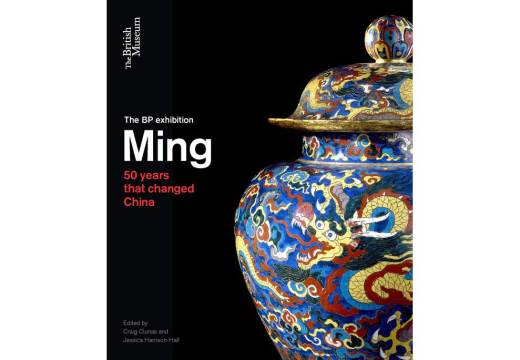

Reading the title of this exhibition you could be forgiven for thinking that the Ming dynasty lasted for 50 years. In fact it lasted for 276 (1368–1644) and the exhibition focuses on 1400–1450, a period in which Beijing was established as the capital and China experienced a ‘golden age’ of prosperity and artistic creation. The first thing that comes to mind at the mention of ‘Ming’ is blue and white porcelain; but the artistic creations of this flourishing early period were far more diverse.

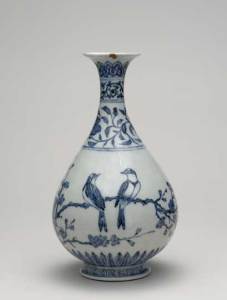

Porcelain bottle with underglaze cobalt blue decoration (Yongle era, 1403–1424), Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province © The Trustees of the British Museum

Thanks to loans from over 30 institutions with many of the exhibits on view outside China for the first time, the curators have been able to make use of the full vocabulary of the early Ming arts to express the cosmopolitan, multi-faith and international nature of China at this time. Certain parallels with some of the issues facing us today are no doubt intentional.

Enter our book competition before 10 October for a chance to win the exhibition catalogue.

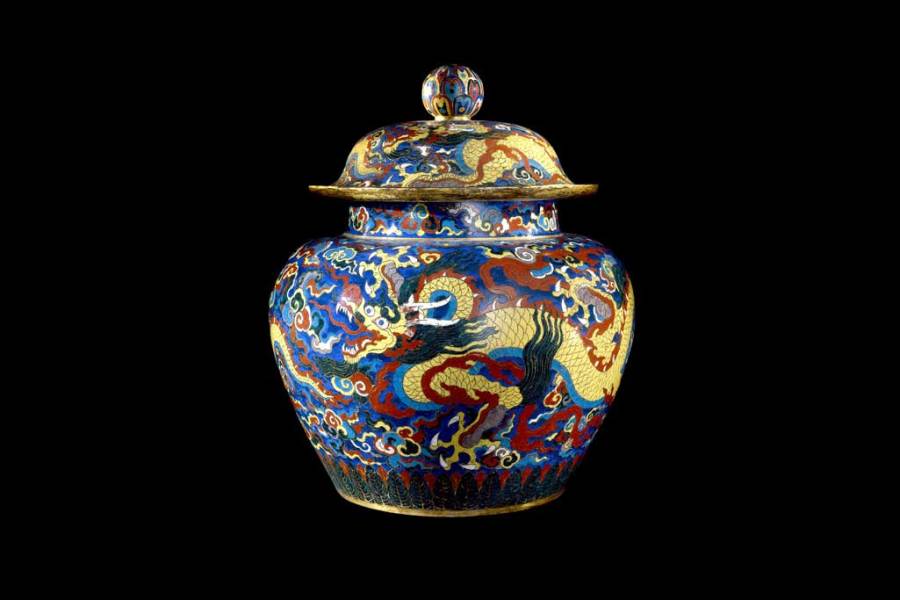

The exhibition is divided into sections addressing courts, war, peace, beliefs and commerce, and attempts to demystify early Ming China by placing emphasis on its cultural interactions. The most familiar and readily appreciated exhibits will be precisely those that have been traded for centuries: fantastic works of art in gold, silver, lacquer, jade, textiles and of course ceramics. A rare treat is to see blue and white porcelain alongside the metal and glass objects from the Middle East that inspired their shapes. Don’t miss the original Ming hats, which can subsequently be spotted throughout the exhibition in paintings or carved into lacquer dishes. For sheer virtuosity, the Xuande carved red lacquer table (usually housed at the V&A) and Lady Wei’s gold filigree phoenix hairpins can have few rivals.

Painting and calligraphy are considered to be at the pinnacle of the artistic hierarchy in China, and their status largely kept them out of circulation as trade goods. Here they reflect the Chinese culture of the period and the extension of literacy through printed books. The ‘Amusements in the Xuande Emperor’s Palace’ scroll features many sports that we still enjoy today. In the ‘Beliefs’ section, the coexistence of multiple faiths in China is addressed through a full range of religious arts including a stunning silk embroidered Thang ka and a near life-sized Xuande gilded bronze standing figure of Buddha.

‘Amusements in the Xuande emperor’s palace’ (detail showing the emperor playing an arrow-throwing game; Xuande period, 1426–1435), Anonymous © The Palace Museum

The final exhibit is a painting by Mantegna of the Adoration of the Magi, in which the gold is presented to the Christ child in a blue and white porcelain cup. Next to it is just such a cup. Judged by the Chinese as fit for emperors and by their contemporaries in Europe as fit for gods, it is perhaps not surprising that it is porcelain that remains the lasting legacy of the Ming dynasty to this day.

‘Ming: 50 years that changed China’ is at the British Museum, London, until 5 January 2015.

Enter our book competition before 10 October for a chance to win the exhibition catalogue.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?