1768 was a triumphant and a turbulent year for the British Empire. In February, the British managed to bring the Indian state of Hyderabad under their control; six months later, James Cook took to the seas in HMS Endeavour, his cartographical discoveries going on to lay the groundwork for the British colonisation of the Antipodes. But the American colonies in Boston were growing mutinous, and the prime minister William Pitt the Elder, who had overseen a world-historical expansion of the Empire, was in parlous health.

It was in the same year that the British government established its first secretary of state for the colonies and a group of ambitious artists founded the Royal Academy of Arts under the aegis of George III. At the time, these actions must have seemed entirely unrelated. But they both seem now like projections of confidence, attempts to formalise and systematise British cultural ambitions.

The exhibition ‘Entangled Pasts, 1768–now: Art, Colonialism and Change’ is the Royal Academy’s attempt to tug at the threads of its own complicated history. ‘Entangled’ alludes not just to British entanglements abroad but to the inextricability of the country’s most prestigious artistic institution from British imperial thinking. Many of the works on display date from the colonial period and for various reasons would be considered ‘problematic’ today, but the show isn’t all self-reproach. The older paintings, which largely date from the 18th and early 19th centuries, are surrounded by the work of postcolonial and contemporary artists, many of whom are Academicians or have shown at the RA before.

Installation view of The First Supper (Galaxy Black) (2023) by Tavares Strachan at the Royal Academy, London. Glenstone Museum, Potomac. Photo: Jonty Wilde; courtesy the artist and Perrotin; © the artist

A complex project, then – but that doesn’t stop the exhibition from projecting a confidence of its own from the start. The show begins in the Annenberg Courtyard, in front of the Academy building, with Tavares Strachan’s The First Supper (Galaxy Black) (2023). A bronze recasting of Leonardo’s Last Supper with black patina and gold leaf, it has Black icons such as Zumbi dos Palmares, Haile Selassie and Sister Rosetta Tharpe striking poses behind a long table. It’s not the first time a sculpture has been placed in conversation with the magisterial bronze rendering of Joshua Reynolds that stands outside the institution’s doors; it’s not even the most confrontational example. (I’m thinking of one of Barry Flanagan’s briefly installed Nijinski Hares, which, when seen from a certain angle, was about to sock the Academy’s first president in the face.) But at more than nine metres wide, Galaxy Black gives visitors a taste of the scale of the exhibition to come – a show that spreads more than two and a half centuries of art history throughout a dozen galleries.

What is most pleasing about ‘Entangled Pasts’ is its inventive use of space. The exhibition begins proper in the ‘Octagon’ of the Main Galleries, where busts of eight renowned artists have long sat in recesses high above. But for this show, busts of Reynolds, Michelangelo and Raphael are hidden by mirrors that reflect Francis Harwood’s Bust of a Man (1758), an African figure hewn from black stone, which sits proudly at eye level in the centre of the room. The mirrors serve several symbolic functions: they establish the theme of reflectiveness, invert established hierarchies and, in a humanising move, place Harwood’s piece among versions of ourselves.

Bust of a Man (1758), Francis Harwood. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: © Royal Academy of Arts, London/David Parry

This density of ideas and images – complemented by several portraits of exclusively Black sitters and dramatised by muted lighting – gives way to a more expansive approach as the Academy begins to incriminate itself. The following room sheds light on the varied ways in which the Academy’s exclusively white members, including the Americans Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley, painted Black and Indigenous figures and white upholders of slavery. The curators wisely choose not to mount any particular arguments, simply presenting portraits and history paintings as part of a broad, contradictory picture. Some Black figures, such as the servant hastening to adjust the Prince of Wales’s belt in a portrait of c. 1787 by Reynolds, are presented as both deferential and impetuous, while others, most notably King Henry Christophe and Prince Jacques-Victor Henry of Haiti in a pair of portraits completed in 1816 by frequent Royal Academy exhibitor Richard Evans, carry themselves with regal splendour.

