From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

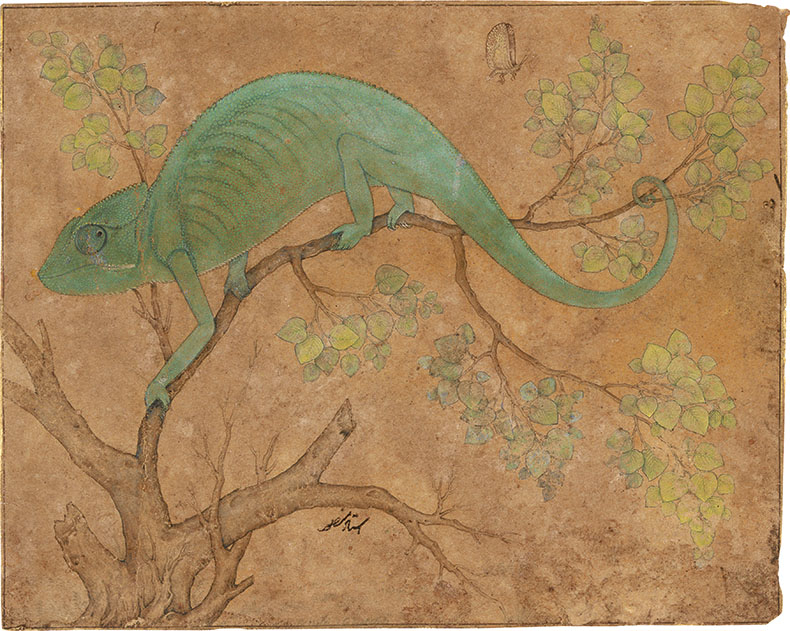

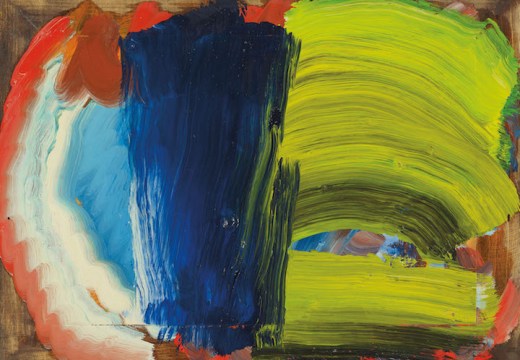

Howard Hodgkin was an unhappy schoolboy at Eton in the 1940s when he was introduced to Indian court painting by his art teacher, Wilfrid Blunt. Better known as an authority on botanical illustration – a genre in which Hodgkin’s mother worked – Blunt also owned some Indian paintings, and he was able to borrow further examples from the royal collection at Windsor Castle to mount an exhibition at the school. Among these pictures was one of a chameleon painted in around 1612 by Mansur, who was employed at the court of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. Hodgkin, who died in 2017, later described it as ‘one of the most extraordinary of all paintings from the Mughal dynasty’. It ignited his passion for this period of art. Although Indian court paintings were comparatively inexpensive at the time, a 14-year-old’s pocket money did not quite stretch that far and so Hodgkin put money on a horse, which lost the race. Undaunted, he managed to scrape up enough cash from other sources to buy ‘a hybrid, seventeenth-century Indo-Persian picture from Aurangabad’. It was, he recalled, ‘very brightly coloured, very pretty, of people sitting around in a garden, drinking wine and lolling about in fanciful positions. It was not a very good picture, but I suppose a reasonably respectable picture for a beginner.’

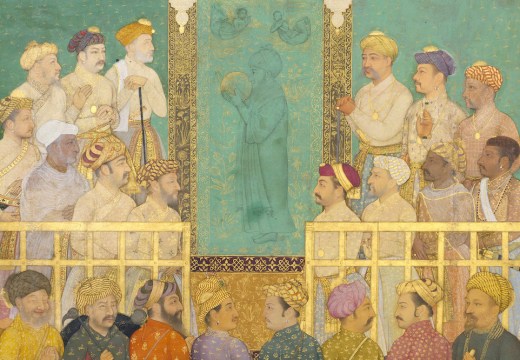

In order to learn more about these paintings, he introduced himself to Robert Skelton, a curator in the Indian department of the V&A, who in turn introduced him to the American scholar – and rapacious collector – of Indian art Stuart Cary Welch, who became a lifelong friend and salesroom rival. (Hodgkin would often tell the story of how Welch tried to put him off bidding on a rare Rajasthani painting – ‘It’s not good enough for you’ – and, having failed to do so, physically restrained him from raising his hand at the auction so that he could buy the picture for himself.) Skelton also arranged introductions to other curators, collectors and dealers when he accompanied Hodgkin on his first trip to India in 1964. Over the next 60 years Hodgkin refined his taste, buying and selling, selecting and discarding, until he had amassed one of the world’s most remarkable collections of paintings and drawings from the Mughal period. Last seen at the Ashmolean Museum in 2012, these are now being put on show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which acquired 84 of them in 2022, five years after the painter’s death, and has borrowed the remaining 38 from the Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust.

