The Romanian-American cartoonist Saul Steinberg represented a distinctly mid 20th-century phenomenon, one so familiar we tend to forget how bizarre it is. He was born in 1914 to second- and third-generation Russian Jewish immigrants in a small town in Romania and grew up in what he later called ‘the Turkish Delight manner’, in a milieu where Ottoman and Western ideas and styles intermingled. After the First World War, however, the Romanian political climate became increasingly informed by anti-Semitic nationalism. Having entered the University of Bucharest to read philosophy, at the age of 19 Steinberg transferred to the Politecnico in Milan to study architecture. Eight years later he was forced into hiding when Fascist Italy, at the behest of its wartime ally Germany, introduced vicious anti-Semitic racial laws. He was arrested and spent a month in a detention camp, fleeing on release to neutral Portugal, and thence to the United States. Denied entry at Ellis Island because he had doctored his passport with a fake stamp in order to board ship at Lisbon, he spent a year in the Dominican Republic waiting for a genuine US visa. It was during this time that his work started to appear in the New Yorker, which helped expedite his visa application.

Steinberg’s most famous image is a New Yorker cover from 1976: ‘View of the World from 9th Avenue’, a vision of the rest of America – and of the world, for that matter – as an insignificant outskirt of Manhattan, just across the Hudson. It has been described both as the greatest magazine cover of all time and as an unwittingly self-damning vision of Manhattan parochialism, drawn by a man who enjoyed nearly 60 years as a fixture at the New Yorker, the house magazine of Manhattan entitlement. It was parodied so often that Steinberg felt compelled to go to court to assert ownership. He grew to resent the image, fearing it would eclipse everything else he had done.

If it has, that’s a shame. For while Steinberg may have contributed to the creation of a specifically New York brand of refined, achingly cool modernist civilisation – you’ll recognise the Mad Men aesthetic of sleek cocktail shakers, leftists in lofts, streamlining, tiny paper napkins on a table in a darkened room – the entitled parochialism is its least interesting aspect. Far more compelling is the way that it was underpinned by a mash-up of Balkan orientalism, flight, fear and murderous political madness. For decades, Steinberg was lauded for his contribution to this aesthetic, often by the kind of European modernist he had been forced to leave behind. Le Corbusier told him ‘You draw like a king’; he was praised by Ernst Gombrich, Italo Calvino, Eugène Ionesco and Roland Barthes, attaining a cultural superstardom rare for cartoonists. Even more than Ronald Searle and Ralph Steadman, Steinberg closed the gap between what ‘cartooning’ is often assumed to be – cheaply reproduced, silly scribbles knocked out to make you laugh – and ‘art’, which is supposedly so much nobler.

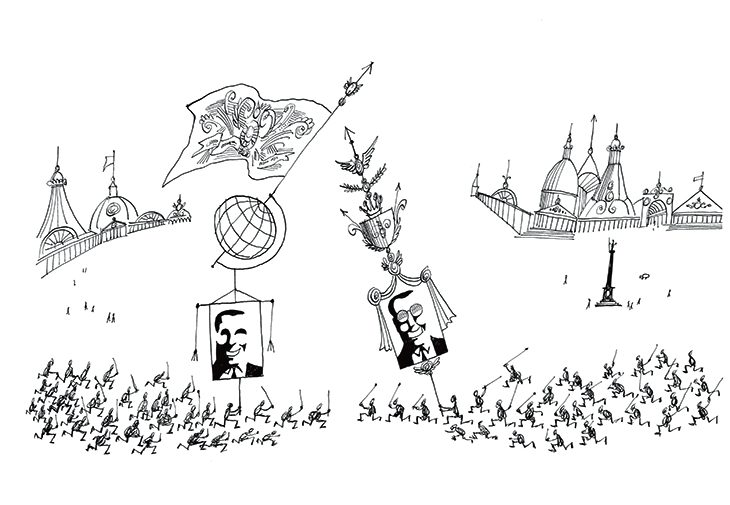

Untitled (Demonstration) (1957–59), Saul Steinberg. © 2018 The Saul Steinberg Foundation

Given this hierarchy, it’s significant that Steinberg described himself as ‘a writer who draws’. Cartoonists work in the no man’s land between text and image – the standard cartoon is a chimera composed of image and caption, the one often undermining the other. Great cartoonists transmute the form into ‘art’ to the extent that they push conventions beyond breaking point. Searle and Steadman did it by consciously fracturing lines and overdrawing, like George Grosz; Steinberg by rendering text as drawing. In his collection The Labyrinth (1960), just reissued by New York Review Books with a new introduction by Nicholson Baker, time and again language becomes simply squiggles, or words are drawn almost architecturally, as edifices dominating landscapes.

