With hundreds of exhibitions and events vying for attention in New York during Frieze and TEFAF, Apollo’s editors pick out the shows they wouldn’t want to miss

Though he referred to himself simply as an ‘American painter of signs’, the man born Robert Clark in the state of Indiana in 1928 had a knack for reinvention. His most famous ‘sign’, a rubbing of the word ‘LOVE’ in bold red type with neutral blue and green filling the space between the letters (1964), is a perfect example, asserting the word’s power even as it deconstructs it. Though the work’s ubiquity in subsequent years has threatened to diminish its effect, Indiana made countless other pieces combining words and images in ways that make us think twice about the signs and symbols that surround us. ‘Robert Indiana: The American Dream’, an exhibition at Pace Gallery (9 May–15 August), collects paintings and sculptures by the artist ranging from the 1960s to the 2010s. Some of the works derive power from their straightforwardness: The Calumet (1961) presents the names of 14 Indigenous tribes stencilled in bold circles, as if simply to assert their existence at a time when much of the American media was ignoring, justifying or glorifying their genocide. There are more ambivalent pieces too: Indiana’s sculpture The American Dream (1992/2015) comprises the words ‘HUG’, ‘ERR’, ‘EAT’ and ‘DIE’ painted on a bronze tower – a summation of human existence that somehow seems stark and comforting at the same time. – Arjun Sajip

The Calumet (1961), Robert Indiana. Courtesy Pace Gallery; © The Robert Indiana Legacy Initiative

It took Michael Armitage four years to find a non-canvas surface that gave his oil paintings the texture he desired. He finally settled on lubugo, a bark-based textile made by the Baganda people of Uganda. ‘It’s an incredibly giving surface,’ he told Apollo in 2018. ‘It interrupts the paint a lot […] You can’t have a smooth running line with thick paint.’ Appropriate, then, for an artist whose work does so much to interrupt complacent or conventional thinking. It’s hard to pass by an Armitage painting without being drawn in by currents of violence, degradation or bitter social commentary, and the works on display in ‘Crucible’, the inaugural exhibition of David Zwirner’s new Chelsea building on West 19th Street (8 May–27 June), are no exception. The show takes migration as its subject and, given the perils involved in crossing borders, Armitage’s use of lubugo takes on an added charge – it is often used in Uganda for funerary rites. Don’t Worry There Will Be More (2024) is a typically arresting treatment of the theme of migration: two naked Black men hold another aloft as waves tower behind them and a tempest rends an unforgiving sky. One of the men stares out plaintively at the viewer, while the warp of the cloth seems to not only scar the figures but also encase them – almost like a burial shroud. AS

Don’t Worry There Will Be More (2024) by Michael Armitage. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner; © the artist

Though we are used to seeing them kept inviolate in vitrines with carefully controlled temperatures and optimal lighting, medieval manuscripts were once subject to all kinds of ransacking – even by professionals. An exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum (until 15 June) sheds new light on this ostensible vandalism. It posits that when art lovers cut out images from manuscripts and pasted them into personal albums – which happened frequently in the late 19th century – it was not so much wanton damage as an act of love towards visual culture, bespeaking a desire to access and recontextualise it. The purloiners would often arrange the excised images in intriguing and imaginative ways. Even book dealers would do away with bindings and decorative initials in order to bring down weight-based import duties. Though such behaviour seems hard to justify, it’s a reminder that art-world practices are constantly evolving, and raises the question of which of our own artistic customs will seem unthinkable in 100 years’ time. AS

A page from a gospel book made in Rome (1572–85). Morgan Library & Museum, New York

