Since the founding of Asian Art in London (AAL) in 1998, the Asian art market has transformed almost beyond recognition (and is poised to change again with the introduction of a 15 per cent tax on all Chinese imports of art and antiques into the US, not to mention uncertainties over Hong Kong). While AAL, along with the London art trade itself, has adapted to reflect these changes, the reasons for its success remain the same. London, still the most international of all Asian art markets, offers enthusiasts outstanding museum collections to visit and unrivalled, wide-ranging scholarly expertise from its art dealers and auctioneers as well as in its academic institutions. ‘It is a fantastic centre of Asian art,’ enthuses AAL chairman Leila de Vos van Steenwijk, ‘and a great moment to convene here. A huge number of people make the effort to come over.’

As with all art ‘weeks’, AAL depends on critical mass. This year’s event (31 October–9 November) sees 46 participants – 33 dealers and 13 auction houses – offering works of art of all media and ranging from the Middle East to India and Nepal, South East Asia, China and Japan, and from antiquities to contemporary work. As always, the late-night gallery openings in Kensington Church Street (2 November), St James’s (3 November) and Mayfair (4 November) lend a convivial party atmosphere to the gallery crawl. More recent additions are the regional and overseas auction-houses that join Bonham’s, Christie’s and Sotheby’s to preview upcoming Asian art sales in central London: Duke’s of Dorchester, Lempertz (Cologne), Lyon & Turnbull (Edinburgh), Nagel Auktionen (Stuttgart), One Larasati Arts (Singapore), Roseberys (West Norwood), Sworders (Stansted Mountfitchet) and Woolley & Wallis (Salisbury). There will be no shortage of works of art at all price points, and no doubt some discoveries too.

Scholar’s rock (18th century or earlier), China. Eskenazi (price on request)

The range of gallery exhibitions is impressive. Eskenazi, for instance, offers ‘Room for Study: Fifty Scholars’ Objects’. This includes items essential to the studios of the highly educated ‘literati’, court officials who effectively governed China from the Han to the Qing dynasties, along with archaic ritual bronzes reflecting the taste of these scholar-poets for antiquities. Functional implements relating to the practice of painting and calligraphy range from the relatively humble to exquisitely worked pieces in jade, bamboo, cloisonné enamels and lacquer. Most immediately arresting are the mounted rocks and roots of fantastical shape, admired as microcosms of the natural world. Prices $5,000 to over $1m.

Dragons prevail in Ben Janssens’ show ‘Mythical Beasts’. Its earliest exhibit is a bronze mount from the beginning of the Warring States period in the fifth century BC, modelled as the stylised head of a dragon ornamented with serpent-like creatures, while one of its latest is an 18th-century black-lacquer dish from the Ryukyu Islands inlaid with brilliantly opalescent mother-of-pearl. Such pieces were used by the Ryukyu court but also sent as tribute to the Chinese. Prices £1,500–£48,000.

Dish (18th century), Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Ben Janssens Oriental Art (£12,000)

Appropriately, perhaps, many of the Asian works of art on offer in London reflect the relationship between East and West, tradition and innovation. ‘Treasures’, at Jorge Welsh Works of Art, features some of the most unusual and high-quality Chinese export works of art custom-made for Westerners. Most striking is a Qianlong copper runic calendar staff made before 1753 that was less a walking aid or even a portable timekeeping device than it was a swaggering status symbol, and one of only five staffs made after a Swedish model known to survive. Bowling along its length is an engaging retinue of animals, real and mythic, fish, figures, and much besides. It bears a six-figure price tag.

In dramatic contrast in scale is the diminutive Hu vase at Littleton & Hennessy Asian Art decorated in falangcai or ‘foreign’ enamels that stands only 5.7cm high. Made in the imperial workshops in Beijing, it bears the Qianlong imperial seal mark and is of the period (£100,000).

Hu vase (Qing Dynasty, Qianlong period [1735-96]), China. Littleton & Hennessy Asian Art (£100,000)

‘Inking Identity: Calligraphy of the Obaku School’ at Sydney L. Moss explores the fascinating fusion not of East and West but of China and Japan in the early 17th century. At the request of Chinese traders in the port of Nagasaki, Buddhist monks from Fujian emigrated to Japan, transmitting along with their teachings the tea ceremony, painting and calligraphy. Their hybrid Zen sect became known as Obaku, and its calligraphy is renowned for its boldness and fluidity. Included is a very rare pair of six-fold screens by the monk Ingen Ryuki (1592–1673).

