From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

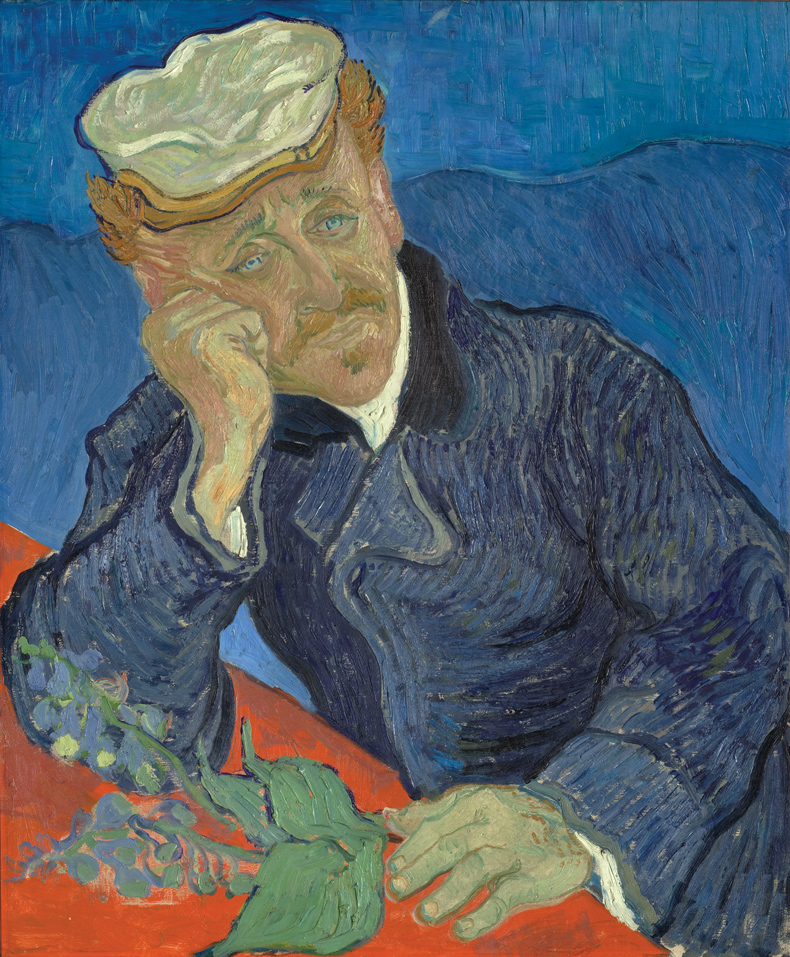

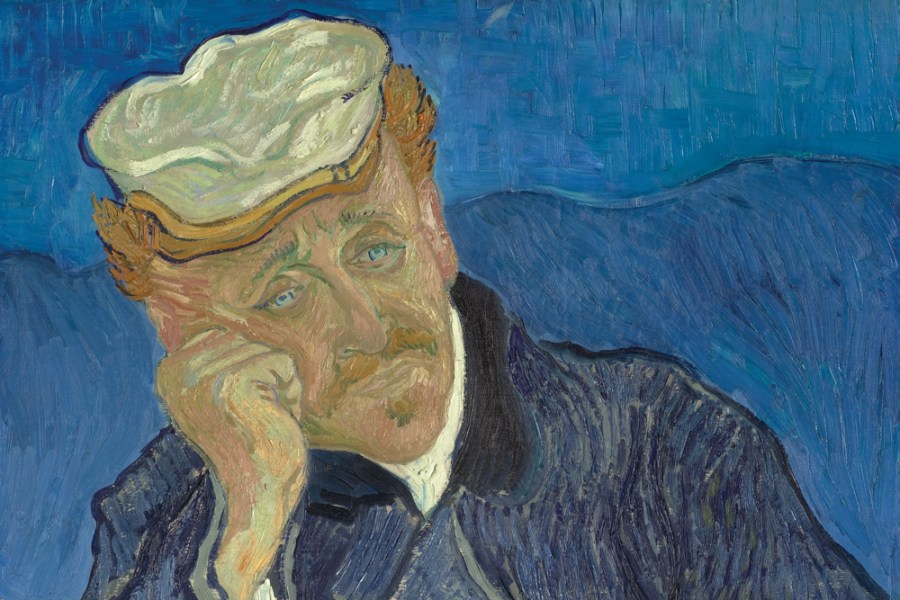

In 1890, Vincent Van Gogh painted a portrait of Dr Paul-Ferdinand Gachet in a brooding pose reminiscent of Dürer’s Melencolia I, his clenched fist to his cheek. A homeopathic doctor, with a furrowed brow and watery gaze, he looks out dolefully over a foxglove, known as ‘opium of the heart’, to indicate his lovesickness. Gachet, his ‘face the colour of an overheated brick, and scorched by the sun, with reddish hair and a white cap’, according to the artist, has ‘the heartbroken expression of our time’. Van Gogh wanted to create modern portraits that used colour to convey heightened emotion: ‘I should like to paint portraits which would appear after a century to the people living then as apparitions,’ he wrote to his brother.

Doctor Paul Gachet (1890), Vincent Van Gogh. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay. Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

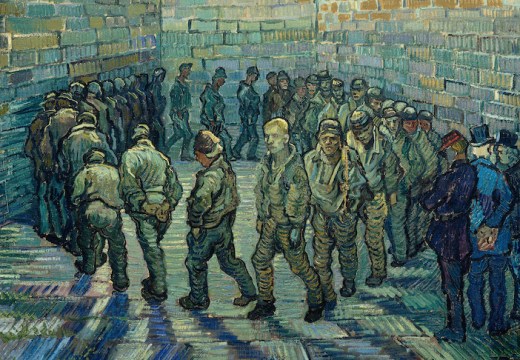

Van Gogh came to be in Gachet’s care after cutting off his ear and spending a year in asylums in the south of France, where he suffered delusions of persecution and made several suicide attempts. He depicted his shadowy fellow inmates crowded around the stove of a long dormitory, curtains enveloping the beds. He compared the ward to ‘a third-class waiting room in some stagnant village’; the patients were like passengers, left to ‘vegetate in idleness’. To alleviate his own boredom he began, in the tradition of Géricault, to paint their portraits. He wrote to his brother that ‘by seeing the reality of the various madmen and lunatics in this menagerie, I am losing the vague dread, the fear of the thing. And little by little, I can come to look at madness as a disease like any other’.

