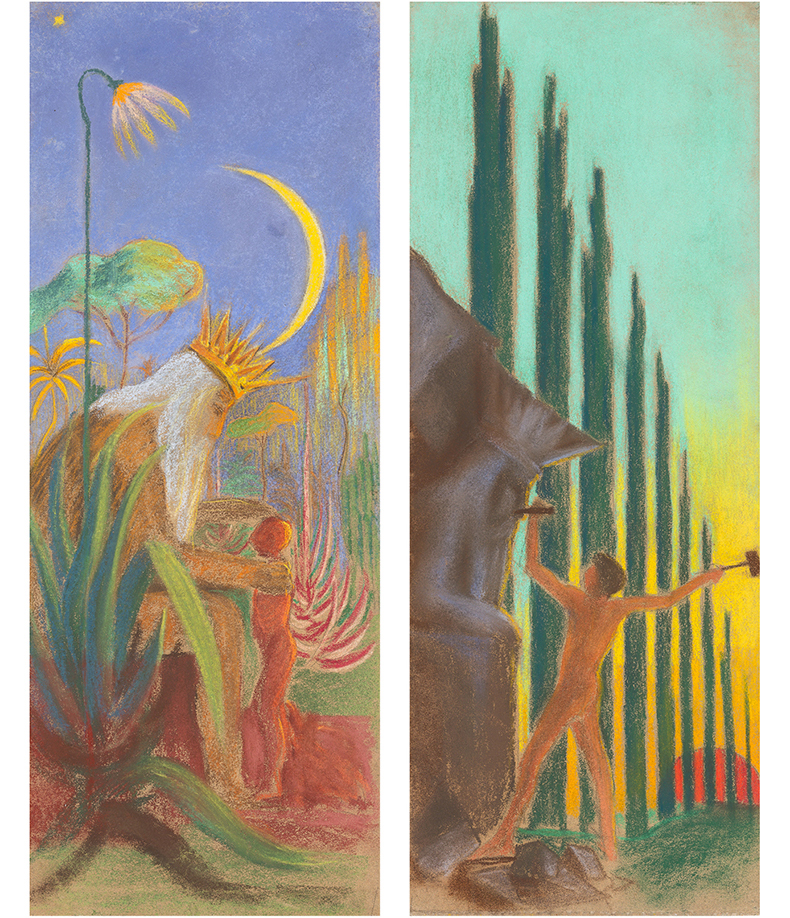

‘M.K. Čiurlionis: Between Worlds’ opens with Rex (Sketch I and Sketch II) (1904), a small pastel design for a stained-glass diptych. In the first panel, a bearded, godlike king sits in a verdant garden, sculpting a figure of a man out of red clay. In the second, a man stands, naked, chiselling an icon of the same king out of dark rock. It’s a fitting choice to introduce an artist for whom the spiritual and physical worlds reflected and required one another – with painting a means of finding a path between them.

Rex (Sketches I and II from the diptych for stained glass) (1904), M.K. Čiurlionis.

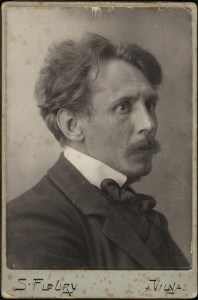

Until curator Kathleen Soriano and the Dulwich Picture Gallery undertook the task, there had never been a major exhibition of Čiurlionis’ work in the UK. But he is a national treasure in Lithuania; all of the works on display here have been loaned from the M.K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum in Kaunas. Born in 1875, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis was a successful composer (a selection of his compositions plays in the mausoleum at the Dulwich, notes echoing through the exhibition galleries) and only turned to painting in his late twenties, studying at the Warsaw School of Drawing and then moving to the same city’s School of Fine Arts when it opened in 1904. Between 1902 and 1909, he created a beguiling body of work before his death from pneumonia in 1911, at just 35 years of age.

M.K. Čiurlionis, photographed by S. Fleury in 1908. Courtesy M.K. Čiurlionis Museum of Art, Kaunas

In Čiurlionis’ time, Lithuanian life was heavily influenced by Poland and Russia. Russia had occupied the country since the early 1800s, but strong nationalist sentiment and cultural revivalism persisted, especially among the working class. Čiurlionis was a fervent champion of Lithuanian independence (which was eventually gained after the First World War) and in his visual work he expressed this passion through symbols drawn from folklore. Rex – the godlike king from that opening sketch – appears frequently, along with birds (associated with the soul), forests (places of comfort and companionship) and stars (‘sisters in the sky’). They are joined by myriad other mystical and cultural motifs: angels, the Zodiac, pyramids, stupas, torii – the list goes on. The artist drew on stories that he gleaned from sources as varied as Christianity, the ancient Indian Vedas and the cult of Prometheus. He also incorporated multiple artistic influences – symbolism was an important touchstone, while, reflecting European japonisme of the day, one painting of 1908 is a clear homage to Hokusai’s great wave. In his work, all this jumbles together into a deeply personal pantheon.

