The catalogue has traditionally functioned as a supplement to the exhibition. On the page, even the most beautifully reproduced images serve mostly to remind us of the joy of viewing the originals. But the relationship is sometimes inverted. ‘Après Babel, traduire’ (After Babel, translate) at MuCEM in Marseille is a prime example. The underlying concept – exploring the history, culture and geopolitics of translation – is full of possibility, and the exhibition is undoubtedly interesting. But it is the catalogue that is the real triumph.

Perhaps this should not be surprising. ‘Je suis quelqu’un de livres,’ (‘I’m a book person’) said Barbara Cassin, the exhibition’s curator, at the press view. She is best known as a writer and philosopher, who served as director of the Collège International de Philosophie from 1986 to 1992. ‘Après Babel, traduire’ is full of books, but it contains many other beautiful things, too: maps and manuscripts, telescopes and astrolabes, and paintings by artists such as Cranach and Chagall, alongside pieces by Duchamp, Rodin, Bertrand Lavier, and Claire Fontaine.

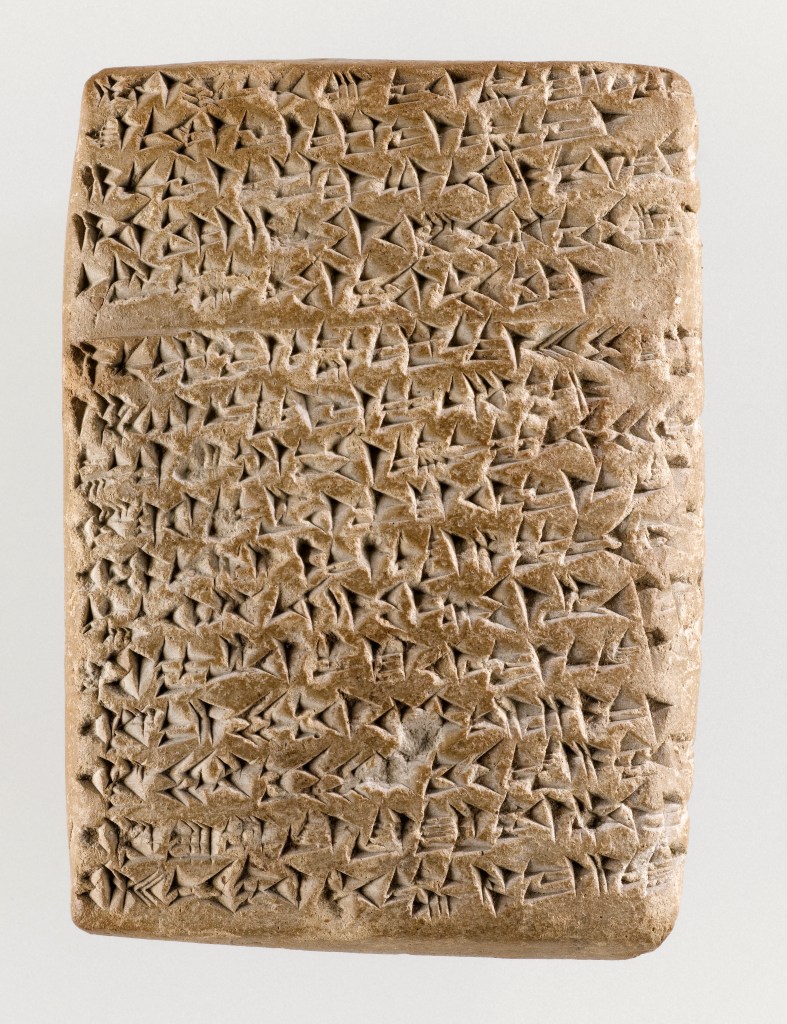

Letter of Amarna, (c. 1353–35 BC). Musée du Louvre, Paris; © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux

The exhibition is divided into three sections. We begin with the Babel myth and the exhibition’s key question: is the proliferation of languages a curse or an opportunity? The latter, argues Cassin, so long as there is translation. Cassin’s larger point is that, as nationalism rises against a certain homogenising (Anglophone) globalisation, translation offers a powerful model for an alternative, more responsible kind of citizenship. The second section traces the linguistic routes taken by certain important texts – especially religious ones; and the final section looks at the limits of translation: those nuances of meaning or sound or rhythm that always escape even the most sensitive of translators.