Gachet was against the isolation of the mentally ill, believing they should be integrated into society and absorbed in useful activity, and he advised Van Gogh to ‘work a great deal, boldly’. Indeed, with this regimen he seemed confident that he could prevent a relapse of Van Gogh’s illness. The artist completed almost a canvas a day in his final months in Auvers-sur-Oise, 30 kilometres north-west of Paris. These works and his relationship with Gachet, who collected 27 of his paintings, are the subject of an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay (until 4 February). Theo Van Gogh had heard about Gachet from their mutual friend, the Impressionist painter Pissarro, and in a letter to his brother described Gachet – who ‘does painting in his spare moments’ and ‘has been in contact with all the Impressionists’ – as resembling and reminding him of Vincent.

Having been discharged from the Saint-Paul asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, supposedly cured, Van Gogh was happy to transfer to Gachet’s care, renting cheap lodgings near the doctor’s home. With such a qualified guardian, who had written a doctoral thesis on melancholia in 1858, the 37-year-old artist felt that he would be protected, if he had another attack, from being arrested and ‘carried off to an asylum by force’. Gachet had worked at the Bicêtre hospital for the mentally ill in Gentilly, where he painted a woman in a straitjacket, a restraining device that was invented there. He also worked at the Salpêtrière in Paris, where at the end of the 18th century Philippe Pinel unshackled the insane, no longer treating them as criminals, and developed more humane treatments. In the 1850s Gachet made quick line drawings of the ‘lascivious’ dancing of the Salpêtrière’s hysterical patients. At his suggestion, his friend Armand Gautier also created a painting set in the courtyard of the institution, depicting a cast of pathological types, which was a highlight of the 1857 Salon.

