One legend about Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652) recounts that the first owner of his Ixion (1632) had to dispose of the painting as if it were a cursed object. Lucas van Uffel’s wife, Jacopa, had been so shocked by the depiction of Ixion’s fingers contorted with agony that she gave birth to a child with deformed fingers. Joachim von Sandrart, the recorder of the anecdote, does not mention whether or not the van Uffels saw fit to warn the new owners of the possible risks they were running, but the moral is clear: Ribera’s art represented suffering so strikingly that it could reach out beyond the frame and into the bodies of viewers.

Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women (c. 1620–23), Jusepe de Ribera. Photo: courtesy Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao; © Bilboko Arte Ederren

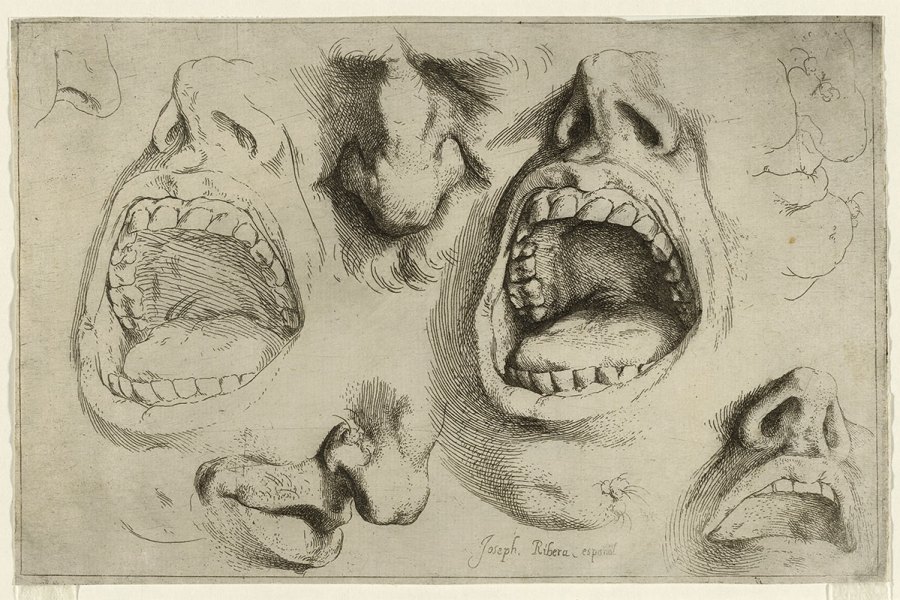

Ixion and its companion pieces from the Furias series are not on display at the Dulwich Picture Gallery’s excellent ‘Ribera: Art of Violence’, but the notion that pictorial violence is rarely solely pictorial is central to the show. Curators Xavier Bray and Edward Payne home in on the permeability of the barriers between mythology, religious history, art and the lifeworld of the artist and his audience. Two versions of the flaying of Saint Bartholomew (1628, 1644) and one of the flaying of Marsyas (1637) are set alongside the famous écorché designed by Gaspar Becerra for Juan Valverde de Hamusco’s anatomical treatise of 1556, Historia de la composición del cuerpo humano, which in turn stands beneath a scrap of preserved human skin from the 19th century, carefully tattooed with a grim reaper and a grave. This leads on to The Sense of Touch from Ribera’s series on the five senses – reminding the viewer that skin is as much a site of lived experience as of grisly death.

There is a clear connection between Ribera’s fascination with human bodies bound and stressed and the innumerable places in early modern Europe where such things were an everyday occurrence. In his art, the bound form seemingly verges on an obsession for Ribera: along with the tied and flayed Marsyas and Bartholomew, there is the stiller, more tender Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women (c. 1620–23), here surrounded by an array of sketches and studies on similar themes. Along with an exquisite Crucifixion of Saint Peter (mid 1620s) in red ink and chalk, there is figure after figure stretching or slumping in their bonds against an all too rigid support. Turn to one side in the gallery, and the same shape can be made out in two of the prints from Jacques Callot’s Les misères et les malheurs de la guerre (1633): one of a man bound to a stake for the firing squad, the other of a man being burned alive. Such endings were not the exclusive province of martyrs, distant in early Christian history; they were part of everyday early modern justice at its most cruel. Ribera, with his characteristic eye for detail, homes in on the victim at the expense of surroundings or reasons for punishment: in one drawing from the 1640s on display here, he has carefully marked not just the links of a chain around the victim’s waist but the painful stretch of his neck straining at a cord around his throat.

Man Bound to a Stake (first half of the 1640s), Jusepe de Ribera. Photo: © Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

The juxtaposition of Ribera and Callot is inspired – and happily undercuts the occasional prurient sense that the exhibition gives of prying into a private sadistic fascination on Ribera’s part. While he clearly felt compelled to return to such scenes time and time again, the show reminds viewers that the gruelling violence of his art was, in some sense, quotidian. Nowhere is this clearer than in his studies of torture by strappado – in which victims were hoisted by a rope tied to their wrists and bound behind their back, until their shoulders slowly dislocated. The strappado appears in Callot too, but it is the crude doodles of it littering the margins of a 1596 record of criminal punishments from Rome displayed here that make clear just how common a practice it was. In an otherwise unremarkable anonymous painting from the mid 1600s, one equally unremarkable victim dangles over a jolly market scene, ignored. The setting is Vicaria in Naples, the city where Ribera spent the bulk of his career. Given that the artist may well have walked through the same scene himself, more than once, the question seems less ‘Why was he so fascinated by torture?’ than, ‘How did other artists ignore it so successfully?’

Apollo and Marsyas (1637), Jusepe de Ribera. Photo: Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte; courtesy the Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo

This is by just about every measure a superb show – not least of all because it is such a coup for the Dulwich Picture Gallery to be able to gather and show works of this quality. The catalogue by Bray and Payne – with extensive commentary on the individual pieces – is a useful companion to a show curated with rare verve and care. It would almost be worth seeing just for Apollo and Marsyas (1637) alone, in which Ribera’s Apollo slowly tears the skin from the satyr’s leg, not with a knife but with his bare hand, all the while wearing the strangely tender expression of a nurse removing a wound dressing. With the other works on display, it is unmissable.

‘Ribera: Art of Violence’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until 27 January 2019.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?