‘It is not sufficient to be artistic and a good craftswoman,’ said Ethel Mairet in an interview in 1932. ‘It is necessary to have a good head for business and to follow the trend of what the public wants.’ Mairet was a pioneer in craft: singlehandedly, she revived handloom weaving and natural dyeing in Britain. From her home and workshop in Ditchling, where she lived from 1916, she worked as a weaver, researched vegetable dyes, taught, wrote books, and sold her modern designs to industry. In 1939, she became the first woman to be awarded a Royal Designer for Industry.

Mairet’s comments capture the creative energy of the interwar period, when designers and artisans were deeply engaged with debates surrounding the future of craft in an industrialised world. The desire for objects that were ‘sufficient, strong, well-made, and beautiful of [their] kind’, as described by the horticulturalist and writer Gertrude Jekyll – owed much to the Arts and Crafts movement, which prized hand skills over cheap factory production. But Mairet wasn’t nostalgic for the pre-industrial society imagined by Ruskin and Morris: she was a modern maker, with a modern audience in mind. Like the other women whose work is presented in the Ditchling Museum’s small but detailed exhibition, she set out to promote traditional techniques, but to make a living from them, too.

Bowl (c. 1934), Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie. Courtesy Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft

The exhibition, arranged around the museum’s permanent collection (largely the work of Eric Gill, who set up shop in Ditchling in 1907), draws attention to the breadth of crafts in which women worked, including silversmithing, weaving, hand-block printing, textile design and ceramics. The works reveal innovation as well as technical skill. Potters Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie and Denise Wren experimented with glazing: Pleydell-Bouverie trialled hawthorn and ash glazes, so that her vessels, narrow-necked vases and delicate bowls with surface patterns combed on to the clay, appear earth-coloured, ‘like pebbles and shells and birds’ eggs and the stones over which moss grows’; Wren used vibrant commercial glazes to exaggerate her unconventional slab-built pots. For Catherine ‘Casty’ Cobb – who began working with metal in the 1920s – jewellery could be crafted from found objects, including the clasps used in her father’s bookbinding business. One necklace, a series of blown glass spheres connected by looped silver wires, is both delicate and globular, like a succession of tiny lightbulbs. Cobb was also known for her ‘pique’ work, in which she drilled pinprick holes into ivory pieces (a cruet set, napkin rings, cutlery) and filled them with silver thread. She was playful with materials, often resourceful, and so challenged the distinction between domestic and art objects. When confronted with silver shortages during the First World War, she used steel instead.

Necklace (1934), Catherine Cockerell/Cobb. Courtesy Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft

The area of the exhibition given over to textiles shows the extent to which women, connected through networks of teaching and shared knowledge, supported and promoted each other’s work. Elizabeth Peacock, who sold her weaves to Elsa Schiaparelli, was a student of Mairet’s and lived with her at Ditchling; Enid Marx, who set up her own printing studio, began her career as an apprentice of Phyllis Barron and Dorothy Larcher. Barron and Larcher’s textiles, a series of refined geometric shapes in repeat, hang impressively in the gallery. Using a limited palette of indigo, slate grey and cutch brown (they learned the techniques of natural dyeing from Mairet), they worked with cotton, velvet, and organza, and used everyday items, such as combs, to print with. Despite their close partnership, individual styles emerge: Barron’s bolder line; Larcher’s gentler nature-inspired patterns. They worked hard to sell their work: account books and order forms show the mechanics of finance, along with submissions to industrial fairs and exhibitions, and letters to private clients providing swatches and samples.

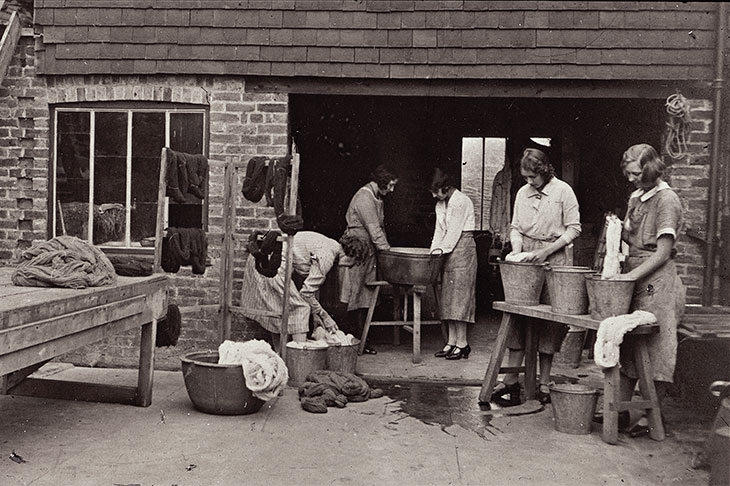

Barron and Larcher’s workshop. Courtesy Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts

Domestic life often formed part of the creative vision. Wren and Rita Beales chose a rural life: Wren, at Potters Croft in Surrey, a purpose-built live-work space that blended craft with small-scale agriculture; and Beales in the Cotswolds, where she lived self-sufficiently and produced her best work. Partnerships were both creative and queer. In 1935, Marx set up home with the historian Margaret Lambert, with whom she collected English folk art and lived for 60 years. Similarly, in 1922, Peacock and Molly Stobart, a local farmer, built ‘Weavers’ – house, workshop and smallholding – at Clayton, near Ditchling; the pair were to remain there for the rest of their lives. ‘I am rather curious to see Miss Peacock’s establishment,’ wrote one of their apprentices to his mother, describing the ‘slight delicate prim little person’ who lived with ‘a farmer who has never worn a skirt’, red-faced and short-haired. ‘They get along splendidly it appears.’

‘Women’s Work’ is at the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft until 13 October.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?