With some 300 works, this exhibition considers Cubism from many angles. It looks at the influence of Paul Cézanne upon Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in the movement’s early years – but it also looks beyond the work of these pioneers to consider the lasting impact of the movement on artists as disparate as Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich and Marcel Duchamp. Find out more about ‘Cubism’ from the Centre Pompidou’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | See Apollo’s Picks of the Week here

Kitchen Table (1888–90), Paul Cézanne. Photo: Hervé Lewandowski; © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay)

The Cubists were influenced by the primitivist paintings of Paul Gauguin, and by the geometric, abstracted forms of traditional sculpture from Africa and Oceania – but it was the late style of Paul Cézanne that perhaps most pointed the way forward for Picasso and Braque. Cézanne’s work marked a departure from classical modes of representation in painting; he broke down the objects and landscapes he saw in front of him into solid, geometric blocks of colour.

Pitcher and Vilolin (1909–10), Georges Braque Photo: Martin Buhler; courtesy Kunstmuseum Basel; © ADAGP, Paris 2018

By 1909, the first works in a true Cubist style had been completed. This painting by Braque – an exceptional loan from the Kunstmuseum Basel – demonstrates many of the style’s most recognisable characteristics; two simple still-life subjects (a pitcher and a violin) have been analysed from multiple viewpoints, deconstructed, and reassembled in a complex, architectonic structure on the canvas.

Woman on Horse (1912), Jean Metzinger. Photo: courtesy SMK Photo; © ADAGP, Paris 2018

Along with Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger became one of the principal theorists of the new movement. The two writers published the first text on Cubism in 1912, which advanced the influential argument that this new kind of pictorial representation, often termed ‘analytical Cubism’. As with the Braque painting above, this depiction of a woman on a horse gives the viewer the impression of apprehending the scene from every possible angle simultaneously.

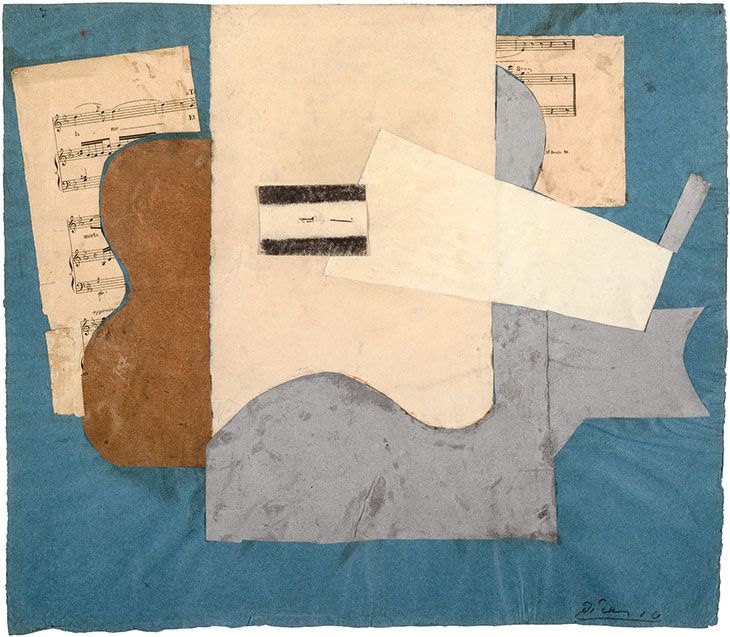

Sheet music and guitar (1912), Pablo Picasso. Photo: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Adam Rzepka/Dist. RMN-GP; © Succession Picasso 2018

When Picasso and Braque began to create collages, assemblages and constructions in 1912, they moved beyond ‘analytical Cubism’ and developed what has become known as ‘synthetic Cubism’. Rather than presenting an ‘analytically’ constructed image of their subject, this picture plants an idea of its subject in the viewer’s mind by synthesising suggestive shapes – curved masses for the guitar’s body; a trapezoid for the fretboard – with found objects that have a symbolic association with the subject (here, cut-up scraps of sheet music).

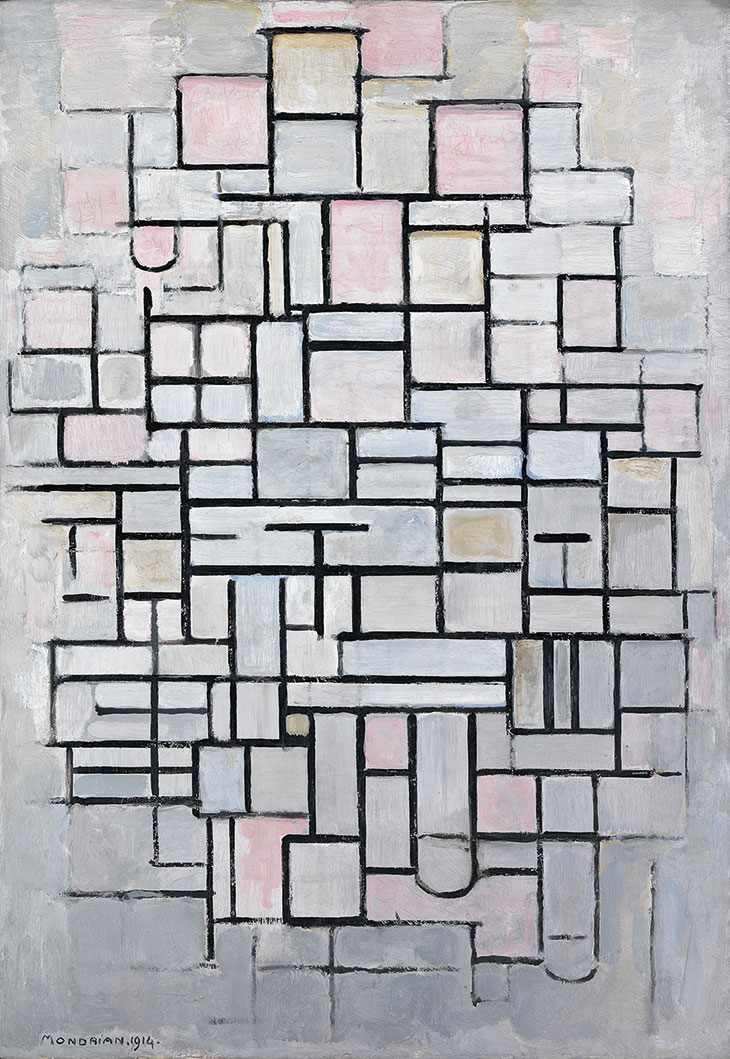

Composition IV (1914), Piet Mondrian. Photo: © Gemeentemuseum, La Haye/Bridgeman Images

Cubism is generally held to have ended with the beginning of the First World War in 1914. Though short-lived, the movement’s influence on the subsequent development of modern art was profound. Its confrontation of traditional, static representation would influence movements like Dada and Surrealism, which emphasised the role of the imagination in art. Most pointedly, however, it stimulated the development of abstraction, as this early work by Piet Mondrian, with its densely packed structure of simple geometric forms, attests.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Valadon’s shifting gaze