Today we can’t help but see the Weimar Republic in terms of its tragic denouement: the rise of Hitler and all that followed. But for those living there, the present was already insecure, often brutal, and as the historian Eric Hobsbawm would later recall, ‘unbelievably exciting, sophisticated, intellectually and politically explosive’. And it demanded new forms of expression.

These included, most famously, the plays of Bertolt Brecht, German Expressionist film, Dada, cabaret, and Marlene Dietrich. But there was another tendency that emerged at this moment, just as revolutionary in its way. It was known loosely as the Neue Sachlichkeit, meaning ‘New Objectivity’ or ‘New Sobriety’. Artists under its sway aimed to understand their time through its people – staring the zeitgeist right in the face, as it were. And, as an impressive exhibition at Tate Liverpool shows, they’ve left us with a remarkable window on to the era too.

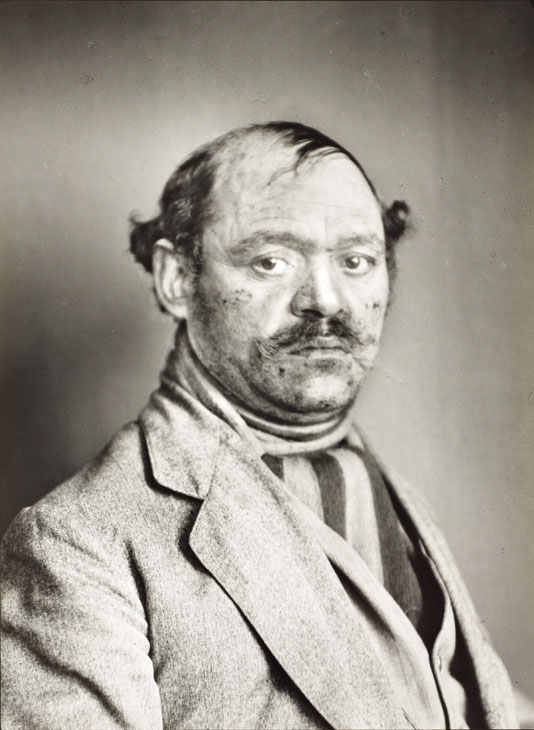

Turkish Mousetrap Salesman (1924–30), August Sander. © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; DACS, London, 2017

‘Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919–1933’ tells the story of the Weimar Republic through the work of just two artists: the photographer August Sander, and the painter and printmaker Otto Dix. It’s a fantastic one-two punch. Though very different in both medium and temperament, they shared a determination to seek out and represent every recess of German society, and thereby to expose some deeper truth.

The first half of the show is devoted to Sander’s astonishing photographic project, ‘People of the Twentieth Century’. Over four decades, Sander set out to document and classify the entire social structure, accumulating thousands of images. 140 of them are on show here. In stark focus, surrounded by the paraphernalia of their daily lives, the subjects gaze passively from the centre of each portrait. They have no names, only labels placing them in Sander’s taxonomy of ‘archetypes’. Descriptors such as ‘Village Schoolteacher’, ‘Working Class Mother’, and ‘Beggar’ are assigned to the categories ‘Classes and Professions’, ‘The Woman’, and ‘The Last People.’

National Socialist, Head of Department of Culture (c. 1938; printed 1990), August Sander. © Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; DACS, London, 2017

Running alongside these photographs, which wind around three rooms, the curators have supplied a timeline of Weimar Germany. You suspect Sander would have approved, since this adds to the impression of mere individuals lost in the maelstrom of history. It’s doubtful, however, that this sangfroid brought the photographer any comfort when that history bore down on him. In 1933 his son Erich, a Communist, was sent to prison, where he would eventually die. At this point Sander’s portraits begin to feel despairingly muted, as they receive labels like ‘National Socialist’ and ‘Victim of Persecution’.

This brings us to the second half of the show: the paintings, drawings and etchings of Otto Dix. If Sander has given us all the background we could ask for, Dix now gives us the foreground, in vivid and often disturbing detail. His was a different sort of ‘objectivity’, an amoral fascination with the beauty and potential of a society in tumult. His mission, most stunningly expressed in his lurid, crystalline style of portraiture, was ‘to expose ugliness and life undiluted’.

Reclining Woman on a Leopard Skin (1927), Otto Dix. © DACS 2017. Collection of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University.

As Susanne Meyer-Büser points out in the exhibition catalogue, Dix returned from the First World War as a man on the make and no doubt ambition played a part in his self-styling as ‘proletarian rebel and big-city dandy.’ At any rate, he soon made a name for himself as a nihilistic observer of the demi-monde, as shown by the titles of some etchings Dix sent to an art dealer in 1920: War Cripples, Match Dealer, Sex Murderer, Lady in the Café, Card Players, and Butcher Shop.

In the following years, this cast grew to include bourgeois patrons, intellectuals, and performers, as Dix began churning out his dazzling portraits. He was profoundly inspired by the Old Masters, reviving both their compositional style and painting techniques. This meant placing his subjects proudly in the front and centre of the picture plane, giving them a confrontational air. It also led to his method of ‘glazing,’ a practice involving layers of thin oil paint and tempera, which produced unparalleled lustre and immediacy.

Self-Portrait with Easel (1926), Otto Dix. © DACS 2017. Leopold-Hoesch-Museum & Papiermuseum Düren. Photo: Peter Hinschläger

This visual splendour, however, was always for Dix a means of gazing into the souls of his subjects. Whether capturing the woollen texture of a suit in his Portrait of the Photographer Hugo Erfurt with Dog (1926), or rendering, with a painfully delicate brush, each pubic hair of his Nude Girl on a Fur (1932), his paintings show a flair for characterisation that any novelist could admire.

It’s possible to see Sander and Dix as the yin and yang of European modernism in this period. Sander sought to understand the world by imposing order, Dix by flirting with chaos. Both remind us of an actor who we tend to forget is on the stage during these frantic episodes in history: the detached observer, committed only to showing things as they are. I should add that, with over 300 works and many metres of wall text, this exhibition is heavy going. But rarely will you see a period of turmoil and flux brought to life with such depth and lucidity.

‘Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919–33’ is at Tate Liverpool from 23 June–15 October.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Are the art market’s problems being blown out of proportion?