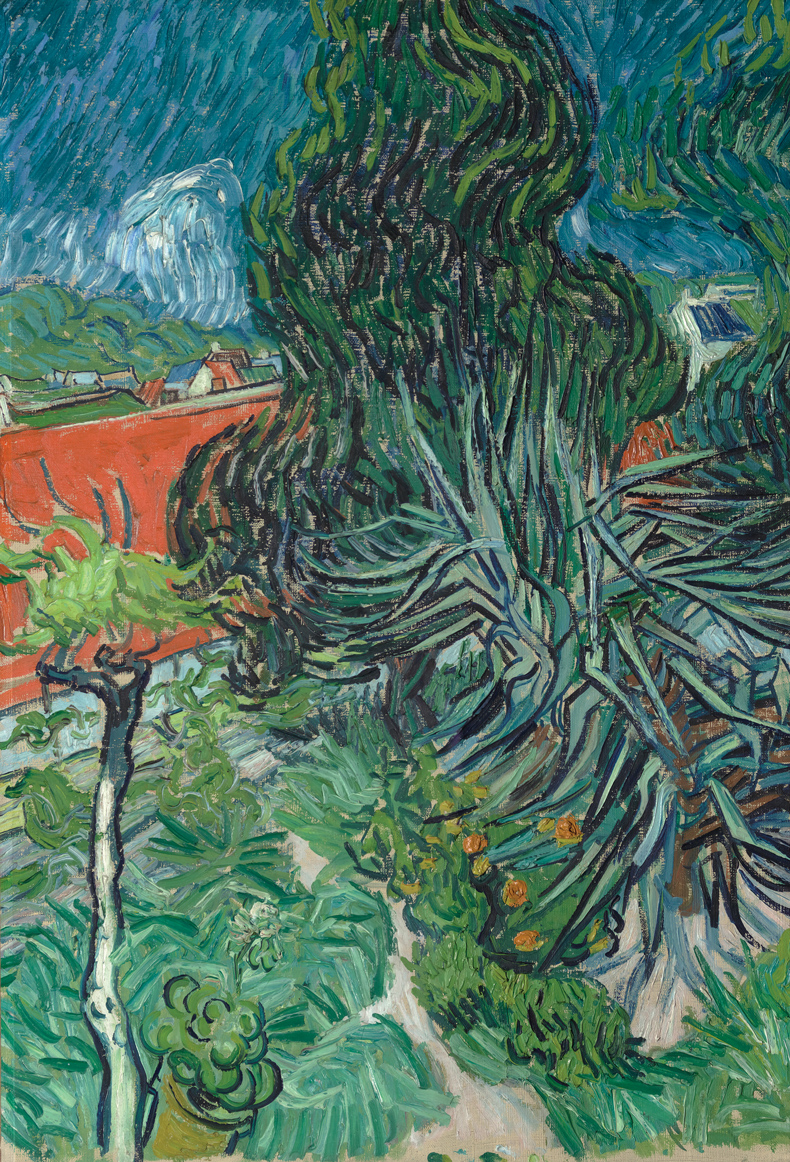

In the Garden of Doctor Gachet (1890), Vincent Van Gogh. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay. Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

Through Gautier, Gachet met Courbet and other artists. As their friend, doctor and patron he amassed a large collection of works by Cézanne, Guillaumin, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley. A lecturer of anatomy to artists, he also collected phrenological casts of the severed heads of executed criminals. Gachet was himself an amateur printmaker, creating works under the pseudonym Paul van Ryssel. In the 1850s he visited the engraver Charles Meryon, famous for his views of Paris, in the asylum at Charenton and acquired several works by the artist, whom he diagnosed with delirious melancholia. Meryon sometimes refused to leave his bed, thinking himself marooned in a sea of blood, and had paranoid fears about a Jesuit conspiracy. He was furnished with a studio and added curious monsters, horse-drawn chariots and flying fish into the skies of his pathological cityscapes.

