At the age of four, Danh Vō fled South Vietnam with his parents aboard a homemade boat. They were intercepted by a commercial tanker and given safe passage to Denmark, where he grew up. The tale shares something of the drama and anguish of Joseph Beuys’ famous account of being rescued from a plane crash in the Crimea by Tatar tribesmen. Except that in Vō’s case, the incident was entirely real – even if he has no memory of it – and has proved key in shaping his artistic concerns.

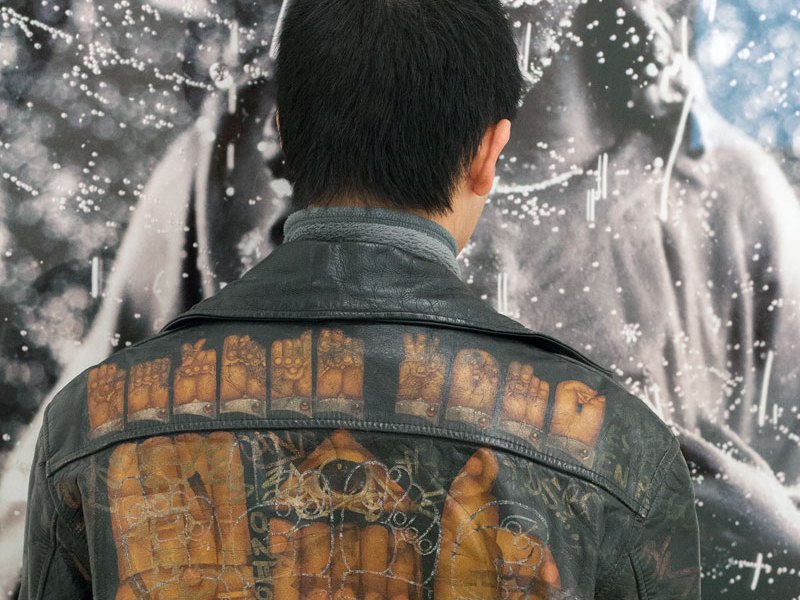

Questions of identity, displacement and memory are ever-present in Vō’s art. He has commented that ‘I see myself, like any other person, as a container that has inherited these infinite traces of history without inheriting any direction.’ When he scooped the coveted Hugo Boss Prize in 2012, Guggenheim chief curator Nancy Spector praised his ‘transnational sensibility’, and that sensibility has been most vividly reflected in his grandiloquent work We the People (2010–13) – a recreation of the unassembled sections of the Statue of Liberty in crisp copper sheeting. The discrete fragments were distributed to exhibitions in far-flung countries. A similar idea of expropriation and disassembly lay behind a 2009 installation in which Vō obtained a chandelier from the room where the Paris Peace Accords of 1973 were signed (supposedly ending the Vietnam War), and carefully laid out its myriad separated parts.

Brought up in Denmark, Vō later studied at the Städelschule in Frankfurt and was based in Berlin for several years. ‘I grew up artistically in Berlin,’ he recalls: ‘I had a lot of good brains around me who are still there.’ More recently he has been based primarily in Switzerland and New York, although he continues to travel frequently. In art and life alike, nationality appears of small importance: ‘Good art transcends borders – and that includes national identity, which I’m not a big fan of’, he states: ‘But I don’t think that excludes the idea of being local.’ He points to the veteran Italian artist Carol Rama as an artist who ‘has lived her whole life in Turin in the same flat, for more than 70 years, and has an amazing body of work,’ adding that ‘Goethe was the same’. (He has recently been involved in installing an exhibition of Rama’s works at Nottingham Contemporary, alongside a solo exhibition of his own – his first major UK show). The transnational Vō will represent Denmark at the 2015 Venice Biennale; he is impressively insouciant – or perhaps understandably tight-lipped – about what he has planned: ‘If only I knew!’

‘In the end,’ Vō muses, ‘transcending national or local borders is not actually my focal point – transcending time is far more complex.’ And indeed a variety of different histories – Vō’s own and those of others – permeate his art, which repeatedly lays bare the power or pathos of the ‘incidental object’ (take the broken chandelier in all its forlorn pomp). His 2013 exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim Museum took the form of a homage to the late painter Martin Wong, with Vō displaying a hoard of curios that Wong lovingly amassed over several decades, from books and paintings to kitsch ceramic figurines. The project exemplified Vō’s willingness to celebrate the artistic voices and endeavours of others. He points out that Wong himself ‘was able to speak in multiple languages at the same time, in a way that only people experimenting with LSD can’, and he clearly sees the absorption of other voices as a vital aspect of making art. ‘I have no desire to hide the fact that a lot of friends – among them artists – are a part of formulating my artist language.’

James Cahill

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.