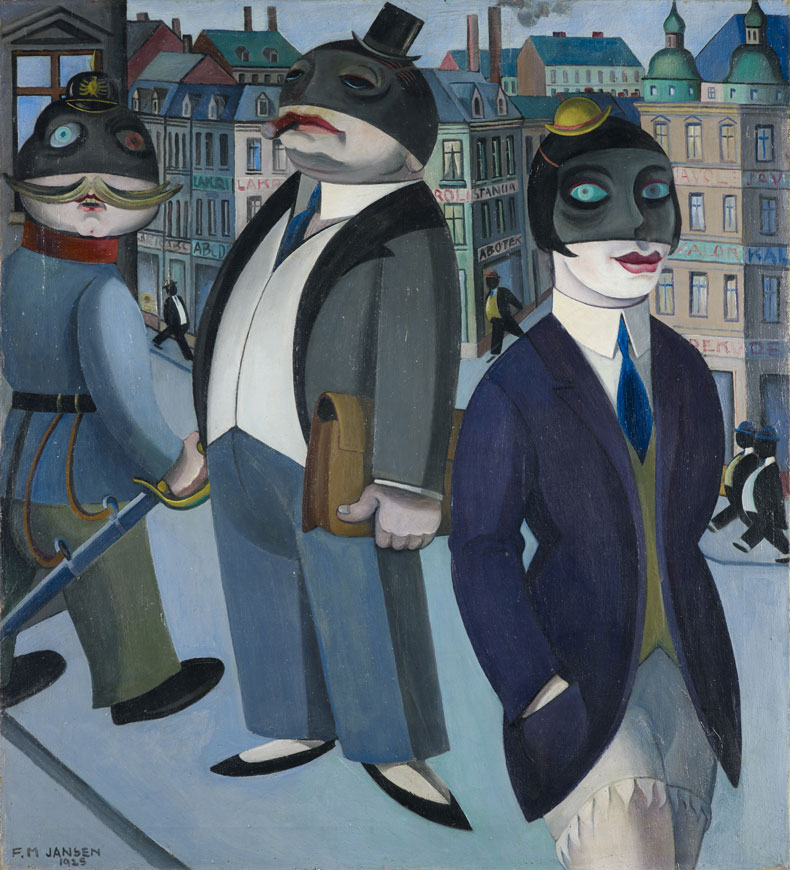

In 1925, the art historian and curator Gustav F. Hartlaub put together an exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mannheim of art that he saw as belonging to what he called Neue Sachlichkeit or ‘New Objectivity’, which he described as ‘realism bearing a socialist flavour’. These works – most of which were not really ‘realist’ in the obvious sense but rather favoured an emotional coldness and hard edges – were regarded as a reaction against Expressionism, the passion of which was felt to be an insufficient or inappropriate mode for a generation of artists who had just witnessed the horrors of the First World War. The Neue Galerie is marking the centenary of this landmark exhibition with a tribute that displays works by George Grosz, Otto Dix, Georg Scholz, Max Beckmann and others, including a portrait of an unemployed worker by Hans Grundig from 1925, Grosz’s satirical masterpiece Eclipse of the Sun (1926), and a jagged Bauhaus Stairway (1932) painted by Oskar Schlemmer, as well as Dix’s extraordinary portrait from 1926 of the prominent Berlin doctor Dr Mayer-Hermann (until 26 May). – Michael Delgado

Masks (1925), Franz Jansen. LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn. Photo: Jürgen Vogel

Robert Rauschenberg is arguably the greatest exponent of the art of found objects since Marcel Duchamp, his paintings brimming with found images and his ‘combines’ marshalling everything from newspaper clippings to light bulbs, electric fans, wooden doors and stuffed Angora goats. Perhaps because so much of his work blurs the lines between painting, drawing, sculpture and installation, comparatively little critical attention has been given to his sculptures as sculptures. (The most recent show to focus purely on his sculptural work was in 1995 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.) Gladstone Gallery is marking the centenary of the artist’s birth with an ambitious display of his sculptures, the very best of which harness what he called ‘abandoned objects’ – from scrap metal to broken chairs and decorative items – that seem random at first but coalesce into a strange kind of logic (until 14 June). MD

