On a mid-autumn morning, as the sun starts to poke above the peaks of the mountain range, the light glistens on Lake Lugano like so many diamonds glistening on a cloth of deep blue velvet. It shimmers. It’s precisely this tremulous quality of the light that is captured in the works of Giacomo Balla (1871–1958) and Piero Dorazio (1927–2005) currently on show at the Olgiati collection’s lakeside gallery in Lugano.

‘Dove la luce’ brings together 47 works from two pivotal moments in the life of two very different Italian artists: for Dorazio, co-founder of the groups Arte Sociale and Forma 1, that year is 1960, when he was chosen to represent Italy at the Venice Biennale; for the Futurist Balla, the year is 1912, when he created the Compenetrazioni iridescenti (‘Iridescent Interpenetrations’) while working on a commission to decorate the house of Arthur and Grete Löwenstein in Düsseldorf. Separated by nearly half a century, with the former working on paper with coloured pencils and watercolours and the latter on a much larger scale with oils on canvas, the two nonetheless share a particular feeling for light and motion, evoking quite a precise sensation even in the most abstract of images.

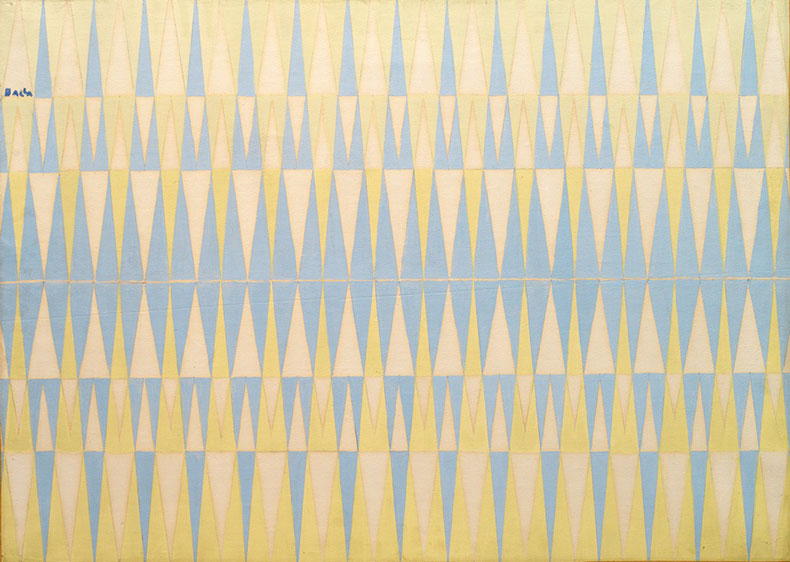

Compenetrazione iridescente n.4 (1912–13), Giacomo Balla. Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di

Trento e Rovereto, Rovereto. © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

In the post-war period, Futurism’s reputation was at a low ebb. Tarred by the association of key figures such as the poet Filippo Marinetti with Italian Fascism, few were the critics willing to mount a defence of the movement. But among artists themselves, its legacy was acknowledged in hushed tones. As a young lawyer with a burgeoning collection of Italian art, Giancarlo Olgiati was advised by his client, the nouveau réaliste Arman, to seek the origins of present concerns in the Futurist painters of the 1910s. Meanwhile, the interest of Dorazio himself in the movement was confirmed by his meeting with Balla in 1951. At his house on the via Oslavia in Rome, Balla showed his young admirer the then little-known Compenetrazioni iridescenti, now acknowledged as one of a number of works with competing claims for the first decisive break into pure abstraction.