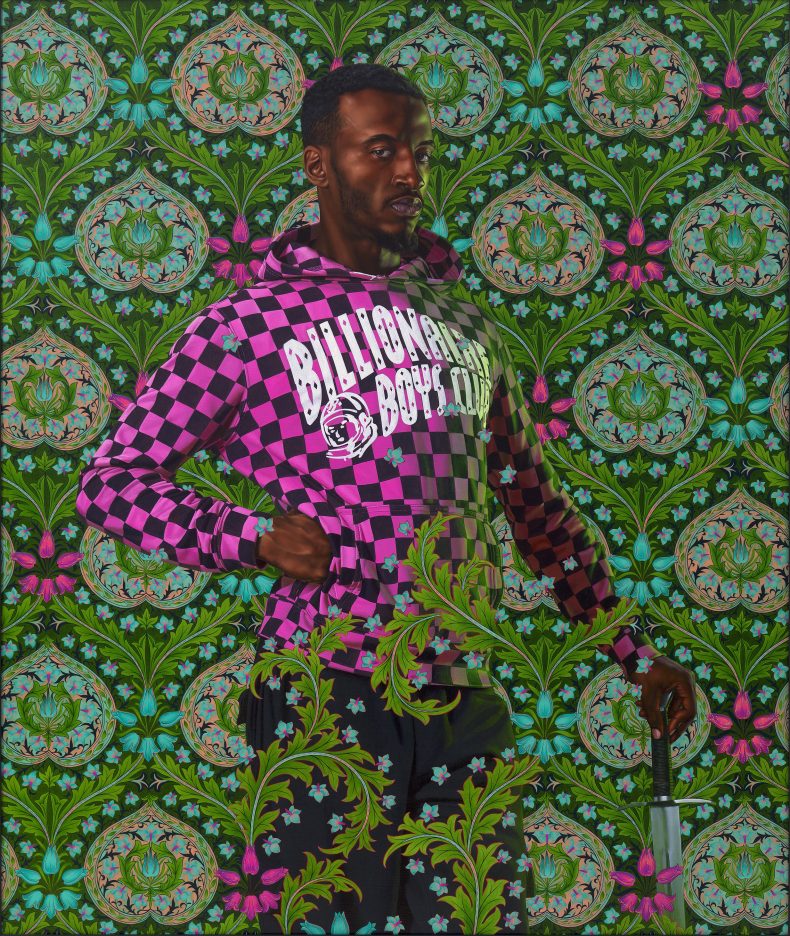

So varied are the portraits, in fact, that some of them risk making some of the contemporary works with which they are paired seem redundant. Kehinde Wiley’s Portrait of Kujuan Buggie (2024) – after Reynolds’ portrait of the cavalryman Captain Arthur Blake from 1769, which is curiously not on display here – is a painting of a proud young Black man standing in a black and pink chequered hoodie, leaning lightly on a sword, against a paisley-esque green background. But viewed near Evans’s portraits, this attempt at redressing underrepresentation seems less bold than may have been intended – perhaps even unnecessary.

Portrait of Kujuan Buggie (2024), Kehinde Wiley. Photo: © Royal Academy of Arts, London/David Parry; courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York/Roberts Projects, Los Angeles/Sean Kelly Gallery, New York and Los Angeles; © the artist

This is not so much a criticism of Wiley’s desire to depict Black figures in historical modes that had previously been mostly denied them as it is a question: by showing this portrait, what exactly is the exhibition trying to say? When it comes to representing the early decades of the Academy, the show seems to be in a bind: unable to solely perpetuate narratives of Black victimhood and subjugation, it is obliged to present Black figures, such as Henry Christophe, in positions of authority. This is no bad thing, but it has a strange flattening effect, as if to suggest that both kinds of representation are simply two sides of an art-historical coin.

It’s telling that the curators don’t seem entirely sure how to address Copley’s Watson and the Shark (1778), the most important loan of the exhibition. An immediately striking composition that depicts an attempt to save the young Englishman Brook Watson from a shark attack near Havana, it has a Black figure at its centre but in an ambiguous position. He is less active than his white crewmates but may be the crew’s most important member, holding as he is the rope that will save Watson. He seems paralysed by fear yet stands upright with impressive poise. In the audio guide that accompanies the exhibition, the curators acknowledge these contradictions. What they don’t ask is what it means for the Black man at the centre of a painting by a slave-owning Academician to be realised with more precision, realism and immediacy than any of the white figures around him.