Van Gogh knew of Meryon, perhaps through Gachet. ‘I keep thinking of so many other artists suffering mentally, and I tell myself that this does not prevent one from exercising the painter’s profession as if nothing were amiss,’ he wrote to his brother. This was Gachet’s prescription against melancholia. But Van Gogh felt that he risked his life for his work and that ‘my reason has half-foundered with it’. In the popular imagination, especially after Vincente Minnelli’s film Lust for Life (1956), Van Gogh is the quintessential mad genius. But are Van Gogh’s paintings, with their confident, thick brushstrokes that seem to dissolve space into spiralling eddies – ‘drunken suns whirling over so many unruly haystacks’, in Antonin Artaud’s description – indicative of madness? Did he ever, as he feared he might, lose his ‘equilibrium as a painter’?

His distinctive style was developed before any bouts of schizophrenia or manic depression and few in his lifetime made the equation between his mental illness and his work. In 1911, Portrait of Dr Gachet became one of the first Van Gogh to enter a public museum, the Städel in Frankfurt, where it influenced the Expressionists of the Blaue Reiter group. It was later branded ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and sold by Hermann Göring in 1937. In their ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition the following year, the Nazis used images from psychologist Hans Prinzhorn’s The Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922), one of the first serious attempts to analyse the work of ‘schizophrenic masters’, to argue that all modern art was pathological. There was a long history of dismissing the avant-garde as mad. At the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, Cézanne’s A Modern Olympia, which Gachet owned and had loaned, was dismissed by a reactionary critic as the work of a ‘lunatic, painting under the effects of delirium tremens’.

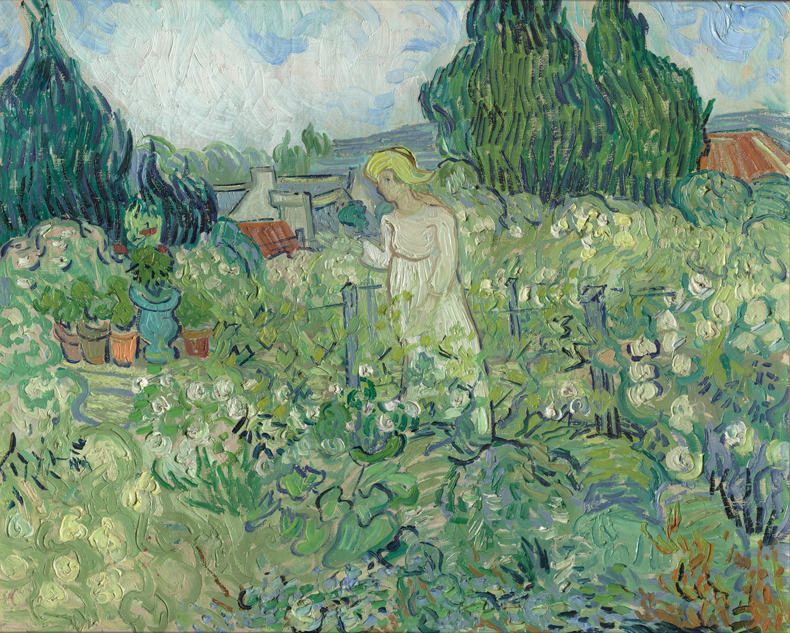

Mademoiselle Gachet in her Garden in Auvers-sur-Oise (1890), Vincent Van Gogh. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay. Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

When he visited Gachet’s house, Van Gogh was struck by the melancholy gloom, ‘full of black antiques, black, black, black except for the Impressionist pictures’. They bonded over an enthusiasm for Delacroix’s Tasso in the Madhouse (1839), which Van Gogh had visited with Gauguin in Montpellier and which Gachet had seen many years earlier with Courbet in the house of Alfred Bruyas, the collector he emulated. Van Gogh, who chose to portray Gachet in a similar pose to Tasso, felt that he had found ‘a true friend in Dr Gachet, something like another brother, so much do we resemble each other physically and also mentally’.

Van Gogh described Gachet to his actual brother as ‘rather eccentric, but his experience as a doctor must keep him balanced enough to combat the nervous trouble from which he certainly seems to be suffering at least as seriously as I’. He attributed Gachet’s depression to his having lost his wife 15 years earlier. Van Gogh had a near total identification with Gachet; however, knowing his own precarious mind, this did not instil confidence. A few days later Van Gogh wrote again to his brother saying that he thought Gachet unreliable because ‘he is sicker than I am, I think […] Now when one blind man leads another blind man, don’t they both fall into the ditch?’

