Manila, Philippines

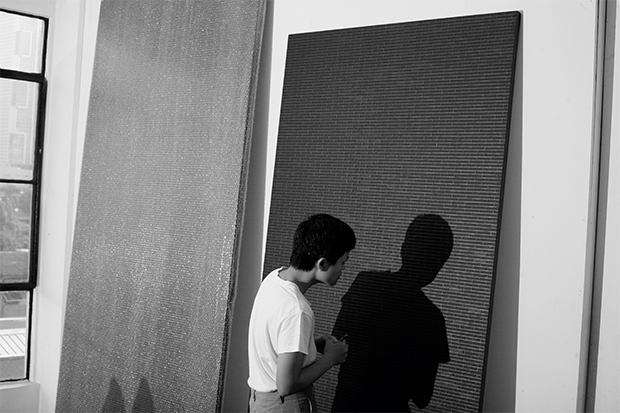

A brick wall, high and impenetrable, is not the classic image of an artistic breakthrough. Yet for Maria Taniguchi, a long-running series of paintings of bricks has propelled her – slowly and surely – to international recognition. She has been making the works since 2008, on the floor of her studio, applying acrylic paint to miniature rectangular cells (the largest such canvas measures nearly five and a half metres wide). ‘There wasn’t really a plan to make a long-term painting project in 2008, when I started them,’ she explains. ‘I had ideas about how objects, including painting, responded to space and its immediate architecture; and there was also something I wanted to express about systems and the structures surrounding making artwork. So it’s really work about making work.’

Systems and structures – the often-overlooked mechanics of things – have remained the prevailing fascination in a practice that straddles painting, video, pottery, and installation. Taniguchi comes across as the opposite of the hustling contemporary artist. Born into a family of sculptors in the Philippines, she took to art instinctively and organically: ‘It followed naturally since I was surrounded by people interested in art. The choices I made were nothing to do with making a career out of it.’ At 14, she took up a scholarship at an art school in Manila, and then embarked on a BFA in sculpture at the University of the Philippines: ‘I was a less than ideal student,’ she remembers. ‘I spent eight years barely finishing the course.’

Out of this faltering beginning came an MFA at Goldsmiths. ‘I’m very attached to London,’ she says. ‘It will always be a second home, as it is for many artists who move in and out of its orbit.’ She points to David Medalla – among the best known of Filipino artists – as a model of the émigré artist: ‘He published Signals, a journal of artists’ writings, in London in the early ’60s. I’ve been going through them, and the issues are ridiculously cosmopolitan, with collaborators like Lygia Clark, Takis, Carlos Cruz-Diez. London has always had that particular kind of energy and artistic population.’ (Her own work is gravitating more towards the written word – she recently penned a short story for an anthology conceived by the artist Heman Chong.)

Since 2010, Taniguchi has worked primarily in Manila. ‘My choice was to find a more practical place to be based in – it’s the same story as most young artists coming out of school,’ she explains. ‘And for me, it’s ideal to be a bit buffered.’ It would be easy to typecast her as a curator’s dream – rooted in the Philippines yet attuned to the global art world. But she shies away from the usual clichés about contemporary art’s sprawling internationalism. ‘We all have to look outwards to be international,’ she admits. ‘There’s been an Asia obsession in the last five years, and while I’d like to think of it as openness, it’s also a search for new ground. But Asia has always had a rich art scene – the proliferation of non-profit, alternative art spaces of the late ’90s in southeast Asia is an example.’ Taniguchi has recently added her own initiative to this tradition, an exhibition platform called Telenovela (conceived with Pio Abad), dedicated to presenting the work of forgotten artists.

Taniguchi’s work itself seems to resist easy interpretation, establishing subtle connections between products and processes, while sidestepping the reductive categories of art speak. Her video Figure Study (2012) reprises the idea of slow, repetitive labour: two men dig a hole in the jungle, silently collecting sacks of clay against the noise of cicadas. In a recent group exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design in Manila, the video appeared alongside two ‘minimalist’ slabs of clay, in such a way that the vision of grinding labour belied the cool autonomy of the final objects. In a further twist, the slabs were revealed to have been fired by the artist’s mother.

Taniguchi’s career has had its own kind of steady rhythm. In 2015, she scooped the Hugo Boss Asia Art Award, and earlier this year, she staged an acclaimed solo show at London’s Ibid Projects (of eight large brick paintings). But her artistic development has been characterised by trial and error as much as success. ‘I’ve been spending time at a clay workshop in Singapore recently,’ she tells me, ‘and I’m working on making a new kiln and workshop in Dumaguete. This might be another long-term project, or it might not. I really have no idea.’

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.