Watson and the Shark (1778), John Singleton Copley. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo: © Royal Academy of Arts, London/David Parry

The Academy has set itself a tricky, perhaps impossible task. The more wide-ranging it appears to be – there are around 100 works on display – the more it seems to leave out. Though the show moves deftly between the 18th or early 19th centuries and the 21st, there are a total of four artworks made between 1879 and 1969, which, given that the exhibition is billed as ‘1768–now’, raises the question of what the Academy and its students and exhibitors were up to for the best part of a century. Or perhaps the art just isn’t any good?

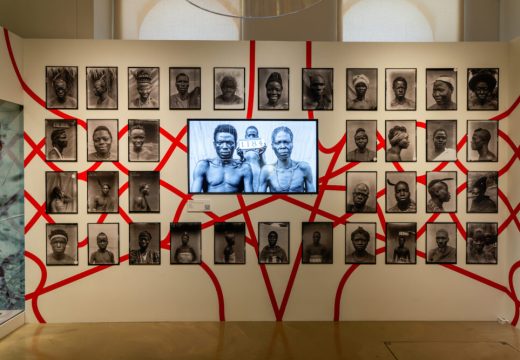

The internal logic of some of the galleries also falters at points. One room is devoted to ‘Sculpture and Photography’, but it is unclear why Isaac Julien’s Lessons of the Hour (2019–20), which comprises a film about Frederick Douglass and a set of collodion tintypes, is sharing space with Hiram Powers’ The Greek Slave (1862) and a series of sculptures by John Bell, besides the slavery connection. The impression given is that the curators weren’t sure where else to put these works and came up with a rubric retrospectively.

At their best, however, the organising principles work tremendously. ‘The Aquatic Sublime’, one of the final galleries, explores the perils of the voyage of slaves across the Atlantic, and includes several of the show’s most powerful works, including Frank Bowling’s three-metre-high abstract canvas Middle Passage (1970) and El Anatsui’s Akua’s Surviving Children (1996), an installation that conveys yearning, displacement and loss through a series of humanoid figures made from driftwood and metal. J.M.W. Turner knew how violent ocean voyages could be: his Whalers (c. 1845), in which blood gushes from a harpooned sperm whale, hangs nearby. All these themes are gracefully synthesised by John Akomfrah’s three-channel installation Vertigo Sea (2015), an act of commemoration and marine exploration that is arresting for every one of its 48 minutes.

Whalers (c. 1845), J.M.W. Turner. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

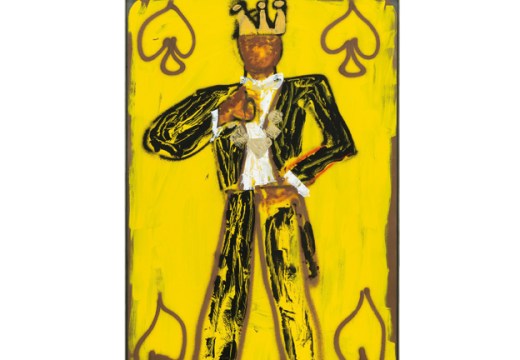

Again and again, the contemporary works are searing. Yinka Shonibare’s Woman Moving Up (2023) is a fibreglass mannequin ascending a neoclassical staircase, its balustrades casting ominous shadows. The figure is wearing a Victorian dress made of African textiles featuring Indonesian designs sold back to the African market. With a globe for a head and a posture that is abject and optimistic in equal measure, the mannequin says more about the contrivances of global trade networks and patterns of economic subjugation than a wall text ever could. And any ethnic-minority viewer who has been called by a Western name for ‘convenience’ will feel a jolt of recognition at Lubaina Himid’s Naming the Money (2004), in which two entire galleries are colonised by dozens of cut-out human-size figures, labels on their back relating stories of effacement and loss of independence: ‘My name is Akin / They call me Jack / I used to measure mountains / Now I measure the estate / But I have the sky.’

It’s in these sorts of curatorial coups that the exhibition is at its strongest. They are reminders that for all the institution’s uneven history when it comes to granting and denying platforms to certain groups of people, the Academy’s eye for talent has grown increasingly open to diverse sources of creativity. Akomfrah, Shonibare, Himid and other postcolonial risk-takers are Academicians now and the institution is richer for it. The status of these artists reflects the values of their era – just as the status of Reynolds, Copley, West and co. reflected theirs.

‘Entangled Pasts, 1768–now: Art, Colonialism and Change’ is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London until 28 April.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?