The unveiling this April of previously unseen works by Anselm Kiefer represents a bittersweet moment for Copenhagen Contemporary (CC). On the one hand, an artist of Kiefer’s undoubted pedigree is a significant coup for an institution still in its infancy. On the other, the exhibition opens just eight months ahead of the scheduled closure of CC’s current space. Most believe that CC will continue its impressive programme from a new home, but with nothing yet publicly confirmed, the future remains uncertain.

CC is, for the moment, located within the vast former paper warehouses of Papirøen (Paper Island) right in the centre of Copenhagen. Between February 2014 and May 2016, the space provided a temporary home to a science centre called Experimentarium, while its previous premises underwent renovation. When Experimentarium returned to its long-term home, 18 months remained until the buildings at the Papirøen location were scheduled to be demolished and replaced with residential developments. With admirable alacrity, CC jumped at the opportunity to take over the 3,400 square-metre space, and opened its inaugural exhibition, a solo show for Carsten Nicolai, in July 2016.

CC – an independent institution that receives funding from a range of private foundations – is something of a rarity in Denmark, where most major arts institutions receive significant public funding. It was founded by – among others – Jens Erik Sørensen, formerly of ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, and Jens Faurschou, owner of the Faurschou Foundation, a private contemporary art institution which has venues in Copenhagen and Beijing. Supporters include numerous Danish foundations and private donors.

It is not only its organisational structure that sets CC apart, but the nature of the space. Several of Copenhagen’s larger city centre arts spaces are in architecturally complex venues: Kunsthal Charlottenborg is housed in a 17th-century baroque palace; Nikolaj Kunsthal is in a 20th-century reconstruction of a medieval church. Both have their strengths – Charlottenborg is currently showing powerful film works by Korakrit Arunanondchai in its comfortable auditorium, while Nikolaj’s large, arched nave contains a video installation by Julian Rosefeldt that responds perfectly to the surroundings.

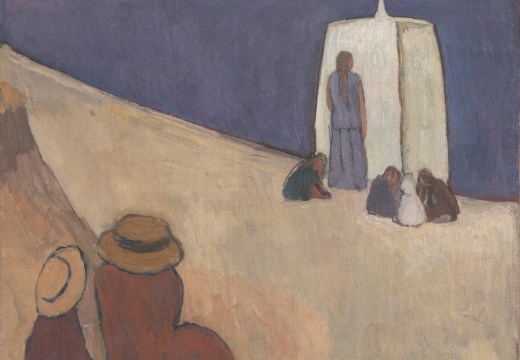

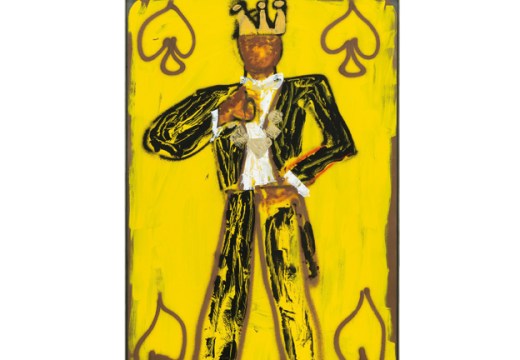

But such spaces do provide a challenge. CC, by contrast, offers something of a blank canvas: a big, simple, versatile space with limited vestiges of its industrial past. Georges Armaos, of Gagosian gallery, tells us that it was upon visiting the space in person that Kiefer became especially enthusiastic about exhibiting there. Armaos is also keen to emphasise the aesthetic similarities between Copenhagen Contemporary and Kiefer’s studio, a 35,000 square-metre former warehouse at Croissy-Beaubourg, 25 kilometres outside Paris. Transplanted from one warehouse to another are four full-scale reproductions of fighter jets, three in lead and one in zinc, as well as four vast ‘desert paintings’, strewn all over with beetle-black sunflower seeds.

As well as attracting big-name artists – Bruce Nauman and Céleste Boursier-Mougenot have also shown there; Yoko Ono currently has a work installed on the terrace – Copenhagen Contemporary has also opened up other opportunities. CHART art fair, for example, launched in 2013 to champion the best of Nordic art (and, more recently, design too). For 2017, as the fair continues to expand, a significant section will be held at CC. ‘CC is a unique venue,’ explains Simon Friese, director of CHART. ‘The placement on the harbourfront in large industrial buildings, formerly used for storing paper, makes it an ideal exhibition space for big, technically demanding installations of contemporary art which existing institutions have difficulty accommodating.’

Copenhagen Contemporary. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Here Friese touches on another important aspect of CC that has helped pull in the crowds: its location. In many cities these kinds of ex-industrial arts spaces are located well out of town. Think of Pirelli HangarBicocca, in an old factory complex on the outskirts of Milan, or Thaddaeus Ropac’s old ironworks in the Paris suburb of Pantin. Copenhagen’s most prominent contemporary arts space, Louisiana, is some 35 kilometres north of the city. David Risley, one of the city’s best-known gallerists, relocated from the commercial gallery hub of Bredgade in the centre to a larger space further out.

CC, meanwhile, located right by the water, is a highly visible presence in everyday city life. The new inner harbour bridge has improved access for pedestrians and cyclists, while the presence next door of a bustling indoor street food market also helps to explain CC’s impressive appeal. 60,000 people have visited since its opening last summer, 43 per cent of whom have been aged between 19 and 29 – the perfect demographic for art marketers. The team at CC are quietly delighted: ‘I think we have had a very positive response from both colleagues, the press and the visitors,’ says senior curator Jannie Haagemann. ‘We have had the best reviews of all our shows, and a very large number of visitors.’

Installation view of For Louis–Ferdinand Ceéline: Voyage au bout de la nuit at Copenhagen Contemporary, Anselm Kiefer, 2016. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

All of which makes CC’s imminent departure something to be lamented. Haagemann and her team are adamant that CC will be able to continue its ambitious programming from a new venue, but whether they will be able to find somewhere similarly large, versatile, accessible (and preferably next to a plethora of delicious food options) remains to be seen. Perhaps the city’s meatpacking district, now home to an array of restaurants as well as cutting-edge galleries like V1 and Eighteen, might be one possibility. ‘We have been presented with several options that we are now considering,’ says Haagemann.

In the meantime, locals and visitors should be sure to visit CC before the current space closes at the end of 2017. In addition to the Kiefer exhibition is a complex installation by US artist Sarah Sze (until 3 September) and a video piece by France’s Pierre Huyghe until 21 May (which bears some thematic similarities to the Arunanondchai films at Charlottenborg). Then again, if Kiefer’s strewn sunflower seeds are the symbols of regeneration that many like to believe, then perhaps some of their potency will rub off on Copenhagen Contemporary, and the demise of one incarnation will lead inexorably to the rise of the next.

‘Anselm Kiefer’ is at Copenhagen Contemporary until 6 August 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?