A builders’ yard in a rural idyll, a serene river tributary overshadowed by a busy railway viaduct – the surroundings of Cample Line are full of pleasing contradictions. Established in 2016, this small gallery in the Scottish Borders is housed in a row of former millworkers’ cottages. But despite this modest setting, Cample Line is about as ambitious as it gets, not only seeking ‘mid-career visual artists who have an international track record’ but also collaborating with them to develop exhibitions of entirely new work – and thus shaping their professional trajectories.

Like many artists whose work has been shown here, Gabriella Boyd had never visited before she was invited to exhibit. But given that Cample Line encourages artists to respond to its building and rural setting, and that Boyd is preoccupied with interiors and interiority, it seems remarkable that this pairing had never been made before. Boyd paints on large linen canvases, which are sparsely placed across the gallery’s two levels. The whitewashed walls give definition to the pale palette of her paintings, the natural light of the windows (overlooking grass lawns and daffodils, rather than the light industry on the other side of the building) drawing us into the texture of the canvases. ‘I’m interested in shining a light on us being matter, as well as the spaces around us,’ Boyd explains in a documentary film that is part of the exhibition, ‘so the rooms becoming meat-like or skin-like or having the quality of an organism, or a lack of distinction [with] the meat of a person’.

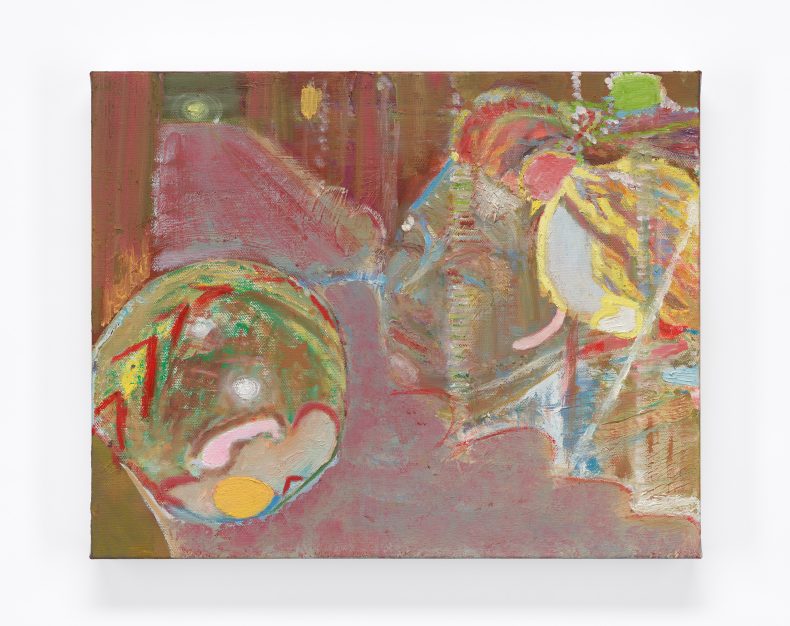

Two (2024), Gabriella Boyd. Courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery; © the artist

The show is titled ‘Presser’, which, Boyd explains, could refer to either a job title or the facilitation of touch. ‘So much of the work is about contact and lack of distinction between us and our surroundings and the people we are with,’ she says in the film. ‘I like the idea of choosing a title that’s not quite clear, either, of what it even is.’

Given her interest in collapsing boundaries, it is not surprising that Boyd is keen to combine abstraction and figuration. Across the room from the television showing the film is Chine (2024), which depicts a sensuous figure, somewhat liminal in its overlap with the background colours. It is overlaid with a skeletal bone structure and blocks of internal organs. These are reflected below in a series of flowers – a recurring motif in Boyd’s work – which stand within a huge, layered skirt that resembles a volcano erupting into the spine above. A raised arm presses home a sense of urgency, and we witness agency and vulnerability in a single, final gasp.

