A preview from our September issue…

At the time of writing, the Rio Olympics are in full swing. And as so often with today’s sporting pageants, these games have been supplemented by various official cultural projects – which in Rio include three artists-in-residence, 13 posters by Latin American artists, and a mural almost 200 metres long. For all that the International Olympic Committee’s current agenda entails forging closer ties between sport and culture, such efforts tend to feel tokenistic: more like the type of window-dressing to which property developers so often resort than serious attempts to consider the subtleties of sport with any artistic nuance.

The early games of the Olympic modern era included artistic competitions, in which artists, architects, writers, and musicians contended for medals, submitting works that had been inspired by sport. These awards were curtailed after 1948, with the arts then deemed professional pursuits and so contrary to the amateur spirit of the games. But that moment is also a symptom, I think, of a wider cultural transition that took place in the 20th century, whereby sport was increasingly seen as a tenuous, even trivial subject for art (with the exception of photography). No painter in recent decades has captured how swiftly heroism can deflate to shame in sport in the way that George Bellows did in his boxing paintings at the start of the last century. The Futurists were probably the last major movement to take sport seriously, with their obsession about where man met machine, saddled up on a bicycle.

The decline of sport as an artistic subject is strange in its way, given how much noise it has come to make in our culture at large. At a time when almost every aspect of life seems to be audited by contemporary artists before being transformed – with varying degrees of success – into art, few recent artworks have been able to engage with sport without succumbing to triteness. One exception is Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2005–06), the film by Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno in which 17 cameras stalk the footballer Zinedine Zidane for the full 90 minutes of a game; this is a work of great sympathy for the intensity of professional sport, which recognises and relays both the extreme physical demands on an elite sportsman’s body and the pressure on performing under continuous scrutiny.

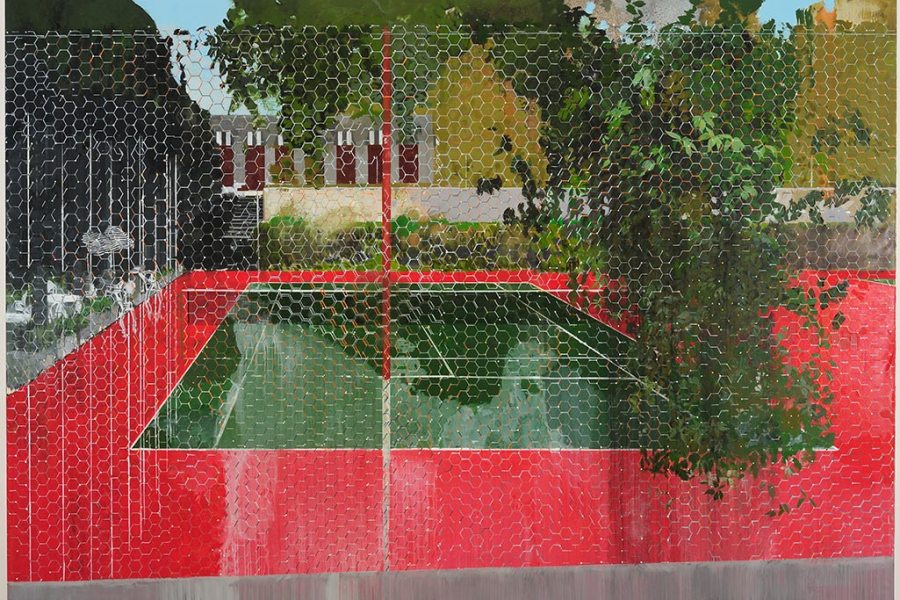

Some contemporary painters, too, have created works that dwell on sport, the best of them capturing how it is at once peripheral and central to many of our lives. In Country Club: Chicken Wire (2008), Hurvin Anderson – who is interviewed by Alice Spawls in our September 2016 issue – depicts a deserted tennis court behind an impenetrable wire fence, a reminder of how the spaces in which sport takes place have become ubiquitous but continue to mark out social boundaries. In the vivid dreamscape of Cricket Painting (Paragrand) (2006–12), Anderson’s former teacher, Peter Doig, grasps sport’s capacity to reach beyond daily life to shape our memories and imaginations.

Both paintings are a far cry from the type of sporting art that hangs in clubhouses and pavilions across Britain. Indeed, the widespread turn away from sport as a subject has coincided with this historical genre falling out of fashion (it already seemed arcane to leading figures of the modernist movement). Paintings by artists from Wootton to Munnings may remain collectible, but are now low on the curatorial agenda at most museums and galleries – perhaps understandable, given that viewers today find it hard to see beyond the rarefied pursuits of yesteryear’s elites when faced with such canvases.

But given how significant sporting art is to the history of art in Britain, it is encouraging news that a long-planned heritage centre for horseracing and sporting art is to open at Palace House, Newmarket, this autumn, in what remains of Charles II’s sporting palace and racing stables. This will include the Fred Packard Museum and Galleries of British Sporting Art, which will show works from the British Sporting Art Trust. I hope it puts forward a case for the artistic merit of the collection, however unorthodox such a stance may now be, and helps us to reconsider the relationship between art and sport in the present.

This is a preview from the September issue of Apollo: subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?