From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Cinema is a collaborative art, and auteurist accounts that centre the director’s vision often seem at odds with the actual process of film-making. But Stanley Kubrick was a special case; a director who won an astonishing degree of autonomy from the Hollywood studios that financed his films and used it to control almost every aspect of those films: the scripts, the performances, the lighting and camerawork, the mise en scène down to the smallest details of sets and props, the gradations of colour in the prints, how the films were promoted and, later, even the typefaces on the boxes of VHS and DVD releases. Over a period of almost 50 years, he made only 13 features and garnered few of the conventional badges of esteem – Oscars, Palmes and whatnot – but it is hard to think of another great director whose films range more widely across genre and theme, or who is as revered by his peers (Sight and Sound’s decennial poll of directors at the end of 2022 put 2001: A Space Odyssey in first place).

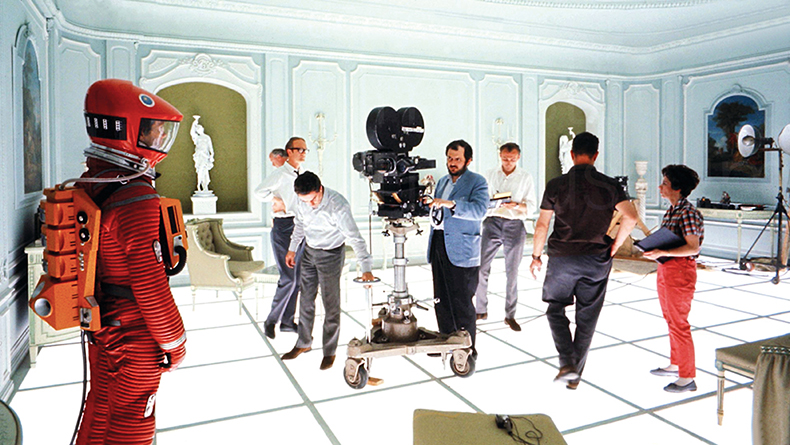

Stanley Kubrick with cast and crew on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Courtesy Collection Christophel © Metro Goldwyn Mayer

Reverence is not necessarily a good basis for biography, and Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams, both scholars of film, do at times succumb to it. They aren’t stylish writers, either, and I winced at some of the under-edited sentences in this book – surprisingly, the first big life of Kubrick since he died. But it would be quite an achievement to make such a restlessly intelligent, energetic, perfectionist and eccentric character dull. He was born in 1928 in Manhattan, into a Jewish family (the book returns to Kubrick’s Jewishness repeatedly, not always usefully), and grew up in the Bronx. He did not excel academically and left school at 17, but he had already begun to take photography seriously as a hobby, and within a few months was the youngest photographer on the staff of Look magazine, being sent on assignments that showed him aspects of life few of his contemporaries would see, and learning about lenses, lighting and exposures. Later, directors of photography on his films attested to his extraordinary technical knowhow, which in one or two cases left them feeling sidelined and resentful. And though he was celebrated for the fluid mobility of his camerawork, his awareness of the still image is always clear – in the echoes of Reynolds, Gainsborough, Hogarth and Joseph Wright in Barry Lyndon (1975), for example, and in the allusion to Diane Arbus in the weird twins of The Shining (1980).

At Look, he was already thinking about moving pictures; at 21 he started a low-budget film company with a school friend, producing documentaries. At 23 he made a clumsy, pretentious war movie, Fear and Desire (1952), which he later disowned; Killer’s Kiss (1955) was a noirish love story, again tainted by pretension but showing imagination and visual flair. He couldn’t have completed either film had he not already developed a knack for persuading people to work for deferred payment or none at all, on the grounds that working with him was worth more than money. Later on, wealth and fame enabled him to refine this technique. Michael Herr, who worked with him on the screenplay for Full Metal Jacket (1987), described Kubrick’s attempt to get him to do a ‘wash and a rinse’ on the script for his final film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999). He wanted it to be a personal transaction, without reference to Herr’s agent, ‘for a complex of reasons involving money and secrecy, affection and control, respect and pathology and old times’ sake’.

Charles McGraw, Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas during the filming of Spartacus (1960).

The early years do not always make for an easy read, partly because the young Kubrick’s ruthlessness and ego make him hard to warm to. But the pace picks up, and Kubrick softens and becomes a more intriguing protagonist as his career progresses through his first really accomplished feature, the complex, bleak heist story The Killing (1956), and his first brush with stardom: the bitter First World War drama Paths of Glory, starring Kirk Douglas (1957). That film also introduced him to his wife (his third, after two short-lived early marriages), Christiane Harlan, who seems to have given him a level of domestic security that allowed him to flourish. There followed the commercial triumph of Spartacus (1960), which fixed his determination to stay apart from the Hollywood studios; hence the move to England for the uneasy comedies Lolita (1962) and Dr. Strangelove (1964). The woozy cosmic vision of 2001 (1968) and the porno violence of A Clockwork Orange (1971), each chiming with the zeitgeist in unpredictable ways, gave Kubrick the clout to do almost whatever he wanted.

