Since 2019, Olivia Swarthout has been sharing the raucous, racy, ridiculous images that proliferate on the leaves of medieval manuscripts with a huge social media audience. Juxtaposing images of monsters, miracles and the odd anthropomorphic vegetable with dry captions, @weirdmedieval on X (formerly Twitter) and @weirdmedievalguys on Instagram offer moments of astonishment and amusement amid a stream of catastrophes, outrages and cat memes. In doing so, they connect a vast number of viewers to the extraordinary digital resources that institutions have generated over the past 25 years or so: thousands of medieval manuscripts have been fully digitised and made freely available (for those with the skills and determination to find them) on institutional platforms around the world. These include many of the world’s largest collections, such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Vatican, the Bodleian and the British Library (but more on this last in a moment).

‘Worm getting drunk, France’ – detail of folio 302r of Hours of Charles the Noble, King of Navarre (c. 1405), Master of the Brussels Initials and Associates. Cleveland Museum of Art

Weird Medieval Guys: How to Live, Laugh, Love (and Die) in Dark Times translates the social media experience into book form. The subtitle alludes to the rhyming of medieval and modern calamities (war, pestilence, famine, death) and to the didactic underpinnings of many of the images that appear in manuscripts. Even the silliest images (rabbits flaying a man; an owl bishop surrounded by apes) turn out to have roots in biblical texts and in the exemplary stories with which medieval preachers salted their sermons, as Lilian Randall demonstrated in her landmark study Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts (1966).

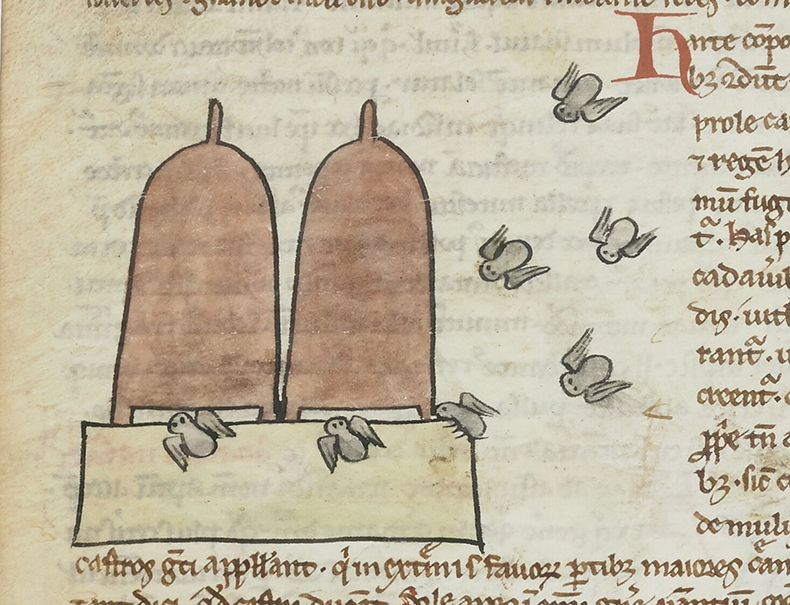

The book is organised thematically, with Part 1 focused on images and wry commentary about life, love and death. Part 2 mines the bestiary for bats, hedgehogs, mermaids and bees, with captions that combine amusingly direct descriptions (‘Boar wearing pants’) with affectionate mockery (schematically-drawn bees are ‘sweet little peanuts, flying off to their well-endowed hive’). These sections are framed by images of the Creation at the start, and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse at the end.

‘Sweet little peanuts, flying off to their well-endowed hive’ – detail from folio 64v of Anonymi tractatus de quadrupedibus, de avibus et de piscibus (1301–1400), unknown artist. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Richly illustrated and lightly written, this book will amuse its readers, but it will be up to them to discover more about the contexts in which these images were made. A list of photo credits at the end gives the institution, shelf-mark and folio reference for each of the images, but otherwise information that might enable the curious reader to dig deeper (dates, places of production, links to the digitised manuscript, notes on further reading) is absent, signalling that this a book for the humour shelf, not the (art) history reading list. This is an observation, not a complaint: such publications play a valuable part in the art-history ecosystem, drawing new voices, perspectives and audiences to material that is otherwise largely the preserve of specialists and their students. And who wants to be a vibe-killing bibliographer-art historian, popping up in the feed with facts and corrections? In its way, Weird Medieval Guys follows the tradition established by medieval preachers and artists themselves: laughter, wonder and a little shock now and then can spark fascination more than solemn explanations about context and codicology (even if, in the end, these offer more sustaining nourishment).

‘Doctor dog treating sick cat, 15th century’ – detail of folio 25v of manuscript with shelfmark Db. 3.20, unknown artist. Edinburgh University Library

The publication of Weird Medieval Guys in November came a few days after the cyber-attack on the British Library that has taken down its website – and with it, all of the catalogues and digitised manuscripts on which this book and its associated social media feeds have been heavily reliant. Disruption to the British Library’s digital estate is anticipated for months to come. Meanwhile, the transformation of Twitter into X has resulted in a palpable diminution of engagement from the communities that once gathered there to share observations and questions about medieval manuscripts. These disruptions underscore the ephemeral nature of the digital medieval manuscript. A parchment manuscript can survive in extraordinarily good condition for more than a thousand years, but will its digital surrogate be available from one day to the next? From this perspective, the phenomenon of the social media account materialising as a printed book marks a fascinating shift that echoes first the late antique move from roll to codex, and the return to scrolling – this time on screen rather than on papyrus or parchment – from the mid 1990s. Are we witnessing the tide turning back from scroll to codex? Just as libraries around the world have come to rely on digital facsimiles as surrogates for medieval manuscripts, this publication gestures towards a time when we will depend on the printed book as evidence of an evanescent social media feed.