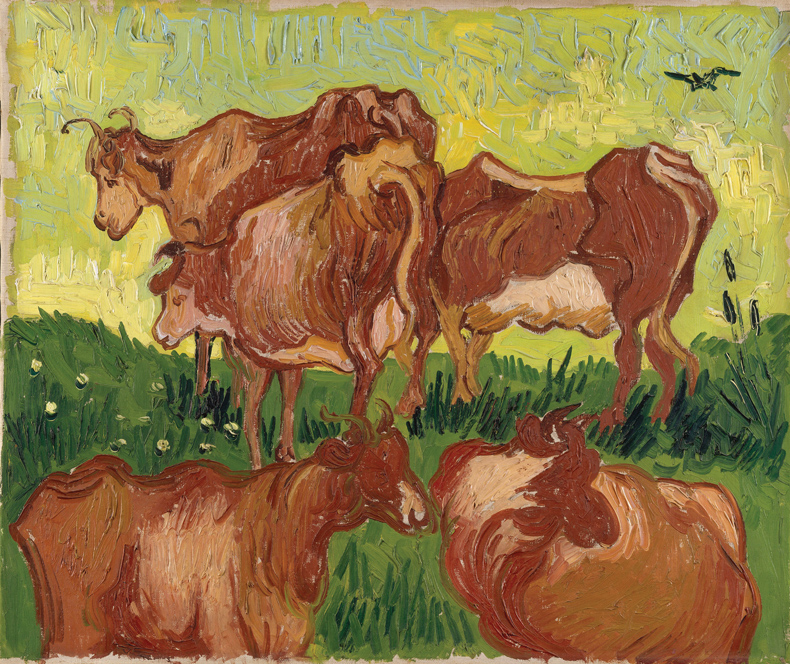

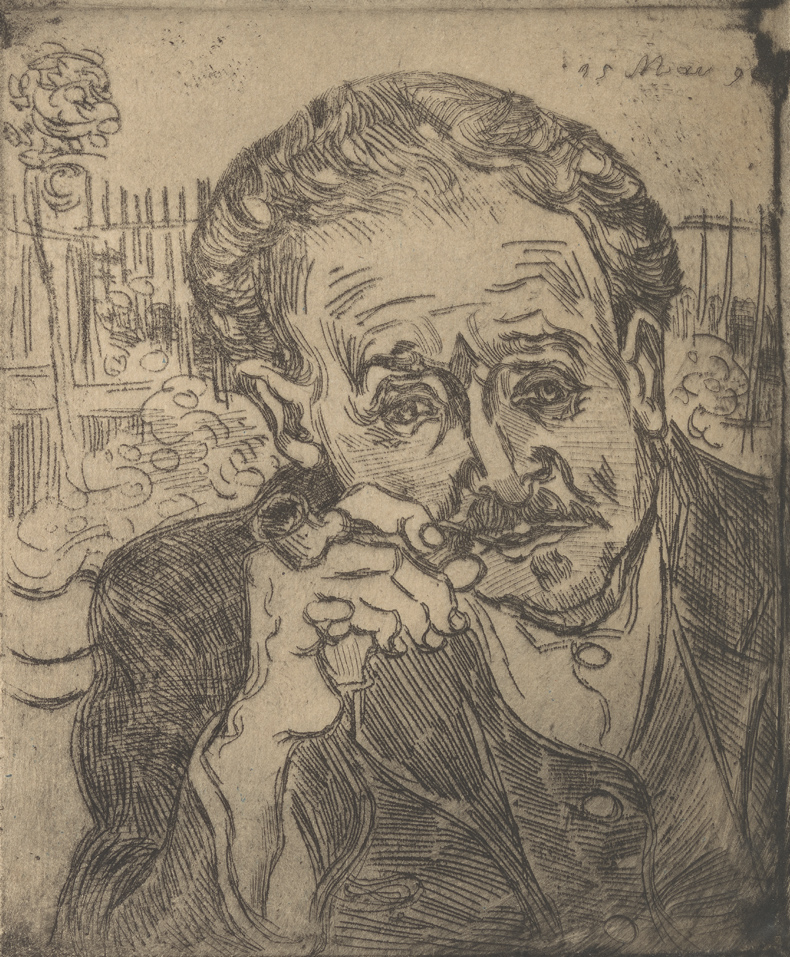

In Auvers-sur-Oise, hoping to renew himself in nature, Van Gogh painted images of the local church, ‘violet-hued against a deep sky-blue colour, pure cobalt’, as well as numerous thatched homes, like ‘human nests’. He painted The Cows based on a print Gachet had made from a painting by Jacob Jordaens that the physician had seen in his hometown of Lille. Van Gogh also made a portrait of Gachet’s 19-year-old daughter Marguerite at the piano against a green background dotted with measles-like spots, an idea suggested by an etching Gachet had made of his wife. Following in the tradition of Cézanne and Pissarro, who made liberal use of Gachet’s well-equipped printmaking studio in the attic of his house, Van Gogh made Portrait of Dr Gachet (Man with a Pipe) – his only etching, which he reproduced in a variety of colours.

The Cows (after Gachet, after Jordaens) (1890), Vincent Van Gogh. Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais/René-Gabriel Ojeda

It came as a surprise to Gachet when Van Gogh shot himself in the chest, hauling himself back wounded to his auberge, and he kept vigil until the artist died two days later, on 29 July 1890. According to Émile Bernard, who came to Auvers for the funeral, Van Gogh, smoking a pipe in his death throes, claimed to have fired the shot deliberately, in ‘complete lucidity’. When Gachet said that he hoped to save him, Van Gogh replied, ‘Then I’ll have to do it all over again’. Though a skilled dissector of bodies, Gachet made no attempt to remove the bullet. At the funeral, Gachet put a bouquet of sunflowers on the coffin and, according to Bernard, perhaps suffused with guilt as well as grief, ‘could only stammer a very confused farewell’.