Gregg Baker Asian Art brings together work by the revolutionary Japanese ceramic art group Sodeisha (‘Crawling through Mud Association’), the first to make non-utilitarian ceramics in Japan, with the abstract masters Key Sato (1906–78) and Kokuta Suda (1906–90), whose use of sand, pebbles and gesso gave their work a ceramic-like appearance. Prices £2,500–£70,000. Simon Pilling focuses on urushi – lacquer from Japan’s pre-modern period to the 21st century – and Hanga Ten on contemporary Japanese printmakers.

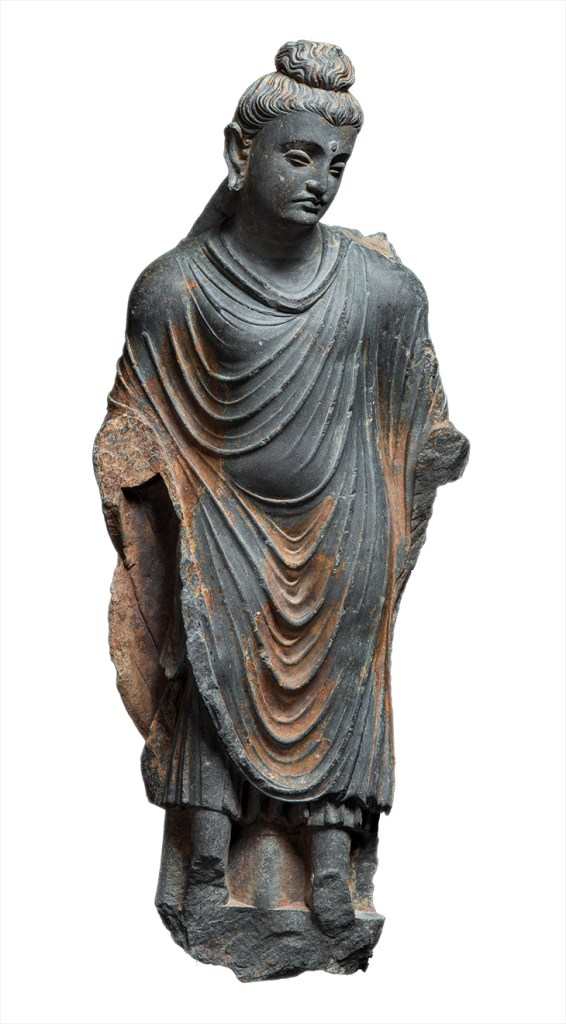

Standing Buddha (2nd/early 3rd century), Gandhara. John Eskenazi (price on request)

The Buddhist art of Gandhara fused ancient Indian and Hellenistic traditions. A sensitively carved, high-relief grey schist standing Buddha of the 2nd or 3rd century at John Eskenazi marks the transition between narrative panels and freestanding iconic images. Tantra, Jain and Hindu ritual art is in the spotlight at Joost van den Bergh.

Octagonal tray (early 18th century), norther India (Mughal). Simon Ray (price on request)

Simon Ray’s panorama of the Indian and Islamic worlds embraces everything from Safavid tiles to a dazzling 18th-century Mughal silver-gilt and champlevé enamelled octagonal tray and a watercolour showing the processes of a Kashmiri shawl-weaving workshop, probably made for the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Jacqueline Simcox offers textiles themselves – costumes, religious items, wall-hangings and decorative furnishings of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

One of the most striking differences between the earliest and more recent iterations of AAL is the number of galleries presenting contemporary Asian art. Not all focus on traditional techniques and idioms, as He Xi’s show at Jonathan Cooper demonstrates. So, even more emphatically, does Song Dong, whose show at Pace has been timed to coincide with AAL. His multimedia ‘Same Bed Different Dreams’ treats themes such as memory, impermanence, consumerism, waste and the urban environment as well as returning to the East-West dynamic in our increasingly globalised world.

Speed and Passion (2019), He Xi. Jonathan Cooper (price on request)

Asian Art in London takes place at various venues across the city from 31 October–9 November.

From the November issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?