When the art historian Sir William Stirling-Maxwell travelled to Madrid in 1849, he made sure to visit the house of Javier Goya y Bayeu. Then ‘a civil old man of perhaps 60’, Javier was the custodian of his celebrated father’s drawings, bound into ‘three great books’. Assembled posthumously, the three volumes contained some images familiar to Stirling-Maxwell – including ‘the originals of many of the engraved Caprichos’ – but a great many more that he, along with most of Goya’s admirers, had never seen. A lifetime’s worth of studies and preparatory sketches accompanied by some 550 worked-up drawings from Goya’s ‘private albums’, they were a trove like no other. Stirling-Maxwell explored only one of the books, took detailed notes on two grotesque images of a repressive constable’s fate at the hands of his victims, and remarked, with some relish, on Goya’s taste for drawing ‘any dirty subject’ he saw.

Stirling-Maxwell must have been aware that his opportunity to sit down and leaf through the albums was a rare privilege, but he cannot have known just how rare. Not long after his visit, in the wake of Javier’s death in 1854, the three books were broken up and sold to aficionados across the Continent. While the Prado’s own holdings remain unparalleled, with 448 drawings entering the museum’s collection before the turn of the 20th century, many disappeared into private collections. Reassembled as new albums or sold on as individual drawings, they have remained dispersed ever since. Goya’s only true ‘sketchbook’, the ‘Italian Notebook’, would not come to light again until 1993; one set of 38 drawings, believed to have been destroyed during the fall of Berlin in 1945, resurfaced, finally, in 1996 at the Hermitage.

One Cannot Watch (1808–14), Francisco de Goya. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

While there have been a number of exhibitions including Goya’s drawings in the last few years – most notably the Hayward Gallery’s ‘Goya: Drawings from his Private Albums’ in 2001 and the Courtauld’s ‘Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album’ in 2015 – it is an index of the landmark nature of ‘Only My Strength of Will Remains’ that it reunites for the first time in some 160 years the two images Stirling-Maxwell described. Looking at them, you can see why he accounted them among the ‘best and most spirited’. Seen here alongside some 300 others from the Prado’s holdings and from private and public collections across the world, they remain an exemplary window on life in Goya’s world.

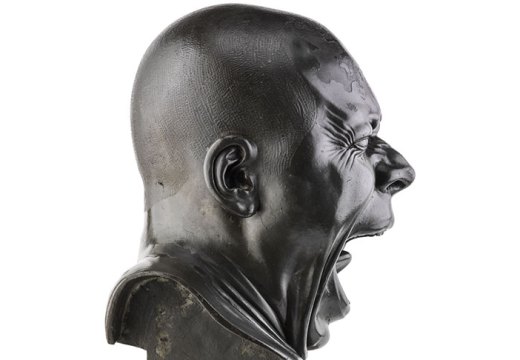

Based on events in Goya’s hometown of Zaragoza, the two drawings illustrate the constable Lampiños’ punishment with characteristic verve. In the first, captured by his victims, Lampiños has been sewn into the body of a dead horse: the only visible part of him is his head, emerging from the carcass’s arse, bawling in terror at a circling pack of dogs; pooled in the foreground is the broad slop of the horse’s guts. Having survived the night, he is shown in the second drawing receiving his coup de grâce. Viewed from behind, hoisted up above a scrum of the prostitutes he had persecuted, he has been stripped from the waist down and bent over, ready to receive an enema from a syringe the size of a man’s thigh. Pathetically, the clearest detail in the melee is his hand, flailing back desperately to protect himself. According to Goya’s caption, the syringe was full of quicklime.

![Death of the constable Lampiños […] (1812–20), Francisco de Goya. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DP800231.jpg?resize=730%2C1044)

Death of the constable Lampiños […] (1812–20), Francisco de Goya. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

For modern viewers familiar with The Disasters of War – only published in 1863, 35 years after his death – Goya’s fascination with man’s savagery to man will hardly come as a shock. Nevertheless, the cumulative effect of ‘Only My Strength of Will Remains’, in illustrating the chaotic and brutal comedy of life in Goya’s world, is astonishing. While there are tender drawings here, in particular from the ‘Sanlúcar’ album of the 1790s (Fig. 1), created during the period of Goya’s association with the Duchess of Alba, Goya’s jaundiced eye was able to find something cruel, stupid or both almost wherever he looked. And in the early 19th century, it did not have to look far.

One series from ‘Sketchbook C’ (1808–14), illustrating the victims of the Inquisition, is represented in full here. Their subjects are variously bound, humiliated, tortured or killed for crimes ranging from For Having Been Born Elsewhere, For Discovering the Motion of the Earth, or Since she went on talking […]; Goya’s caption to a drawing of a man tied and hoisted by the feet, head dragging on the ground, reads One Cannot Watch (Fig. 2). Somehow even darker is a piece from the very end of the artist’s life, showing not grand institutional cruelty and idiocy, but simply a Fight to the Death between Two Stout Men: one, looking directly towards the viewer, has pinned the other down and is tilting his head to cut his throat; both of them, like mad children, bear vast grins.

Fight to the Death between Two Stout Men (1824–28), Francisco de Goya. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The great achievement of this show is in the monumental effort of assembling so many of Goya’s drawings in one space; but almost inevitably with so much on display it becomes easy to lose the thread. In certain respects this is all to the good: in keeping with Goya’s tendency to something like graphomania, the most revelatory moments come courtesy of the chance to see whole series in their original sequence. With ‘Sketchbook C’ presented in its entirety, the Inquisition drawings gain a strange gravity not just from appearing together, but from appearing as part of a larger sequence still. Almost a visual diary, the sketchbook places them alongside both more quotidian images of beggars and street life and a striking set of ‘burlesque visions’ drawn in a single evening. For Goya, the normal, the terrible, and the fantastical existed cheek by jowl.

In other respects, however, despite the efforts of curators José Manuel Matilla and Manuela Mena to provide topical and biographical footholds, it is simply too much to take in. And while the beautifully designed catalogue provides useful material, what never quite emerges is a sense of the place and purpose of the ‘private albums’ in Goya’s life. Leaving the show, it is easy to feel a little like the aged figure in the final image, I Am Still Learning (1824–28): inching forwards out of pencilled darkness, feeling that there is still too much to learn.

I Am Still Learning (1824–28), Francisco de Goya. Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

‘Goya Drawings: “Only My Strength of Will Remains”’ is at the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, until 16 February.

From the February 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?