves to designate itself’ – and yet invites our interpretation, returning us to what Nietzsche terms the ‘artistically creative subject’.

La clef des songes (1927), René Magritte. Courtesy Bpk/Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen; © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2018

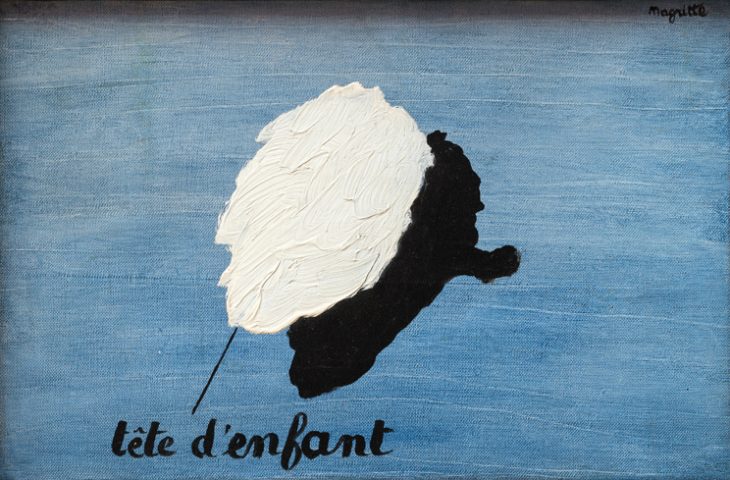

With Le parfum de l’abîme (1928), Magritte addresses our compulsion to comprehend the forms that surround us through labels and categorisation. The image mimics cloud-watching, with a thickly impastoed white blob over pale blue that has been designated ‘tête d’enfant’ in a black scrawl. Its shadow spouts a tiny trunk, just reminiscent of an elephant, and for a moment you feel you might have misread. But no, the label simply sounds enough like ‘elephant’ to trip you up and ridicule the arbitrary nature of words as representations.

The exhibition ends with a solitary line of text: ‘An object is not so wedded to its name that one cannot find another which suits it better.’ Magritte is urging us to question what we think we know and imagine new modes of expression and representation. He dares to envisage a language that is less coherent, but also less inhibited. This is not just a game to Magritte, but testament to his belief that ‘art evokes the mystery without which the world would not exist’.

‘René Magritte (Or: The Rule of Metaphor): Paintings from the Years 1927–30’ is at Luxembourg & Dayan, London, until 12 May.