Mihrdukht Aims Her Arrow at the Ring (c. 1570), Basawan and Jagan. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

‘My collection has nothing to do with art history,’ Hodgkin once said, ‘it is entirely to do with the arbitrary inclinations of one person.’ Early on Welch had advised him that if you did not get what he called an ‘art zap’ from a painting, you should not buy it. Thereafter Hodgkin never bought anything that did not deliver ‘a shock to the heart’. Whether or not a painting was ‘important’ or usefully plugged a gap in his collection counted for nothing beside his personal, emotional response to it. This is not to say that the collection contains no ‘important’ paintings in the art-historical sense. Works from the principal schools of the period – Mughal, Deccani, Rajput and Pahari – are all, if unevenly, represented. The earliest pictures date from around 1570, during the reign of Akbar, the third Mughal emperor; among the latest is an unfinished and melancholy portrait of the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, who was deposed and exiled by the British after the Indian Rebellion of 1857. In addition to paintings of figures in processions, battles and bazaars, attending durbars, hunting and hawking, pursuing romance, consulting holy men, smoking hookahs, or simply watching the world go by, the collection includes botanical paintings, illustrations of literary texts, Ragamala paintings (depicting the essential qualities of Indian musical ragas), pictures of Hindu gods, and images of birds, animals and gardens. There are also portraits in several markedly different styles, from a sensitive Mughal one of the courtier Iltifat Khan (c. 1640), which is reminiscent of Holbein’s portrait drawings, to a highly stylised, one-dimensional one of Maharaja Suraj Mal with his hawk (c. 1730–40). The collection is in fact all the better for being eclectic rather than doggedly comprehensive.

By the mid 16th century Mughal rule had been firmly established in India and Akbar proved to be one of the most enlightened emperors of the dynasty established by his grandfather 30 years earlier. He promoted intermarriage with the Hindu Rajputs, encouraged contact with Europeans and took a genuine interest in Indian mythology, commissioning translations into Persian of such principal Hindu texts as the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the Harivamsa. One of the most beautiful paintings in Hodgkin’s collection, Krishna Dances On the Head of Kaliya (1590–95), is an illustration for the last of these books, portraying the blue-skinned and yellow-robed god playing his flute as he prances on the many heads of the gigantic serpent king, who is rearing up from the River Yamuna. A picture Hodgkin thought one of the best in his collection, Mihrdukht Aims Her Arrow at the Ring (c. 1570), is also a book illustration from the reign of Akbar, this one of an Islamic text, the Hamzanama, recounting the exploits of the Prophet Muhammad’s warrior uncle Amir Hamza. Hodgkin claimed he had to sell some 60 other Indian paintings in order to buy this one in 1963, but he regarded the Hamzanama as ‘perhaps the greatest single achievement of Indian pictorial art apart from the Ajanta Caves’. Only around ten per cent of the original 1,400 folios survive, and Hodgkin acquired three of them.

Two Orioles (c. 1610), unknown artist, Mughal, India. Howard Hodgkin Indian Collection Trust

Akbar’s son and successor Jahangir was keenly interested in the flora and fauna of his empire and commissioned Mansur and other artists to make many paintings of indigenous animals, birds and plants. A painting of Two Orioles by an unknown artist (c. 1610) depicts two distinct species of the bird artfully arranged and surrounded by flowers as they converge on an insect. It is at once decorative and scientifically accurate, something that would characterise many of the floral decorations of the Taj Mahal, constructed by Jahangir’s son Shah Jahan and the collection includes some exquisite flower paintings and drawings from the latter’s reign.