The Surrealist poet and artist Antonin Artaud, who spent nine years in mental hospitals, saw an exhibition of Van Gogh’s work in 1947, the year that some of his own aberrant drawings showing delirious and disrupted bodies were also exhibited in Paris. Artaud’s schizophrenia had been a rude reminder to the Surrealist friends who visited him that their romantic idea of madness as marvellous imaginative freedom conflicted with the harsh realities of delusional states. In objection to a review written by a psychiatrist dismissing Van Gogh as ‘degenerate’, as the Nazis had done a decade before, Artaud came to the artist’s defence in an angry stream-of-consciousness diatribe, ‘Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society’.

Artaud admitted to identifying with Van Gogh and saw in Gachet his own psychiatrist Dr Gaston Ferdière, who had given him electroconvulsive therapy at Rodez hospital. Ferdière called for the foundation of a museum of psychopathological art, reflecting a growing interest in the art of the insane, and he encouraged Artaud to write and paint. Artaud, who admitted to wanting to kill Ferdière, branded Gachet a murderer: ‘And yet more than ever I believe it was because of Dr Gachet of Auvers-sur-Oise, because of him, I say, that Van Gogh […] departed this life.’

Portrait of Doctor Gachet (Man with a Pipe) (1890), Vincent Van Gogh. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Kröller-Müller

In the 1950s, retired naval officer Louis Anfray repeated these accusations in a series of sensationalist articles, based on supposedly suspicious elisions in Van Gogh’s published letters which turned out to be innocent editing mistakes. He also questioned the authenticity of many of the Van Goghs that Gachet’s children had donated to the French state in the early 1950s and which were exhibited at the Orangerie in 1954. These included the hastily painted The Cows, a second portrait of Gachet based on the first, now in the Orsay, and the etching of Gachet smoking a pipe, which is dated before Van Gogh arrived in Auvers. He doubted Van Gogh could have been so prolific in his final days and because the family were all enthusiastic copyists he insinuated that they were also forgers and exploiters of his legacy.