Twin Bloom / ROCI TIBET (1985), Robert Rauschenberg. Photo: Ron Amstutz; courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Fooundation/Gladstone Gallery; © Robert Rauschenberg/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When Mali gained independence from France in June 1960, Malick Sidibé was in his mid twenties and at the very beginning of his career. Over the next few decades he would become one of the country’s most celebrated artists; his photographs of ordinary life in post-independence Bamako were held up as defining images of an era of tumultuous change. Many of the photos on display at Jack Shainman Gallery show people smiling or in moments of revelry, though there are also several works from his enigmatic Vues de Dos series (1999–2011), in which he captured friends and family with their backs turned to the camera (until 31 May). Among the highlights of the show are some of Sidibés ‘synergistic’ works, in which his photographs are paired in colourful frames made in collaboration with local Malian artists using reverse-glass painting, which was practised in West Africa in the 19th century. MD

Grand griot N’Diaye (1979/2004), Malick Sidibé. Photo: Dan Bradica Studio; courtesy Estate of Malick Sidibé/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York; © Malick Sidibé

In the spring of 1969, New York’s Museum of Modern Art presented ‘Wall Hangings’, an exhibition of contemporary fibre art and textiles. Up until that point, few institutions had considered weaving beyond its commercial and domestic confines; MoMA did much for the medium’s reputation by situating 28 international artists ‘not in the fabric industry but in the world of art’. The exhibition was met with a mixed response, with Louise Bourgeois for one unconvinced of whether fibre art should be treated as a fine art, but as a new show at Richard Saltoun Gallery suggests, its legacy has been lasting (6 May–20 June). Here, ‘Wall Hangings’ is reprised through the work of four women who featured in the original exhibition: Magdalena Abakanowiczs’s fleshy sisal constructions and the woven cascades of Barbara Levittoux-Świderska, her Polish Textiles School peer, are joined by Olga de Amaral’s layered horsehair knits and Jagoda Buić’s sliced woollen tapestries. Also on display are woven pieces by women artists working today. Anna Perach presents a new tufted sculpture, Assemblage (2024), while Erin Manning’s hand-stitched wall reliefs from her Tactile series – interactive works designed for the deafblind community – reflect the far-reaching possibilities of fibre art. – Lucy Waterson

Tapisserie Widow (1968), Jagoda Buić. © Estate of Pagoda Buić

For Nancy Graves, it all kicked off with camels. When she was just 29 years old, the artist produced a trio of lifelike sculptures of the dromedary that captured the attention of the art world, earning her a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1969. She was the youngest person and only the fifth woman to achieve the honour. A Yale graduate and Fulbright scholar with a knack for research, she made reference to science – zoology, anthropology, palaeontology – throughout her work in the 1970s and ’80s. At Perrotin on the Lower East Side, ‘The Illusion of Motion’ traces this productive period of Graves’s career, featuring both works and archival materials that have never been shown to the public (until 31 May). The show opens with a series of pointillist paintings that reference data mined from topographical studies of the ocean floor and satellite images from NASA; later sections present large-scale colourful watercolours, which, with their aluminium fixtures extending beyond the canvas, teeter between painting and sculpture. A final section takes in Graves’s experiments with the ancient technique of lost-wax casting, with sculptures such as Nike (1983) fabricated from found objects including food and plants. LW

Nike (1983), Nancy Graves. Photo: Guillaume Ziccarelli; courtesy Nancy Graves Foundation/Perrotin; © Nancy Graves Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Those wanting a grittier glimpse in to the New York of decades past need look no further than the New York Historical’s current exhibition ‘Picture Stories: Photographs by Arlene Gottfried’ (until 25 May). Spurred on by her confidence in approaching strangers – a trait she once credited to the years she spent as a child among the eclectic crowds of Coney Island – Gottfried began photographing the streetside scenes of New York City in the late 1960s while she was a teenager. In these photographs, her inquisitive nature is transmitted through the variety of people and places she documented: prints revealing the raucous underbelly of New York’s nightclubs are presented alongside intimate depictions of Harlem’s gospel choirs and the children of Alphabet City, the Manhattan neighbourhood where Gottfried grew up. The exhibition celebrates the New York Historical’s recent acquisition of some 300 photographs by Gottfried, with the 30 images presented here looking past her work as professional photographer for publications such as the New York Times and the Village Voice to consider how she captured the soul of the city on her own terms at the end of the 20th century. LW

Eternal Light Choir Performing (1980) Arlene Gottfried. New York Historical. © Estate of Arlene Gottfried