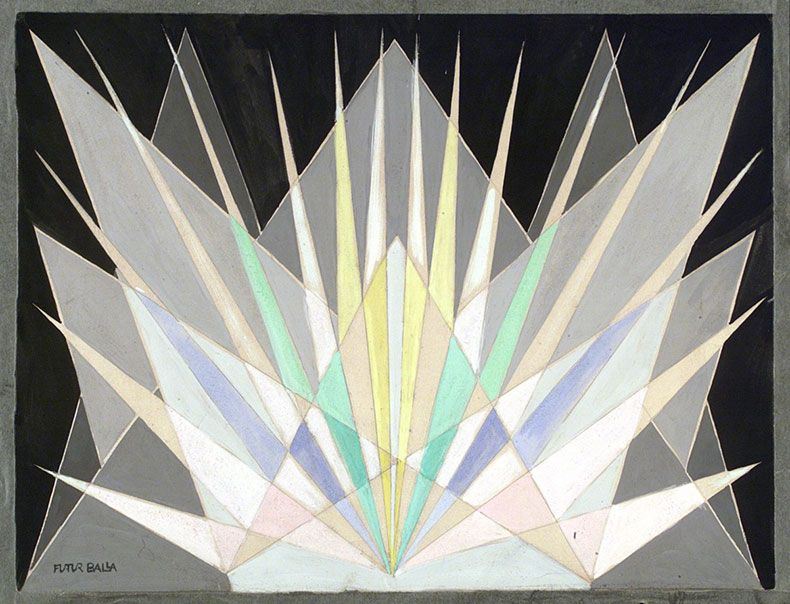

Compenetrazione iridescente radiale (Vibrazioni prismatiche) (c.1913–14), Giacomo Balla. Galleria civica d’Arte Moderna e contemporanea. © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

Even from a distance of a hundred years, Balla’s sketches leap out at you – an effect amplified here by architect Mario Botta’s innovative exhibition scenography. Casting the traditional white cube to the wind, Botta has hung Dorazio’s works on black-painted walls and set Balla’s into little vortex-like niches formed of white triangles (borrowing a motif from the works themselves) with the drawings projecting out at the viewer on arm-like horizontal stands. The Compenetrazioni iridescenti are mostly patterned like backgammon boards or other repeating geometric patterns in electrifying colours – a sulphurous yellow, the bright purple of parma violet sweets – with sharp lines and a kind of translucence hinted at through shading.

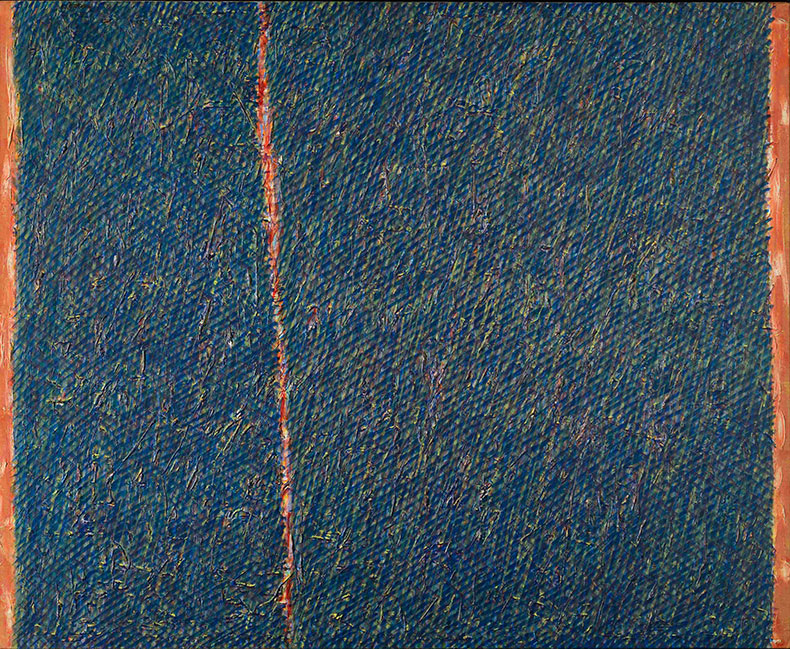

crack verde (senza titolo) (1959), Piero Dorazio. Intesa Sanpaolo Collection. © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