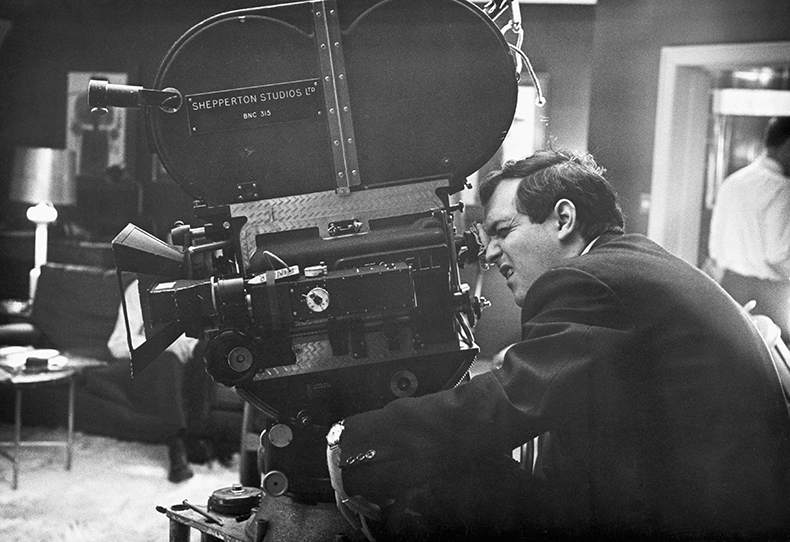

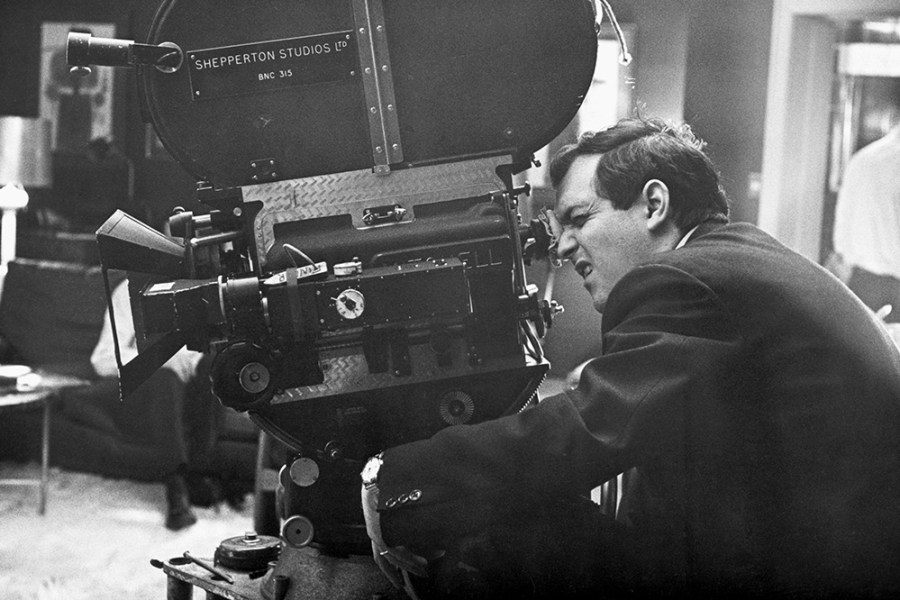

Stanley Kubrick filming Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (detail; 1964). Photo: George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

It is somewhere around this point that the book becomes really absorbing, as Kubrick uses his freedom to become more completely himself – obsessive, neurotic, totally engrossed in his work, his wife and daughters and his vast numbers of cats and dogs. At times, he could be horrifyingly oblivious to the feelings of colleagues and employees – the demands he made on the production designer Ken Adam while making Barry Lyndon drove Adam to a breakdown. Writers whose books he adapted, or whom he brought on board to help with scripts, were regularly outraged at the liberties taken with their work. But, as at the start of his career, many of those most harshly exploited were persuaded that it was all worth it for the experience of working with him and for the quality of the final result; Adam remained friends with him, though he said that he knew they would never work together again. (It should be said, though, that some did simply feel abused, and Kolker and Nathan are too ready to exculpate their subject.) The projects he failed to make – a Napoleon film, a Holocaust film, an adaptation of a 1960s BBC radio sci-fi serial – loom almost as large as the ones he did: Barry Lyndon – to me his greatest film, for its ravishing images and the perfect imitation of Thackeray’s voice in Kubrick’s script – The Shining, Full Metal Jacket and, after an almighty gap, Eyes Wide Shut, the fruit of a decades-long ambition to film Arthur Schnitzler’s novella Dream Story (1926). He died weeks before that film was released, 25 years ago, at the age of 70. It is dismaying to imagine what he might yet have produced.

Kubrick: An Odyssey by Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams is published by Faber.

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam still got the hang of things?