It is a truth universally acknowledged that statues of public figures are hated by everyone, except perhaps their creators and, hopefully, their subjects, if they’re still alive to see them. Jane Austen will of course not be around when, or if, the statue commemorating her 250th birthday is erected at Winchester Cathedral next year, but according to Winchester resident and Jane Austen Society vice president Elizabeth Proudman, the author would not have approved of the proposal anyway. ‘She is known to have been a modest woman who shunned publicity,’ Proudman wrote in a letter to the Hampshire Chronicle in December.

Similar views were aired at a public meeting last week, in which local residents raised concerns that an Austen statue would lead to the ‘Disneyfication’ of the cathedral. Proudman herself is quoted as saying, ‘I don’t think we want to turn it into Disneyland-on-Itchen’. Having seen images of the statue’s maquette – admittedly, not the finished product – Rakewell feels compelled to observe that this seems unlikely. It is no disrespect to the statue’s creator, Martin Jennings – who has such works as the coin effigy of King Charles III and the John Betjeman statue at St Pancras station to his name – to say that it’s difficult to imagine hordes of parents being woken up on the first day of the summer holidays by their screaming six-year-olds begging to be driven down the A31 to catch a glimpse of Austen in the bronze.

Maquette of Jane Austen statue by Martin Jennings. Courtesy the artist/Steve Russell Studios

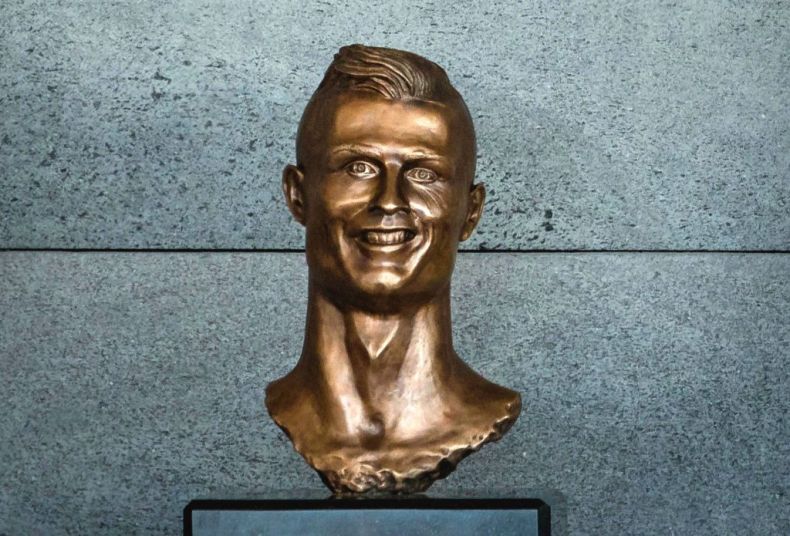

Winchester’s is not the first wrangling over a sculptura non grata in recent years: Maggi Hambling’s much-derided attempt to capture the ‘spirit’ of Mary Wollstonecraft on Newington Green, for instance, which revealed that the ‘spirit’ of the greatest feminist thinker of the 18th century was in fact a tiny nude woman surfing a misshapen version of one of those massive subterranean worms from Dune. Or the eminently meme-able bust of footballing GOAT Cristiano Ronaldo that was unveiled at Madeira airport in 2017, which some commentators observed looked more like the former F1 star David Coulthard. To his credit, the bust’s creator, Emanuel Santos, defended himself admirably from the backlash, telling an interviewer, ‘Even Jesus did not please everyone.’ Preach, Emanuel.

Cristiano Ronaldo, as seen by Emanuel Santos

Bad likenesses have a long and storied lineage. When Auguste Rodin’s ogreish Monument to Balzac went on display in Paris 1898, it caused such distaste that it was rejected by the Société des Gens de Lettres, the very group that had commissioned it in the first place. Yet by 1969 Kenneth Clark had declared it ‘the greatest piece of sculpture of the 19th century’; wander among the hedgerows of the Musée Rodin’s gardens today and you’ll stumble upon it in pride of place. Perhaps there’s a lesson in that for Jennings, Hambling, Santos and all the other maligned craftspeople around the world: just wait 70 odd years and things will blow over. By the year 2095, perhaps Austen, Wollstonecraft and Ronaldo will be standing toe to toe, gracing the gardens of some prestigious, as-yet unbuilt gallery. Or, as Lady Russell wisely remarks in Persuasion, ‘time will explain.’

Hambling’s sculpture For Mary Wollstonecraft (2020), installed on Newington Green, London, in 2020. Photo: Ioana Marinescu

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?