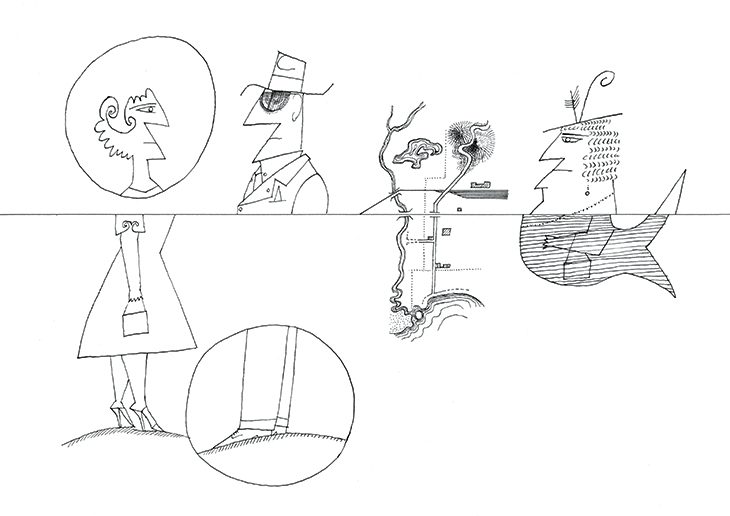

Collecting published and unpublished drawings, and meticulously arranged by Steinberg himself, the book begins with a horizontal line, bisected initially by some geometry, and then providing a platform for one of Steinberg’s trademark ragged crocodiles (he was nearly eaten by a crocodile on a trip to Kenya with Saul Bellow). What we can expect, turning the page, is to not know what on earth we can expect. As a writer who draws, he might be about to wrangle this line into a letter and then into a line of words; or it might become a horizon, the reflecting surface of a lake, a washing line, a collar, the edge of a room, a strand of a labyrinth exploding up and down the page. But then you turn the page to a procession of talking heads, each producing vast, abstract yet baroque speech-bubbles. This is so much more than Paul Klee’s ‘taking a line for a walk’: Steinberg takes it on a forced march, a drunken lurch and a frenzied fandango.

The Line (one of eight sheets; 1959), Saul Steinberg. © 2018 The Saul Steinberg Foundation

Later, a double-page spread riffs on newspaper comic strips, the topography of the frames filled with written and pictorial gibberish. Then there are pages of window frames; sparse, almost agoraphobically enormous vistas of Red Square and other Soviet landmarks; society women scribbled as prim, winged harpies. Then cats, then crocodiles, then random geometric shapes, and more crocodiles. Squiggle landscapes anticipate ‘View of the World from 9th Avenue’; some drawings are exquisite; others are barely drawn at all. On one page he appears to channel Chagall, then Picasso, then – weirdly – the young Nicolas Bentley, then Dalí, then George Herriman (the creator of Krazy Kat). If Steinberg had been a draughtsman who wrote and this were text, I doubt much of it would make sense – any sense at all.

So, was that cavalcade of cultural bigwigs who bigged up Steinberg reading meaning where there was none – or, worse, archly teasing meaning from the very fact of meaninglessness? Again, it doesn’t matter. Steinberg’s art aspires towards the condition of the doodle. Endlessly fleeing the collapse of European cosmopolitanism into barbarism, Steinberg snuck through Ellis Island riddled with the bacilli of the cultural responses to that calamity. Like Ronald Searle, who reshaped the trauma he suffered as a prisoner of the Japanese into the dark hilarity of St Trinian’s, he found redemption through cartoons of baffling, disquieting whimsicality. Both artists deliberately replayed tragedy as farce, less to imbue meaninglessness with meaning than to make it bearable by making it funny. While this book, like Steinberg’s output in general, is as inescapably the product of its time as are the rings in a felled tree, its timeless relevance lies in the rueful smiles it can still conjure.

The Labyrinth by Saul Steinberg is published by New York Review Books.

From the January 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has arts punditry become a perk for politicos?