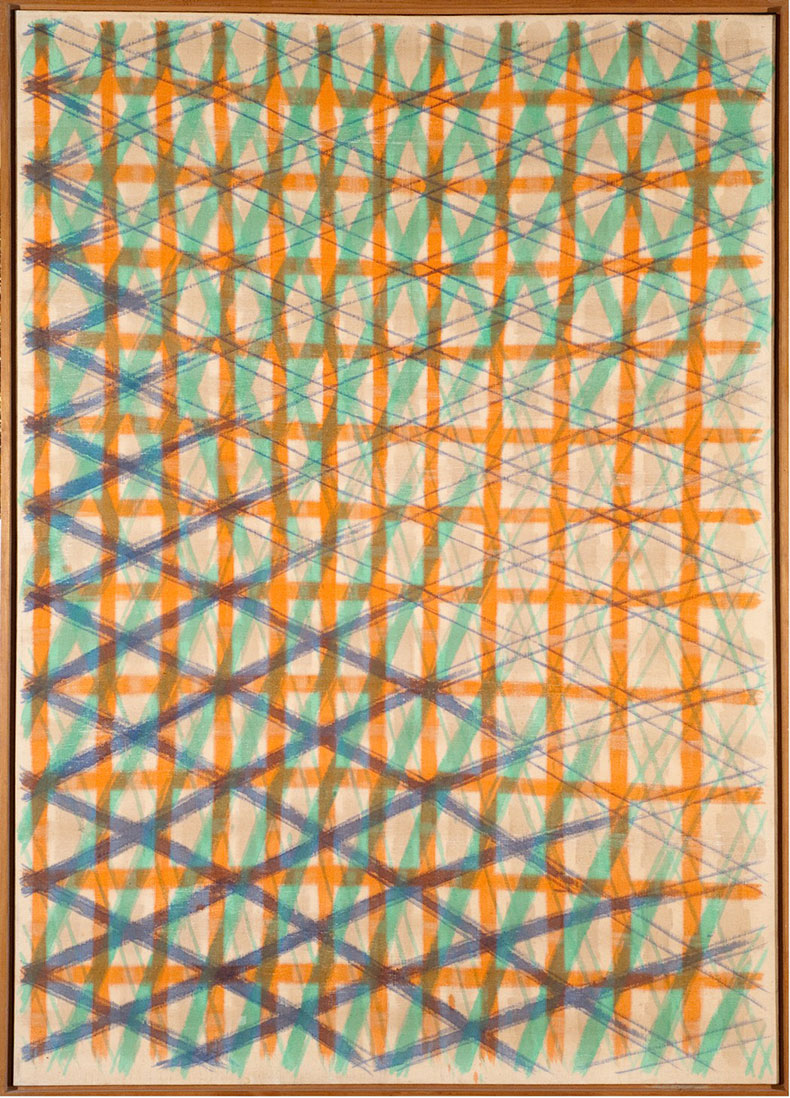

By contrast, Dorazio’s work has an almost woolly texture. Peering up close at works like sansom (1961) or crack verde (senza titolo) (1959), you can see layer upon layer of unsteady painted lines in rich contrasting primary reds, greens and yellows, forming dense thickets. From the distance of a few paces, all that painterliness disappears and they seem to quake, like dappled light through a forest canopy in high summer.

Such natural evocations are entirely absent from Balla’s images, which have an almost Newtonian approach to light, as if painted from inside a prism. But in each case, there is this fleeting, fugitive quality. Both artists capture light not so much as it looks but as it feels, and the more time one spends walking through the gallery, the superficial differences between the two seem to disappear. I am left feeling much as I did on the lake outside in the early morning light: dazzled.

Allo scoperto (1963), Piero Dorazio. Pinacoteca Corrado Giaquinto, Bari. © 2023, ProLitteris, Zurich

‘Balla ’12 Dorazio ’60: Dove la luce’ is at the Collezione Giancarlo e Danna Olgiati, Lugano until 14 January 2023.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has arts punditry become a perk for politicos?