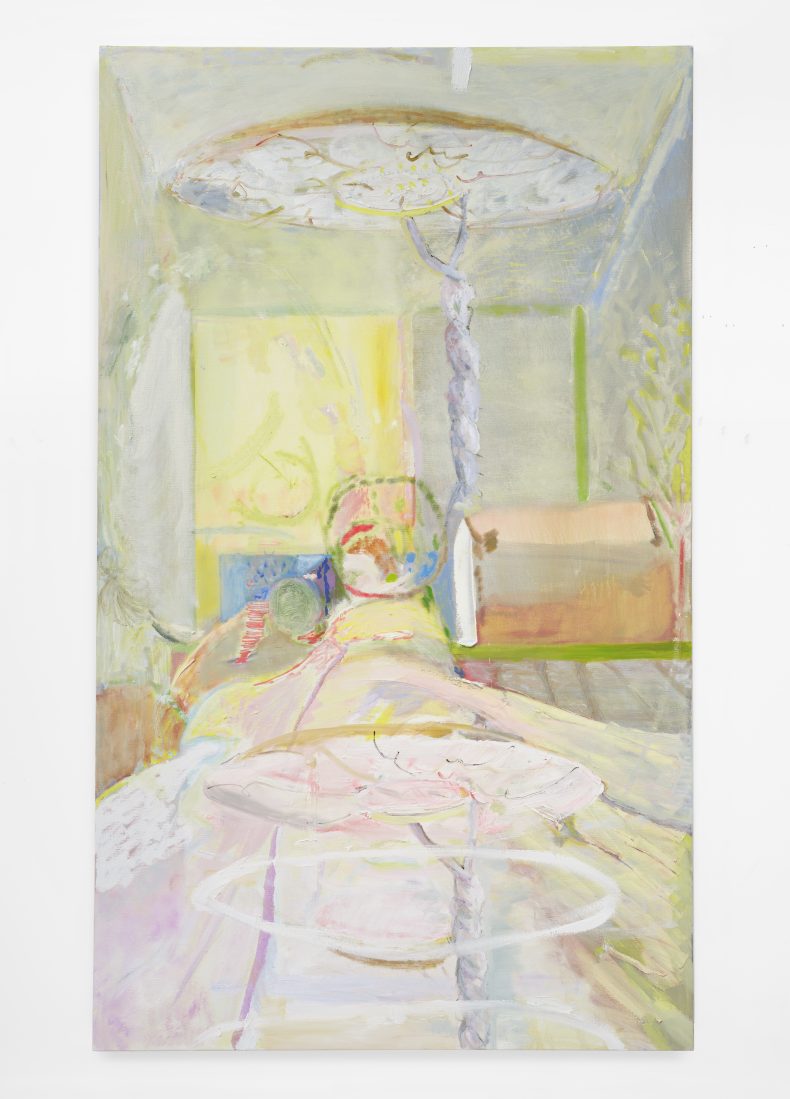

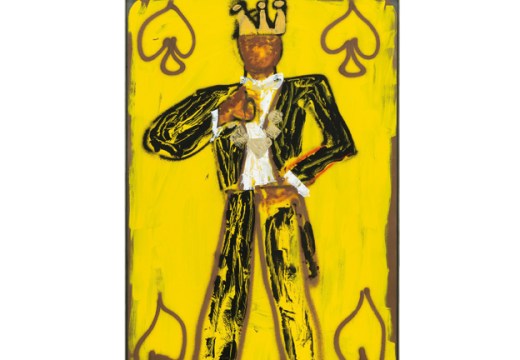

Retina (v) (2024), Gabriella Boyd. Courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery; © the artist

Boyd works on up to 10 paintings at a time in her London studio, so some have been in conversation for a while. Illness and recovery are present throughout the exhibition, both literally, in convalescing figures, and in a more abstract way in visions of hazy surroundings slowly beginning to make sense to the beholder. Among abstracted backgrounds we often see coils that nod to the way that perception itself can sometimes twist and become unclear: the backbone in Chine, the ‘tumour-like’ support structure in Brace (ii) (2022–24), and Retina (v) (2024), which shows a cord descending like an emergency help cable from an eye above a bed-bound figure.

‘Boyd’s paintings have this luminous quality of a world perceived with all the mass and unpredictable condition of our bodies,’ the curator and disability justice campaigner Yates Norton writes in a catalogue essay. ‘Surfaces are not simply things to touch, but things that touch in turn.’

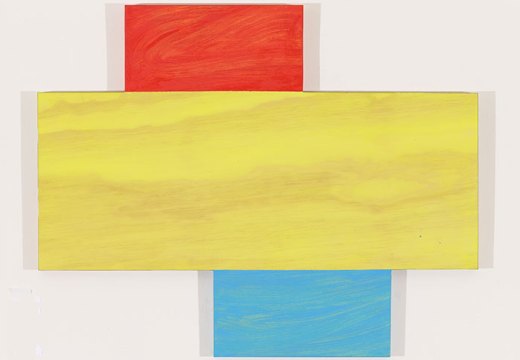

Telogen (2022–24), Gabriella Boyd. Courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery; © the artist

Just as we have acclimatised to Boyd’s linens and layers, this materiality is thrown into relief by the stripped-back beams of Cample Line’s upper level. Telogen (2022–24), one of the largest paintings on display, overlooks the whole room with a scene that reminded me of a particular work from Charlotte Salomon’s Life? or Theatre? (1940–42), which also features a thick swathe of bed linen and a somewhat spectral window – though the dismemberment and entanglement of body and interior in Boyd’s canvas produces a blurred, less tangible vision. Abstracted flower forms in the foreground suddenly give way to a convalescent in the background, who is being consoled by another figure. ‘Telogen’ refers to the resting phase of the hair growth cycle; roots of hairs are rendered here in the rays of light from the window, the flowers below and a plait-like series of chevrons on the back of the second figure. But the word conjures a sense of electric connection too – and, through the unrelated term ‘telegenic’, the ever-present motif of perception.

For Boyd, even in the throes of illness, the human form cannot be contained. In Telogen the artist has ripped out the heart of her convalescent and placed it in the foreground, where figuration begins to dissolve into abstraction. It underlines the fact that tension and conflict are essential to creating unity in her paintings, and reminds us that throughout ‘Presser’, amid the serenity of Cample Line, we are confronted with sites of struggle.

Carriage (2023), Gabriella Boyd. Photo: Josef Konczak; courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery; © the artist

‘Gabriella Boyd: Presser’ is at Cample Line, near Thornhill, until 2 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?