The exhibition contains many fascinating insights. We learn, for example, which languages others dismiss as nonsense, or impenetrably difficult. In English, we have ‘all Greek to me’ and ‘double Dutch’, but the French have four equivalents, more than anyone else: Turkish, Hebrew, Chinese, and Javanese. We’re shown the power of the African word Ubuntu (loosely, ‘humanity to others’ or ‘human kindness’) in the South African constitution. We learn too of the compulsory use of French in many areas of public life, implemented by the ‘Toubon Law’ in 1994. Finland has both Finnish and Swedish inscribed in its constitution – a reflection of the wealth and power of the country’s tiny Swedish-speaking minority. As the UK privatises legal interpretation services with disastrous consequences, this discussion of the language in which power speaks (and listens) could hardly be more timely.

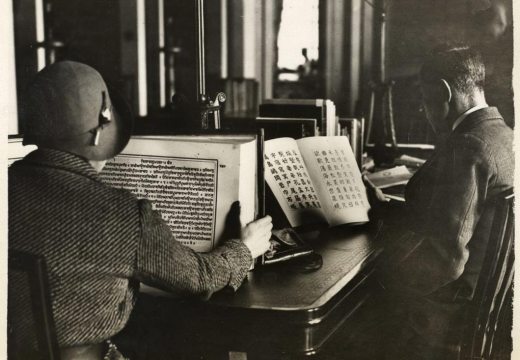

Elsewhere, highlights include the Amarna tablet, a 14th-century BC diplomatic letter written in Akkadian, a script of densely packed wedge-shaped marks; a Qur’an, Bible, and Torah displayed side by side to show the different ways that each monotheistic religion understood the translation of its sacred texts; a 1930s translation machine; and an interactive display that allows visitors to chart the geographical flow of writers and thinkers such as Karl Marx. Later, I especially like how Antoni Muntadas’s installation On Translation: The Games (1996) explores the strange ethical position occupied by the interpreter. One blames herself for directly translating an error made by her client and, in so doing, undermining the success of a business meeting. Could a machine ever have this kind of self-reflection?

Nonetheless, this is a flawed exhibition. Too many reproductions (of works by Bruegel and Blake, of the Rosetta Stone, of a pair of 6th-century Etruscan gold tablets) betray the priorities of an editor over those of a curator. A number of the inclusions function as examples of translated texts but don’t really provide much insight into the process of translation itself. A display of Tintin covers, for example, simply tells us that the books were translated a lot. It is only by reading the catalogue, which contains a wealth of nuanced ideas, that we discover why we should care. I would have also liked to see the exhibition draw out expanded definitions of both language and of translation. Unfortunately, the narrow focus on linguistic translation often leaves the wall text doing more work than the objects themselves.

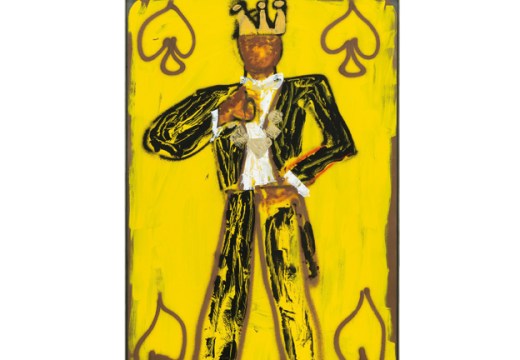

Self Portrait, (1646), Johannes Gumpp. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

The final work is a triple self-portrait from 1646 by Johannes Gumpp. On the left of the painting, we see Gumpp’s reflection in the mirror; on the right is the painted interpretation. The two are virtually identical, except for the positioning of the eyes and the unfinished collar. In the middle, the artist himself has his back to us. We never see the ‘original’; only those faces reflected back to us, represented, translated. Looking at the work is like watching a game of tennis, as my eyes flick back and forth from mirror to painting. Below, the painting’s deft composition is completed by the gaze from cat to dog and back again, each interpreting the other’s intentions. On the wall opposite are two questions: ‘Is there ever an original?’ and ‘What is identity?’ It’s a delightful finish, but one that also shows what might have been.

‘Après Babel, traduire’ is at MuCEM, Marseille, 14 December 2016–20 March 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?