There is some indication that like Artaud, Gachet also identified with Van Gogh. He sketched the artist on his deathbed and in a letter of condolence to Theo he compared the artist to the Stoic philosopher Seneca, who also committed suicide and suffered a slow death by bleeding. He described Van Gogh as having a proud ‘sovereign disdain for life’ and admitted that he too was sometimes tempted by ‘the void’ that had consumed him. When Theo’s wife published the correspondence between the two brothers that would become famous, she wrote that nobody understood Van Gogh better than Gachet.

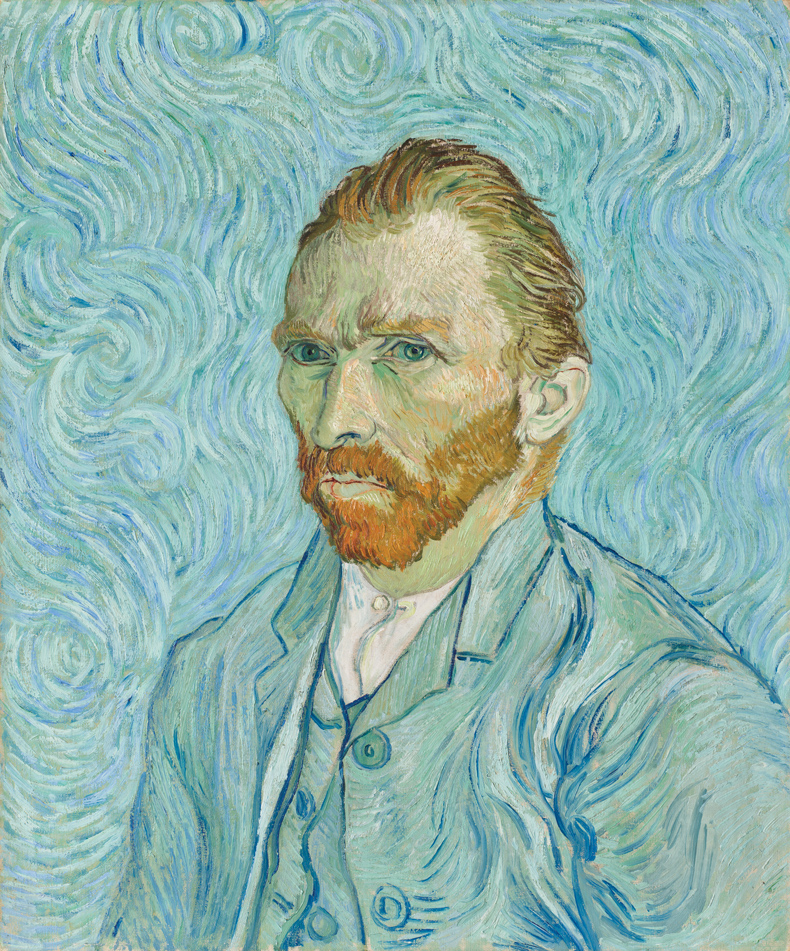

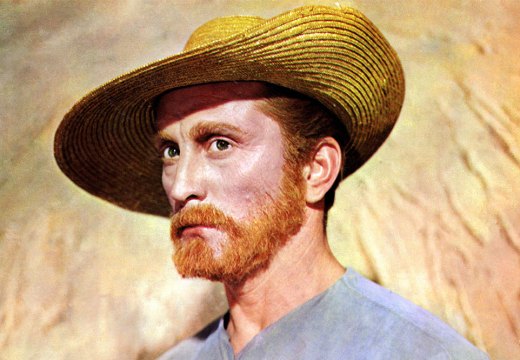

Self-Portrait (1889), Vincent Van Gogh. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay. Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

Gachet, who declared Van Gogh to be ‘a giant’, devoted the last years of his life to an unpublished biography of the artist. His collection remained sequestered in his house but in 1905, four years before his own death, for the first and only time he lent two portraits to a retrospective of Van Gogh’s work. These were the portrait of himself with a grief-furrowed face and the self-portrait the artist had made in Saint-Rémy the year before, his head haloed in blue swirls, which Gachet acquired from Theo right after the artist’s death (Fig. 2). It was as if he wanted to link himself irrevocably with Van Gogh, as a kind of alter ego and witness to his final days. The melancholy, red-headed doppelgängers, Van Gogh wrote, were painted with the ‘same sentiment’.

From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?