Creation of the World. III (1905–06), M.K. Čiurlionis. Courtesy M.K. Čiurlionis Museum of Art, Kaunas

Holding all this together is Čiurlionis’ distinctive style. Almost every work at the Dulwich is small in scale, painted in pastel or tempera on a paper or cardboard ground. While the reasons were partly pragmatic (Čiurlionis struggled to sell and fund his work), the effect is to imbue the artist’s kaleidoscopic worlds with a sense of intimacy, like domestic icons. They share a subtle palette best highlighted in his dreamlike series, Creation of the World I–XIII (1905–06). This visual creation story (‘not of our world according to the Bible,’ the artist wrote, ‘but another, fantastic world’) unfolds over 13 acts, its colours transforming from bruised blues and purples through soft-glowing pinks, ochres and misty greens as light and life burst into being.

Sonata No. 5 (Sonata of the Sea). Finale (1908), M.K. Čiurlionis. Courtesy M.K. Čiurlionis Museum of Art, Kaunas

Creation of the World is brought alive by brushwork; Čiurlionis uses tempera with a fluid dynamism that characterises his depictions of the natural world. In other works, he employs more regimented techniques. The triptych Sonata No. 5: Sonata of the Sea (1908) contains hundreds of bubbles, massing together into vast ocean swells. In Sonata No. 7: Sonata of the Pyramids (1909) the paint is applied in marching horizontal lines, punctuated by tall, thin columns and palms. Sonata No. 6: Sonata of the Stars (1908) features meandering lines like unruly musical staves.

There is a clear musical element to Čiurlionis’ paintings – even those whose names are less of a giveaway. Their rhythmic underlying compositions hold and give way to intuitive bursts of colour and curlicues of paint. In his Winter I–VIII series (1907), visual references drop away, trees and plants all but disappearing as if into heavy snow before eventually coalescing into more decorative forms.

The exhibition introduces us here to the argument, first proposed by critic Aleksis Rannit in 1949, that Čiurlionis beat Kandinsky to abstract painting. It is an interesting theory, unlikely ever to be fully resolved. Kandinsky was certainly aware of Čiurlionis’ work (in 1910 he invited the Lithuanian to participate in the New Munich Artists Association exhibition in Munich), but whether the latter really intended any of his paintings as ‘pure abstraction’ when his Winter series is so clearly distilled from natural forms is open to question. Besides, there are other artistic precedents that pre-date both artists – for example Hilma af Klint’s 193 Paintings for the Temple (1906–15). As interesting, perhaps, would have been for the exhibition to expand at this point on how music helped both artists create powerful painterly languages only loosely dependent on the physical world.

Rex (1909), M.K. Čiurlionis. Courtesy M.K. Čiurlionis Museum of Art, Kaunas

If Čiurlionis were experimenting with abstraction, he was hardly wedded to it; the final works in the show are among his most figurative and narrative. Mystical cities rear into view, populated by pensive angels, ghostly warriors and brooding demons. They appear almost as stage-sets for the artist’s vast imagination. It all culminates with an uncharacteristically large tempera on canvas, Rex (1909). At the centre sits the king, enthroned above a globe and a monumental altar in the middle of a vast sea. The altar’s flame casts his shadow high into the sky, where it looms over a visionary procession of earthly, celestial, and heavenly realms. Mountains, cities and clouds give way to comets, planets, stars, and ranks of attendant angels. It’s a climactic painting, seemingly trying to pull the full scope of Čiurlionis’ spiritual universe together in one sphere. In doing so, it loses something of the peculiar charm and mystery of his other works. But it brings us back to the subject of that first pastel sketch – to the mysteries of creation and the attempt to bring spiritual and physical worlds back together through art.

Angels (Paradise) (1909), M.K. Čiurlionis. Courtesy M.K. Čiurlionis Museum of Art, Kaunas

‘M.K. Čiurlionis: Between Worlds’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 12 March 2023.