Andy Warhol. Robert Rauschenberg. Jasper Johns. William S. Burroughs. John Giorno, the poet and performance artist, slept with them all. These romantic connections were sometimes ‘transcendent’ (Giorno’s words), of a piece with his lifelong commitment to Buddhism; sometimes, he found himself awed by the personality of the great artist. But it was all, as Giorno recounts in his posthumously released memoir Great Demon Kings, deeply joyful: passionate embraces, urgent disrobing, and hot, ecstatic love-making.

Of course, John Giorno, who died at the age of 82 in late 2019, was much more than the sum of his sexual conquests. The author of several books of poetry, and star of Andy Warhol’s film Sleep (where, for over five hours, Giorno does just that), he is best known for his projects with Giorno Poetry Systems. Inspired by the groundbreaking ‘9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering’, a series of performances held in New York in 1966 that experimented with the artistic possibilities of new media technology, Giorno’s artistic collective took a similar approach to poetry and sound. Their most well-known project, Dial-A-Poem – a phone service set up in 1968, in which callers could listen to readings by Frank O’Hara, John Cage, and others – is still running today at (+1) 641 793-8122. Giorno was a key figure bringing the technological strategies of mass communication, already revolutionising the art scene, to the spoken word.

Of course, John Giorno, who died at the age of 82 in late 2019, was much more than the sum of his sexual conquests. The author of several books of poetry, and star of Andy Warhol’s film Sleep (where, for over five hours, Giorno does just that), he is best known for his projects with Giorno Poetry Systems. Inspired by the groundbreaking ‘9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering’, a series of performances held in New York in 1966 that experimented with the artistic possibilities of new media technology, Giorno’s artistic collective took a similar approach to poetry and sound. Their most well-known project, Dial-A-Poem – a phone service set up in 1968, in which callers could listen to readings by Frank O’Hara, John Cage, and others – is still running today at (+1) 641 793-8122. Giorno was a key figure bringing the technological strategies of mass communication, already revolutionising the art scene, to the spoken word.

In the early ’60s, Giorno had seen his chosen medium as dead on the vine: ‘Hanging out with my artist friends, it was clear that poetry was seventy-five years behind painting, sculpture, music, and dance,’ he writes. And yet, poetry had already begun espousing more progressive values, which were still absent from the art world. Giorno describes himself as ‘part of the generation liberated by Allen Ginsberg’s Howl’ – he runs through a park yelling with glee after reading it, and it sets the tone for the radical sexual openness he would explore in works such as Pornographic Poem (1964). In contrast, the artists Giorno dated kept their love lives quiet, and avoided open discussion of sexuality in their work. In his recollections Giorno, the son of well-off and supportive Italian Americans, is often frustrated by the art scene’s homophobia, though he never blames those oppressed by it. Giorno suggests to Warhol again and again that he work with homoerotic images: the artist turns the idea down every time, scared of being ostracised. ‘Andy […] realized that being a gay artist was the kiss of death. Gay was a subculture, and a dead end; Andy wanted popular culture,’ Giorno writes.

Not so Giorno, whose matter-of-fact, sincere descriptions of his prolific sex life are filled with juicy particulars. He takes his time to describe the desires, genitals, and orgasms of these men in luminous detail, and clearly delights in mining these encounters for gossip: Andy Warhol’s preference for giving blowjobs, Burroughs’s premature ejaculation. The book is shot through with the poet’s pornographic memories: uninhibited ribbons of sex lighting up his descriptions of his youth.

If his sex scenes are explored in matter-of-fact detail, Giorno’s descriptions of his early New York years have a similarly beady eye for the ins and outs of social groupings, connections, invitations and exclusivity. His own creative inspirations and work are often explored through the mirror of his relationships: his project Dial-A-Poem is first mentioned as the reason that he can’t call Jasper Johns back, for example, and his collection Cancer in my Left Ball (1970–72) appears as an epilogue to the titular event, the writing of its poems barely mentioned. Giorno shares his behind-the-scenes knowledge of the production of others’ artworks – the sharing and trading of ideas, how they proliferate through a social scene (the concept for Warhol’s Thirteen Most Wanted Men mural of 1964 was suggested by the painter Wynn Chamberlain, who was dating a New York City cop). And yet when it comes to his own output, the product often appears to arrive in his memory fully formed.

The cover of the January 1964 issue of Film Culture, featuring a still photo from Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1964). Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Despite his ease with his sexuality, Giorno is consumed with a different kind of anxiety – that he is a tag-along, only interesting because of the more powerful men he dated: ‘This was shaping up to be a lifelong syndrome,’ he writes, after recounting an incident in which he was asked to perform at NYU’s Loeb Student Center – and to get Robert Rauschenberg involved, too. Giorno: ‘“No!’ I shot back. “Bob doesn’t perform any more”.’ In his memoir, he emphasises the purity of his intentions in his relationship. ‘I would have loved to have it, but I didn’t want any implication that I was in it for material gain,’ he writes, when Rauschenberg forgets to send him an edition of his hugely influential print Booster (1967) as promised. ‘I was the whore with the golden heart, no money, and I gave double. I was there only because I loved Bob’s body and mind.’

The tone changes in the books’s last quarter, as Giorno’s long-term interest in Buddhism culminates with a trip to India in 1971 (although he still treats a meeting with the Dalai Lama in his old, gossipy fashion – as an encounter of personalities and awkwardness). Having struggled with depression his whole life, and having attempted suicide in his youth, Giorno sees this trip as a spiritual turning point – the beginning of a quieter, more contented life, in which his meditation practice took precedence over his sex drive. The book’s narrative speeds up considerably after this point, obscuring the reader’s view of these later years: the testicular cancer, the final years of his enduring friendship with Burroughs, but also some of his most significant work, and happiness in his 22-year partnership with Ugo Rondinone.

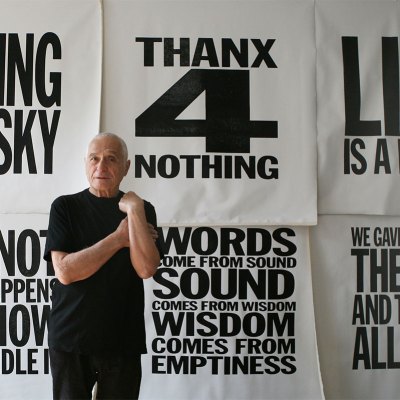

Despite the fears he expresses, it’s difficult not to read Giorno’s life as that of a lover and archivist for other men, those ‘great demon kings’. For fans of his work, it’s frustrating how he declines to claim the crown for himself: an experimenter who at one point (while working with Bob Moog, inventor of the first commercial synthesiser) attempted to include sphincter-releasing frequencies in his poetry recordings, and has inspired myriad contemporary artists – many of whom paid him homage in the show ‘I ♥︎ John Giorno’, organised by Rondinone at the Palais de Tokyo in 2015.

The audiobook version of Great Demon Kings includes three archival recordings of Giorno reading his own poems, written in the last 20 years, when the poet believed he did his best work. His sincerity and charisma shine through the strength of his words, marking him as one of the greats of poetry. His memoir shows him treating the role with cheerful candour, as a product of fluke connections and luck, rather than a birthright. ‘A reluctant king; thank you, but no thank you,’ as he puts it.

Great Demon Kings: A Memoir of Poetry, Sex, Art, Death, and Enlightenment by John Giorno is published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. The audiobook, featuring archival recordings of Giorno’s poems, is published by Macmillan Audio.