Weird Medieval Guys: How to Live, Laugh, Love (and Die) in Dark Times by Olivia Swarthout is published by Square Peg.

From manuscripts to memes, and back again

Detail from folio 184r of Beatus of Liébana's Commentaria in Apocalypsin (11th century), unknown artist. Photo: Zentralbibliothek, Zürich

Share

Since 2019, Olivia Swarthout has been sharing the raucous, racy, ridiculous images that proliferate on the leaves of medieval manuscripts with a huge social media audience. Juxtaposing images of monsters, miracles and the odd anthropomorphic vegetable with dry captions, @weirdmedieval on X (formerly Twitter) and @weirdmedievalguys on Instagram offer moments of astonishment and amusement amid a stream of catastrophes, outrages and cat memes. In doing so, they connect a vast number of viewers to the extraordinary digital resources that institutions have generated over the past 25 years or so: thousands of medieval manuscripts have been fully digitised and made freely available (for those with the skills and determination to find them) on institutional platforms around the world. These include many of the world’s largest collections, such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Vatican, the Bodleian and the British Library (but more on this last in a moment).

‘Worm getting drunk, France’ – detail of folio 302r of Hours of Charles the Noble, King of Navarre (c. 1405), Master of the Brussels Initials and Associates. Cleveland Museum of Art

Weird Medieval Guys: How to Live, Laugh, Love (and Die) in Dark Times translates the social media experience into book form. The subtitle alludes to the rhyming of medieval and modern calamities (war, pestilence, famine, death) and to the didactic underpinnings of many of the images that appear in manuscripts. Even the silliest images (rabbits flaying a man; an owl bishop surrounded by apes) turn out to have roots in biblical texts and in the exemplary stories with which medieval preachers salted their sermons, as Lilian Randall demonstrated in her landmark study Images in the Margins of Gothic Manuscripts (1966).

The book is organised thematically, with Part 1 focused on images and wry commentary about life, love and death. Part 2 mines the bestiary for bats, hedgehogs, mermaids and bees, with captions that combine amusingly direct descriptions (‘Boar wearing pants’) with affectionate mockery (schematically-drawn bees are ‘sweet little peanuts, flying off to their well-endowed hive’). These sections are framed by images of the Creation at the start, and the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse at the end.

‘Sweet little peanuts, flying off to their well-endowed hive’ – detail from folio 64v of Anonymi tractatus de quadrupedibus, de avibus et de piscibus (1301–1400), unknown artist. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Richly illustrated and lightly written, this book will amuse its readers, but it will be up to them to discover more about the contexts in which these images were made. A list of photo credits at the end gives the institution, shelf-mark and folio reference for each of the images, but otherwise information that might enable the curious reader to dig deeper (dates, places of production, links to the digitised manuscript, notes on further reading) is absent, signalling that this a book for the humour shelf, not the (art) history reading list. This is an observation, not a complaint: such publications play a valuable part in the art-history ecosystem, drawing new voices, perspectives and audiences to material that is otherwise largely the preserve of specialists and their students. And who wants to be a vibe-killing bibliographer-art historian, popping up in the feed with facts and corrections? In its way, Weird Medieval Guys follows the tradition established by medieval preachers and artists themselves: laughter, wonder and a little shock now and then can spark fascination more than solemn explanations about context and codicology (even if, in the end, these offer more sustaining nourishment).

‘Doctor dog treating sick cat, 15th century’ – detail of folio 25v of manuscript with shelfmark Db. 3.20, unknown artist. Edinburgh University Library

The publication of Weird Medieval Guys in November came a few days after the cyber-attack on the British Library that has taken down its website – and with it, all of the catalogues and digitised manuscripts on which this book and its associated social media feeds have been heavily reliant. Disruption to the British Library’s digital estate is anticipated for months to come. Meanwhile, the transformation of Twitter into X has resulted in a palpable diminution of engagement from the communities that once gathered there to share observations and questions about medieval manuscripts. These disruptions underscore the ephemeral nature of the digital medieval manuscript. A parchment manuscript can survive in extraordinarily good condition for more than a thousand years, but will its digital surrogate be available from one day to the next? From this perspective, the phenomenon of the social media account materialising as a printed book marks a fascinating shift that echoes first the late antique move from roll to codex, and the return to scrolling – this time on screen rather than on papyrus or parchment – from the mid 1990s. Are we witnessing the tide turning back from scroll to codex? Just as libraries around the world have come to rely on digital facsimiles as surrogates for medieval manuscripts, this publication gestures towards a time when we will depend on the printed book as evidence of an evanescent social media feed.

Weird Medieval Guys: How to Live, Laugh, Love (and Die) in Dark Times by Olivia Swarthout is published by Square Peg.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The Musée de Cluny brings the Middle Ages bang up to date

The museum has sensitively reimagined all its displays to breathe new life into its medieval masterpieces

Mobs, murder and manuscripts – why ‘Pentiment’ is a must-play for art historians

In Obsidian’s new video game, you are a 16th-century Bavarian painter – but progress on your masterpiece is interrupted by parochial violence

The finest hours of Catherine of Cleves

Diane Wolfthal discusses the dizzying visions of heaven and hell to be found in a medieval prayer book at the Morgan Library