Most would associate Gustav Klimt above all with The Kiss, the culmination of his ‘golden phase’ in 1907, and with the Vienna Secession, which he co-founded ten years earlier. But it is often forgotten that, by the turn of the 19th century, Klimt had already enjoyed a fruitful career of more than two decades, principally working on public commissions alongside his brother Ernst Klimt and his friend Franz Matsch, who formed a company together in 1879. Their work took them far beyond the Austrian capital; today, some of the best insights into the young artist’s development can instead be found further afield, across the former Austro-Hungarian empire.

The city of Rijeka, Croatia, is a case in point. It’s home to an ornate theatre, one of many designed across Austria-Hungary by the prominent Viennese architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer in their distinctive neoclassical style, including three in Croatia (the others are in Varaždin and Zagreb). Irena Kraševac, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Art History in Zagreb, explains: ‘Of the three theatres, the best preserved in its original form is the one in Rijeka, which opened in 1885. The architects mainly engaged Viennese artists in their projects, so they entrusted the decoration of Rijeka’s theatre to the then-young painters Gustav Klimt, Ernst Klimt and Franz Matsch.’

The artists were commissioned by Fellner and Helmer to complete nine large canvases for the auditorium of the theatre, depicting mythical and historical scenes; three were completed by Klimt himself – Saint Cecilia, Orpheus and Eurydice and Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The works have remained in the auditorium to this day – little known beyond Rijeka, except to Klimt scholars. Now, on the back of its designation as European City of Culture in 2020, Rijeka is hosting ‘Unknown Klimt – Love, Death, Ecstasy’, which offers the first-ever chance to see all nine paintings up close. Newly restored, they are on display in what’s known as the Sugar Refinery Palace – a grand, baroque building, built in the 18th century as a sugar factory, that has recently been renovated to house the City Museum, which moved there in November last year.

Deborah Pustišek Antić, the curator of the exhibition, tells me that the Klimt brothers and Matsch likely painted the works in a studio in Vienna. ‘However, this does not mean Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch did not visit the theatre in Rijeka,’ she says. ‘Nearby Opatija was a favourite holiday destination at that time – it is easy to imagine that, on a visit to Opatija, the artists might have continued to Rijeka, to see how their works, in their sumptuous stucco frames, chimed with the ambience of the theatre.’

For Kraševac, the works are of significant value to artistic heritage in Croatia. ‘There are not many early Klimt paintings in Vienna,’ she says. ‘Works from this phase can be found in the Czech cities of Karlovy Vary and Liberec, and in the Romanian royal castle of Peles. But these paintings from Rijeka really do stand out – above all for refinement in their treatment of female faces, as witnessed with the beautiful characters of Eurydice, St. Cecilia and Cleopatra.’

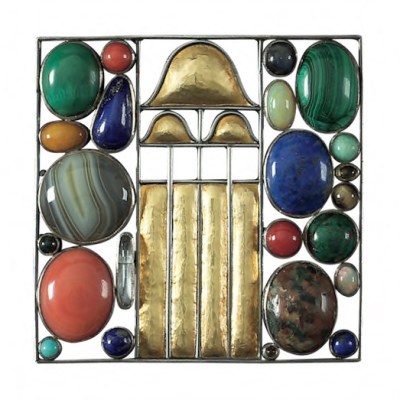

Mark Antony and Cleopatra (1885), Gustav Klimt. Croatian National Theatre Ivan pl. Zajc, Rijeka. Photo: Petar Fabijan; © City Museum of Rijeka

Alfred Weidinger, director of the OÖ Landes-Kultur museum in Linz and an authority on Klimt, explains why young artists like Klimt might have found work outside the Austrian capital. After the construction of the Ringstrasse in the mid 19th century, decorative painters in Vienna found themselves in great demand. As a result, Weidinger says, ‘new business opportunities opened up for young artists in other parts of the Habsburg Empire; these young artists were able to deliver quickly, and they were affordable. Klimt’s work was rather academic at that time – close to the so-called Viennese late historicism – but his theatre-paintings show early signs of Viennese art nouveau, especially in his figurative representations. He drew on the skills he developed with these large-scale commissions for his later work on the Faculty Paintings, the Beethoven Frieze and the Stoclet Frieze.’

Ana Rušin Bulić, a senior conservator-restorer at the Rijeka Department for Conservation, has worked alongside her colleague Goran Bulić on the restoration of the three paintings by Gustav Klimt exhibited in Rijeka. Having worked to remove accumulated deposits of dirt and correct previous attempts at retouching the painting, Rušin Bulić explains that the richness of Klimt’s palette and the lightness of his brushstrokes have come to the fore. ‘It is exciting, and moving, to observe Klimt’s early works, knowing the later ones so well,’ she says. ‘Klimt painted these paintings at a very young age with extreme ease and confidence. It is interesting to recognise in them the genius of a painter who was preparing to push the boundaries of his time.’

Orpheus and Eurydice (Allegory of Poetry) (1885), Gustav Klimt. Teatro Comunale, Rijeka. Photo: Petar Fabijan; © City Museum of Rijeka

The exhibition of this world-renowned modern master is undoubtedly the artistic event of the year in Rijeka, and represents something of a cultural awakening for the city after the challenges of the pandemic. ‘Whoever wants to know something about me,’ Klimt once said, ‘ought to look carefully at my pictures and try to see in them what I am and what I want to do.’ Here, then, is an unparalleled opportunity to get to know the artist as a young man.

‘Unknown Klimt – Love, Death, Ecstasy’ is at the City Museum of Rijeka until 20 October.