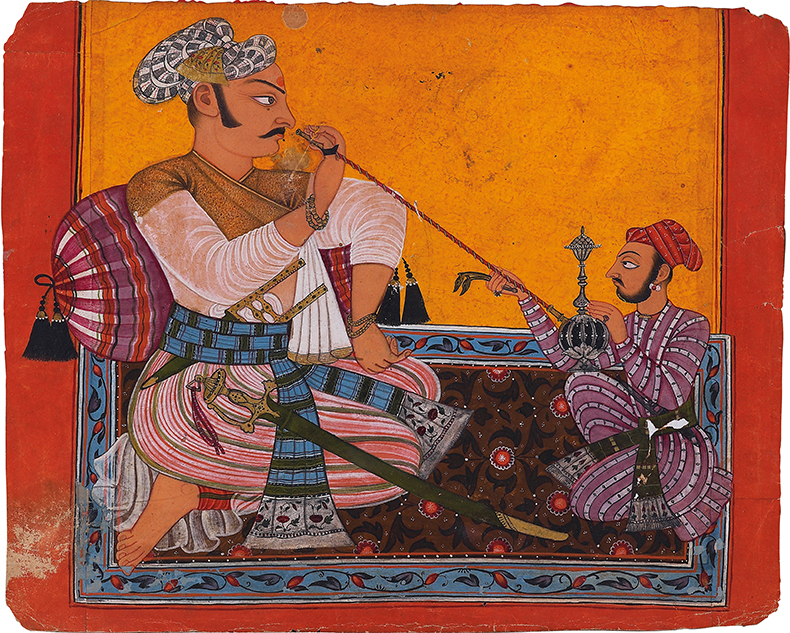

Jahangir determined to keep only the very best artists at his court, and so others departed and helped spread Mughal aesthetic ideas to other regions. This influence was absorbed and adapted by those working at the Deccani, Rajput and Pahari courts. The Deccan sultanates were five kingdoms on the subcontinent’s central Deccan Plateau, and the artists there embraced a style that was considered more ‘poetic’ than that of the Mughal court painters, a quality partly attributed to a more subdued use of colour. This is neatly illustrated by a composite album page in the collection from the mid 17th century in which two brightly hued, full-length royal portraits by Mughal artists are juxtaposed with a painting of a family of elephants by a Deccani one, where the action is lively but the palette is more restrained. By contrast, works by the Pahari (‘Hill’) artists of the 18th and 19th centuries often feature slabs of bold reds and yellows and flattened planes, very different from the Mughal painters’ emphasis on perspective and realism. This is particularly characteristic of the Ragamala paintings, of which there are several example in the collection, but is also true of depictions of real people. Maharaja Bhupat Pal of Basohli Smoking (c. 1685), for example, though charming, seems almost cartoonish compared with Mughal paintings of similar subjects, such as Nobleman Smoking on a Terrace (c. 1670). This should, however, be regarded simply as a different aesthetic, and two paintings in the collection featuring episodes from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, attributed to Manaku and Nainsukh, brothers working at the Pahari court of Guler in the 18th century, not only seem nearer the Mughal style, exemplifying the cultural exchange between different schools, but are highly original and sophisticated narrative works in their own right.

Maharaja Bhupat Pal of Basohli Smoking (c. 1685), Mankot. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

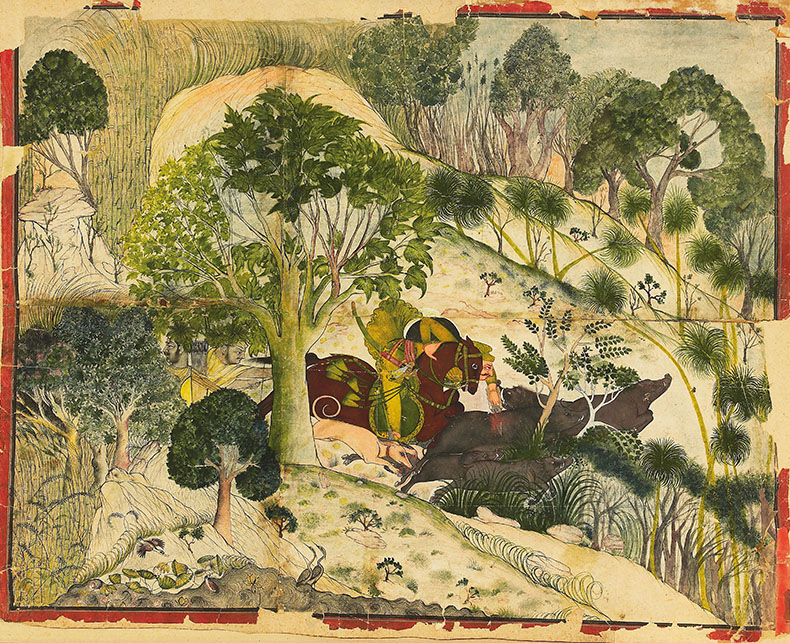

Rajput court painters were expected to record and celebrate the lives of their patrons, even following them on to the hunting field or into battle. One task was to produce heroic images of their rulers’ exploits, as in Maharao Madho Singh Hunting Wild Boar (c. 1720) – though this is in fact an imaginary depiction of this extremely dangerous sport, painted some 70 years after Madho Singh’s death. A very different approach is taken to the highly cultivated Maharaja Raj Singh of Sawar, who is twice portrayed at leisure in his garden. The first picture, Maharaja Raj Singh in a Garden Arcade (c. 1710–15), is a formal portrait in which he is depicted with the flat profile favoured by Rajput artists, resting his arm on a carpeted balcony and holding a flower in his right hand. Unlike European portraiture, where a flower held in this manner usually denotes an impending marriage, in Indian painting it symbolises the sitter’s sensibility and connoisseurship. The modelling of his face and costume is far less lifelike than that of earlier Mughal portraiture. This more representational approach is equally apparent in Maharaja Raj Singh Receives a Yogi in His Garden (1714), the flattened perspective of which, along with its grid pattern and red border, give it the appearance of a board game. In the upper half of the painting the maharaja and the yogi smoke hookahs, with standing and sitting attendants to left and right. A row of highly stylised flowers (with peacocks) separate them from a formal garden, in which 12 compartments contain plants, birds and a cypress-flanked fountain, while another two contain further attendants. Running along the bottom of the composition, like a predella, are symmetrically arranged groups of four musicians separated from a pair of fighting elephants by two palm trees. While the parchment-coloured background and subdued palette may be similar, this painting is otherwise very different from the contemporaneous and highly animated Maharajah Raj Singh and His Elephants (c. 1710–15) depicting the ruler on a hawking expedition in the hills, sitting in a howdah and surrounded by 13 other elephants, all going full tilt.

Maharao Madho Singh Hunting Wild Boar (c. 1720), attributed to Kota Master A. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

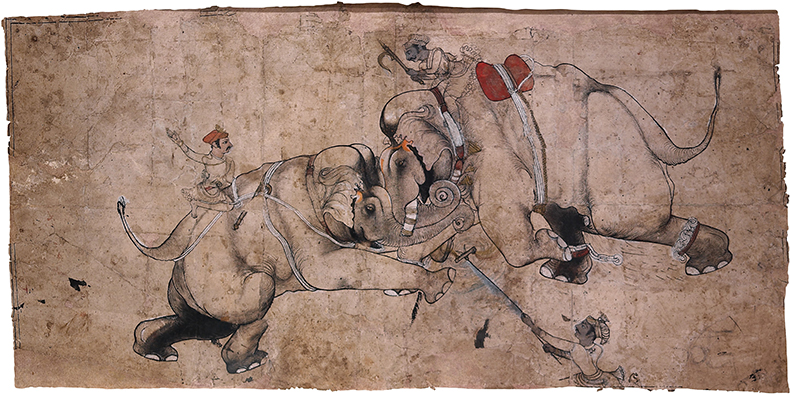

Paintings of elephants, particularly those of the Rajasthani Kota school, became something of an obsession for Hodgkin. He even broke his self-imposed rule by buying ones executed well after his supposed collecting cut-off date of 1857, though these were disposed of in the Sotheby’s sale of his possessions in 2017. The best of his elephant pictures, from all schools and periods, are gathered into one room for the exhibition, and they are indeed irresistible. One of the earliest paintings in the collection is A Prince Riding an Elephant in Procession (c. 1570), a crowded fragment from a larger work on cloth painted for Akbar when he moved his court to Fatehpur Sikri. The prince in question, whose figure has been rendered featureless by paint loss, may well be Akbar himself, since he was an enthusiastic and skilled mahout, and the procession includes six other richly caparisoned adult elephants and a baby one trotting along beside them with a very determined look in its eye.

Elephant Fight (c. 1655–60), attributed to Kota Master. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Elephants played such an important role in Mughal life that individual portraits were made of them, sometimes inscribed with their names: Khushi Khan (‘Lord of Happiness’) or Firuz Jang (‘Victorious in War’; see cover). These beautifully delineated pachyderms, mostly from the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan, fill the whole picture plane. Sultan Muhummad Adil Shah and Ikhlas Khan Riding an Elephant, painted in the Deccan in around 1645, is similar in style and composition, but other Deccani and Koti paintings of elephants tend to depict them less formally, often in dramatic action. In Elephant Trampling a Horse (mid 17th century), the subjects, painted in opaque watercolour on marbled paper, tumble together in a confusion of limbs, while in Elephant Fight (c. 1655–60) two pachyderms seem to have charged on to the paper from either side to clash heads in the middle.

Hodgkin always insisted that the pictures he collected had no influence on those he painted, even those he painted in India. Buying these works, however, became as much a part of his life as making art, pursued with the same attention and dedication. This may be one individual’s personal collection, but as Hodgkin once said, seen together they are not only ‘great art’ but incidentally portray ‘life as lived in India between 1570 and the mid 19th century’.

Chameleon (c. 1612), Mansur. Royal Collection Trust. Photo: Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III 2023

‘Indian Skies: The Howard Hodgkin Collection of Indian Court Painting’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from 6 February–9 June.

From the February 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?